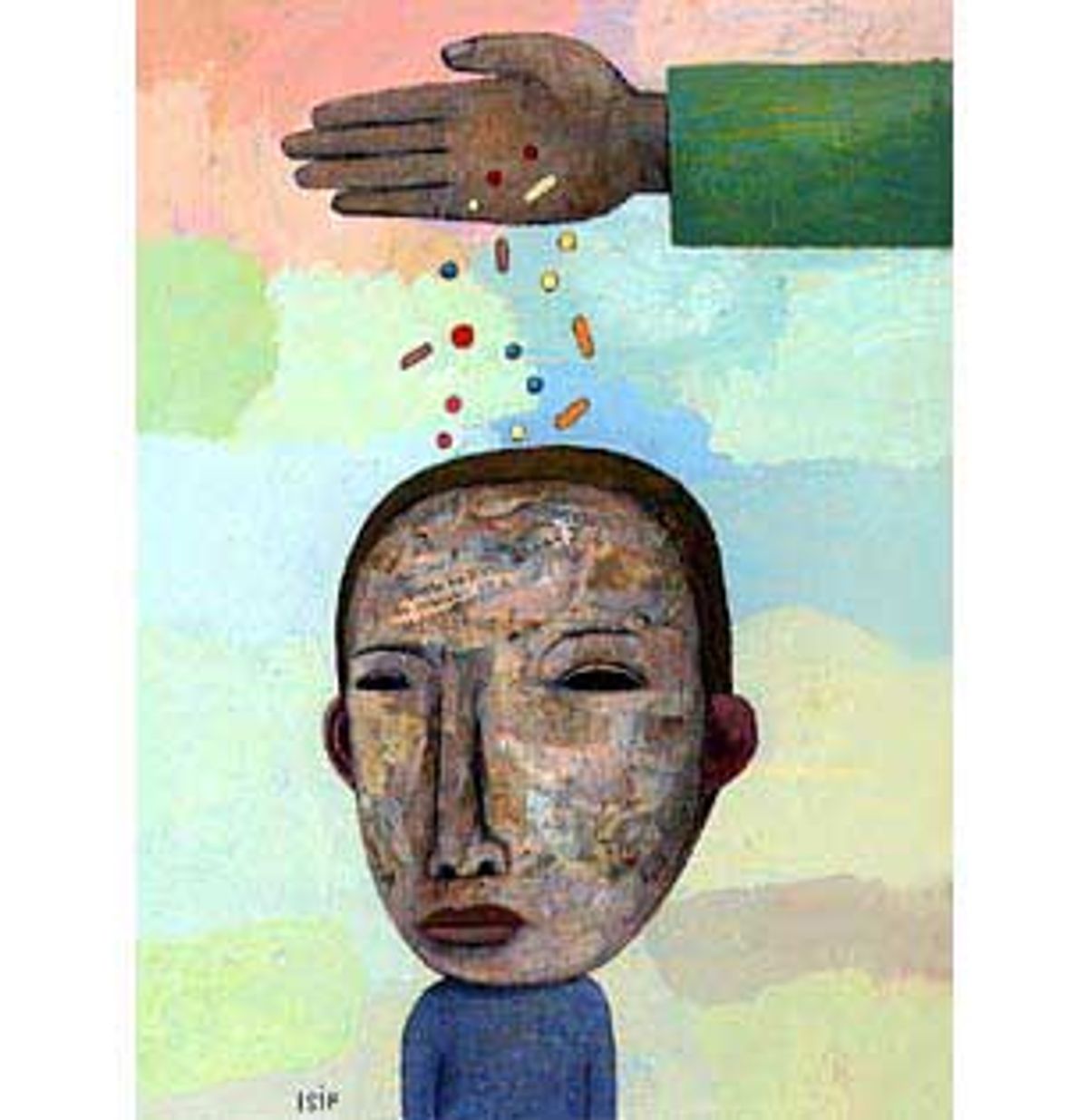

I've practiced behavioral pediatrics since 1978 in Walnut Creek, Calif., an affluent suburb of San Francisco. I have evaluated and treated more than 2,000 children who struggle with behavior and performance at home or at school. Last year alone, I wrote more than 400 prescriptions for Ritalin or a similar stimulant. I am not against prescribing psychiatric medication to children.

But I've become increasingly uneasy with the role I play and the readiness of families and doctors to medicate children.

I recently obtained some information from the National Disease and Therapeutic Index of IMS Health that adds to my uneasiness about the number of children taking psychiatric drugs in the United States.

