For most Westerners, who have the luxury of rhetorical objectivity while pondering the benign creep of tiny tanks across a television screen, the word “war” has been sanitized, denuded of the visceral horror and fear it is meant to evoke. It’s a word that’s been used too often and in too distant a context. It’s a concept that no longer holds its edge.

According to Croatian novelist and journalist Slavenka Drakulic, the word war “has recently become tamed and domesticated in our vocabulary like a domestic animal, almost a pet.” So it goes without saying that one simply cannot grasp the possibility of war entering one’s daily life on a mild Sunday afternoon, say, while drinking Cabernet and eating pasta for lunch with a friend.

But war entered Drakulic’s life in just such an inconceivable way in the fall of 1991: She held her fork poised halfway between her plate and her mouth as low-flying MIGs suddenly roared over her apartment building in Zagreb.

The Western world’s reaction to the outbreak of war in the Balkans in the 1990s betrayed this lack of understanding of war as much as it betrayed a yawning gap in sensitivity to the fearful citizens of the Balkan nations, most of whom, despite the oft-repeated myths of their “ancient legacy of hatred and bloodshed,” were simply stunned by the presence of war in their own villages and neighborhoods.

One doesn’t live one’s daily life by the myths of ancient legacies; one lives by wondering, as does Drakulic’s schoolteacher narrator in “S., A Novel About the Balkans,” how one will manage to grade the progress of schoolchildren whose parents are fleeing the area. War, when it comes, comes as a shock, whether or not you’ve been born into a bloody legacy.

In her novel about the Balkan war, Drakulic makes S.’s initiation into the daily life of war as mind-bogglingly surreal as her own had been: S. is so taken aback by the sudden appearance of the young Serbian soldier who has just kicked in her apartment door that she invites him to sit down for coffee and then joins him, benumbed, at the table.

What follows for S. is a nightmare of monumental proportions — after being rounded up with all of the other Bosnian Muslim villagers in the town, S. watches as soldiers lead the village’s men away and listens, together with the other women and children, as gunshots ring out from a distance. The women are then taken to a warehouse where they are robbed, imprisoned, forced to sleep en masse on the bare concrete floor, to defecate as a group in an open field and to watch, again in silent helplessness, as their young girls are led away by guards. S., too, is soon led away to the “women’s room,” where the youngest and most attractive women are sequestered so that they can be repeatedly raped, beaten and tortured at the whim of Serbian soldiers.

The real nightmare, though, is that the character of S. is the only fictional element in Drakulic’s novel. Everything that happens to S., all that she experiences and witnesses — from her months in the women’s room to the horrible realization that she’s become pregnant, from observing another rape victim calmly smothering her newborn with a pillow to hearing that guards are forcing Muslim fathers to rape their own sons or be shot — comes from interviews with women who were victims of acts of breathtaking cruelty and racial hatred.

“War is merely a general term,” thinks S. from the Serbian prison camp, “a collective noun for so many individual stories.” Drakulic’s “S.” is the true story of the women who learned the real, unspeakable meaning of war in the Balkans.

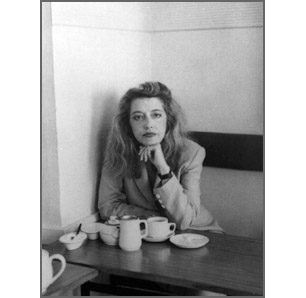

Drakulic has been observing and recording the everyday experience of life — politicized, random, gruesome, hauntingly enigmatic — in her part of the world with acuity and insight throughout her career as a respected writer and journalist. Her concern for the lives of women is long-standing: She is a founding member of the first network of Eastern European women’s groups and has served on the advisory board for Ms. magazine.

In addition to the major European newspapers for which she writes regularly (Italy’s La Stampa, Germany’s Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Sweden’s Dagens Nyheter), Drakulic is now a contributing writer to the Nation. She’s the author of “The Balkan Express: Fragments From the Other Side of the War” and “Cafe Europa: Life After Communism.” “S.” is her third novel. Mothers Who Think spoke with her about “S.” and the terrible legacy of the Balkan war on the same day that the New York Times reported on the dismal conditions for women and children now swamping the Chechen refugee camps.

How did you come to be involved in documenting the war in the Balkans, and in particular, the experience of women during the war?

I was just there. I was born in Croatia — Yugoslavia — and all my life lived there. So, when the war started, it was my natural reaction — the reaction of a journalist and a writer to articulate events. These events, or the war, were so terrifying and changed people around me so much, that I felt compelled to describe that in order to try to understand what war does to people … to myself as well. And I am a woman. So I decided that these were the stories I wanted to tell. The war stories are about destruction and battles and number of killed and heroism, rarely about a woman or women.

You set out to write a nonfiction account of the “women’s rooms,” the experience of rape in the prison camps, but then chose the genre of fiction and created a fictional “everywoman” instead to tell this story. How did that decision come about? Were the Muslim cultural stigma of rape or the desire to protect the identity of the victims factors in your decision?

Rape is an incredibly strong cultural stigma in the patriarchal Muslim culture. And of course the identity of victims should be protected, but these concerns weren’t my real problem.

In 1992 I wanted to do a book of documents, of witness accounts of the victims of rape, with my introduction. That was my original idea. But the more witnessing I heard or read, the less I was convinced that they would work for the reader of such a book. The way stories were told — they were similar, repetitive and very … poor, limited somehow. So the effect was not one of identification, but of boredom.