IMS Health is to drug companies what the A.C. Nielsen company is to television networks. The pharmaceutical industry relies on it to report on the latest trends in medication usage. The company recently surveyed changes in doctors' use of psychiatric drugs on children between 1995 and 1999 and found stimulant drug use is up 23 percent; the use of Prozac-like drugs for children under 18 is up 74 percent; in the 7-12 age group it's up 151 percent; for kids 6 and under it's up a surprising 580 percent. For children under 18, the use of mood stabilizers other than lithium is up 40-fold, or 4,000 percent and the use of new antipsychotic medications such as Risperdal has grown nearly 300 percent.

Approximately 5 million American children take a psychiatric drug today. Based on production/use quotas maintained by the Drug Enforcement Administration and national physician practice surveys, it's possible to say with confidence that nearly 4 million children took the stimulant drug Ritalin, or its equivalent, in 1998.

Stimulants such as Ritalin have been used for more than 60 years to treat hyperactivity and inattentiveness in children. Over the past 10 years, however, psychiatric drug use for children has broadened considerably. There are more drugs and they are being used for more purposes. Ritalin is now prescribed for children as young as 2 and 3. A recent Michigan survey of Medicaid children found a few hundred toddlers taking stimulants and other psychiatric drugs. A study released two weeks ago in the Journal of the American Medical Association confirmed this trend in children of privately insured families.

Medicines originally developed and tested to treat depression in adults, such as the well-known Prozac (now in liquid form for easy pediatric administration), Paxil and Zoloft, but also Wellbutrin, Effexor and Serzone, are now being employed for a wide range of children's behavioral problems. Medications originally developed to treat blood pressure, such as clonidine (Catapress) and its longer-acting relative, Tenex, are also being used for behavioral management.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Pierre, 8-year-old Bobby's father, pleaded with me to evaluate his son. Bobby was on three different psychiatric medications. Pierre and Bobby's mother, Carol, had bitterly divorced and had been fighting since Bobby was 2. Bobby had had problems at school since kindergarten. Teachers described him as distractible, hyperactive, slow to learn and with few friends.

But his behavior at home, especially with his mother, posed the biggest headaches. He defied Carol and flew into violent rages, hitting and trying to bite her. Time outs were ineffective because he would either escape from his room or completely trash it.

Pierre admitted that he had seen this kind of behavior from Bobby only three or four times over the past three years. But at Carol's, Bobby had major temper tantrums at least weekly. Carol took Bobby to a child therapist when he was 4. The therapist thought Bobby might have "ADD" -- attention deficit disorder or, properly, ADHD (H for hyperactivity). She also thought he was depressed because of the divorce. Weekly play-therapy sessions for Bobby continued for three years and Carol sometimes got advice from the therapist on how to handle Bobby.

Pierre only met the therapist once. He acknowledged he'd never been a big fan of therapy and questioned its value. Carol had been a psychiatric patient for much of their 17-year marriage. She suffered from serious bouts of depression and took Prozac, the well-known antidepressant, and Ativan, a medication for anxiety much like Valium.

Bobby's pediatrician started him at age 5 on Ritalin, the best-known stimulant for ADHD, because the boy kept getting up from circle time and twice ran out of the classroom at school. Later he was switched to a very similar stimulant medication, Dexedrine. Bobby's acting out and impulsiveness continued, so Carol took him to a child psychiatrist who added the drug Wellbutrin to his regimen, thinking that Bobby's irritability might be a sign of depression. (Wellbutrin has been used primarily to treat depression in adults, but has also been employed for a variety of other problems from anorexia nervosa to stopping smoking.) The Wellbutrin did not make much of a difference and after two months was stopped.

Bobby's problem persisted. At Carol's his bedtime would begin at 8:30 and at 11 Bobby was still up, getting out of bed, pestering his mother for water or food and driving her "crazy." Another medication, Anafranil, was prescribed to help him fall asleep. (Anafranil was originally used in adult depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder, a condition of unwanted recurrent thoughts and compulsive behaviors like repetitive hand washing. But it often was too sedating for most people to tolerate.) Bobby fell asleep faster when he took this pill. Pierre, who in general had fewer problems with Bobby, only occasionally gave him this medication.