In short, I realized that the terrible human drama was not fully present in the witness accounts. And I wanted people to listen, not to simply skip it. The only solution was to tell the story of a fictional woman, and through her all these stories.

What was the post-war experience of women who were defiled in the camps? How were they treated by their families and communities?

This is hard to say. There is no systematic evidence. Generally, the women do not talk about rape; they try to hide it. There are very few of them who come out in public and use their names. But there is a lot of anonymous witnessing.

Just recently one such book of witnessing accounts was published by CID, the Center for Investigation and Documentation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Witnesses’ identity was protected, of course. But what is distressing is that those women, or men, who were camp inmates do not have even the minimum of legal rights or means of recourse. By publishing that book they are trying to fight for their rights.

Is the experience of S. a typical experience? How much of what happened to her and what she observed — being moved to the women’s room, being beaten and tortured, becoming pregnant, observing other women killing their babies or committing suicide — comes from factual or anecdotal evidence collected during your research?

My character, S., is fictional, but everything that happens to her is true. Every detail comes from someone’s witnessing. Unfortunately. And how typical? Well, that is hard to say. I read that 80 percent of the imprisoned women were raped in the camps. There were about 600 camps with over 200,000 prisoners, of which 38,000 died or were killed. But what can you say about statistics, if for example one women was raped over a hundred times? Statistics don’t take this kind of fact into account.

Could you describe the nature of the research you did with the Center for War Crimes? How many women did you interview, and were most Muslim? How comfortable did they feel telling their stories?

Well, my research went on through years …

I first met some of these women in the late autumn of 1992 in refugee camps in Zagreb and Karlovac. They were mostly Bosnians, Muslims, but some were Croats as well. Then I dropped the whole idea, as I described. Then I read more witnessing, books, talked to more women … It was a long and painful process for me. For them, well, it was difficult to get stories out of them. They were very, very uncomfortable talking about it.

Later in my process as a writer I read a number of books on the psychology of victims and understood why they do not want to, and cannot, talk. No victim of any kind of trauma can speak. When they can begin to articulate their trauma, it means that they are recovering. I understood, then, why the witnessing of these women had seemed so reduced and repetitious.

Are there any other statistics regarding the experience of women in the camps? Does anyone know how many were tortured or killed? How common were the women’s rooms?

Several independent international commissions established that the number of raped women is 20,000 to 60,000. The Bosnian Ministry of Interior is declaring 50,000. Now, this is just an approximation, it serves as orientation. But in reality, it is very difficult to establish the exact number, because during the war and after it is difficult to compile any kind of statistics.

In order for any of these numbers to make sense, how many people were killed or how many children wounded, you need to have all of the relevant demographic parameters. And with refugees, that is nearly impossible. But it is fair to say that women’s rooms were a mass practice. More than that, women’s rooms were a systematic practice, an integral part of ethnic cleansing. It means that this method was used to scare a population off of the specific territory. There were many women’s rooms.

What has happened to the “rape babies”? Is S.’s experience of giving her baby up for adoption a typical one? Are some of those babies being raised by their mothers? What is the social status of those children?

In your book, a character recalls being told by the soldiers raping her “that she would give birth to their Serbian child and that they would force all of these Muslim women to give birth to Serbian children. Where are those soldiers now? If children are born, they will be born to these women and they, not their unknown fathers, will decide their fate.”

Not much is known about the babies, though there were probably hundreds to thousands. They have been protected from the very beginning. I heard that most have been given up for adoption. There are only a few examples of women who kept those children. However, their status is presumably not different from other children’s, since no one knows that they were conceived by rape.

What is the agenda of the Center for War Crimes for these women, beyond documentation?

There is none.

What are the lives of the women like now? I’m reminded of what S. thinks as she’s readying to leave the Zagreb refugee camp: “Wherever they wind up, all these people will reek of the past.”

Last year I attended the weekly meetings of a psychotherapist and about 50 such women. They are refugees in Berlin. They are trying hard to survive, to go on. It is an immense, everyday struggle. To me, an outsider, it looked as if they live two parallel lives: one on the surface, in the present, and the other, the invisible one, in the past. If they manage to live a little bit more in the present, it is already a success.

Do you think, as Varlam Shalamov says in the quote you use to open the novel, that “a human being survives by his ability to forget”? What does that say about our chances, as members of the human race, of escaping more horrors like the Balkan wars?

We all like to believe that we are good, that human beings are essentially good and that it is possible to escape horrors. But I am not so sure. I think we are both, good and bad, and it is only an illusion that we know ourselves and that we can predict how we are going to behave in an extreme situation like a war. We don’t know, we can’t guarantee for ourselves and I think this is the terrible lesson that war teaches you. On the other hand, if we can’t forget horrors that happened to us, we cannot continue to live. I believe Shalamov. He knew what he was saying, he was a prisoner in Kolima, the worst Siberian camp …

When you made the decision to fictionalize this story, did you feel any concern about the possibility that fictionalizing these unspeakable crimes could further distance us from them and from the women who were victims? Or that creating one “everywoman” could render the real victims more faceless — rob them of their stories, when our inclination as readers and news-watchers is to want as much distance as possible?

No, I did not. On the contrary, I realized that the only way for readers to identify with such suffering was to fictionalize a character, although not a story. Simply, there was no one woman who could tell her story in such detail, psychological and emotional. Victimized women can’t do that. It means that either their stories will stay in the domain of witnessing and thus remain inaccessible to the public or that the public will have to wait another 10, 20 or more years until one of the victims decides to write her memoir. But then she also has to be very talented. I am sure that will happen. In the meantime, I decided to write a novel.