Bobby was 7 when Carol took him to a private psychiatric clinic well known for its controversial use of brain scans for psychiatric diagnosis and its liberal use of psychoactive medications. Bobby, now getting bigger, had stabbed another child with a pencil. No brain scan was done but the psychiatrist said that Bobby suffered from bipolar disorder, the current name for manic depression, and should take yet another drug. This fifth medication, Neurontin, originally approved as an anticonvulsant, more recently had been categorized felicitously as a "mood stabilizer." The psychiatrist said this medication would help Bobby control his episodes of rage and prevent a further worsening of his symptoms.

When I first met Bobby he took Dexedrine in the morning, Neurontin three times a day and Anafranil at night only before bedtime. He took 12 pills a day when he stayed with his mother. At his father's, he usually skipped the Dexedrine and Anafranil, especially on weekends. Pierre was afraid to stop the Neurontin because he had been told that Bobby might experience headache and irritability if that medication were abruptly discontinued.

Bobby was a very unhappy, angry boy caught in a web of strained emotions and loyalties between his parents. He was not an easy child to raise, especially for his mother, who had her own problems with depression. Bobby's story is disturbing not for its uniqueness but for how it represents a growing trend in the U.S. -- young children are being given essentially untested and potentially dangerous psychotropic drugs alone and in combination in greater volume than ever before.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Diagnosing bipolar disorder in children as young as 3 has become the latest rage. It justifies using a host of meds to treat very difficult-to-manage, unhappy children. The old-line drug, lithium, has been replaced by newer, untested (in children) mood stabilizers like Neurontin or Depakote as a first-choice intervention for pediatric "manic depression." Finally, a new class of anti-psychotic medications -- the most popular these days is Risperdal -- is heralded as the ultimately effective treatment for a number of diagnoses whose common features are not hallucinations or psychosis, but severe acting-out behaviors.

No one knows precisely how many children are taking these non-stimulant medications. The most recent survey of physicians' practices had 1.5 million children taking an anti-depressant in 1996. Most were teenagers (girls are the majority), but more than 200,000 children under 12 are also prescribed an antidepressant. Other data tells us that rates of antidepressant use since 1996 continue to rise. For example, 150,000 prescriptions for clonidine were written for children in 1996. More than 100,000 children take "mood-stabilizing" drugs for purported bipolar disorder. Again, most are teens (here boys predominate) but it's being advised that children as young as 3 take these drugs. More than 200,000 children receive anti-psychotic medications, mostly to control unruly behavior rather than to treat hallucinations or other symptoms of schizophrenia.

The number of children combining two or more psychoactive drugs is unknown. Combined pharmacotherapy (known pejoratively as polypharmacy) has been strongly endorsed by leading research groups as the sensible approach to treating the co-morbid, or multiple occurring, diagnoses common in "high problem resistant behavior" children. Some doctors call it prescribing by "symptom chasing."

No other society prescribes psychoactive medications to children the way we do. We use 80 percent of the world's stimulants such as Ritalin. Only Canada comes close to our rates, using half, per capita, the amounts we do. Europe and industrialized Asia use one-10th of what we do. Psychiatrists in those countries are perplexed and worried about trends in America. The use of psychoactive drugs other than Ritalin for preteen children is virtually unheard of outside this country.

In my practice of behavioral pediatrics I regularly meet children under 13 on two psychiatric medications. A 5-year-old girl troubled by fears had tried eight different psychoactive drugs over the year before she saw me. I met the mother of a 29-month-old boy who wanted me to prescribe medication. I didn't, but later I learned the boy was getting lithium, Zoloft and Risperdal from another doctor.

Is this cutting-edge treatment or an outrage? I'm not sure. But with three or four exceptions, none of these drugs, alone or in combination, has been shown to be effective for a specific psychiatric condition in children. Outside of the stimulants and old-line anti-psychotic group, only two of the most frequently prescribed medications, Luvox and Zoloft, have been studied sufficiently to obtain the Food and Drug Administration's approval for psychiatric use in children. Only a handful more have been examined systematically to eliminate the placebo effect, which has a particularly powerful influence in psychiatric conditions and in children. None of the newer medications has been studied beyond a few months for efficacy or side effects, and no one has looked at their effects on children's growth and development.

Until recently the recondite and rarified worlds of academic child psychiatry and psychology have largely supported the increased use of these medications. Joseph Biederman, chief of Harvard's pediatric psychopharmacology clinic, hails the increased use of psychiatric drugs in children as evidence "that child psychiatry is finally catching up to adult psychiatry" in psychopharmacological practice.

Other leaders in the field of child psychiatry are not as sanguine. Michael Jellinek, who as the head of child psychiatry at Harvard is effectively Biederman's boss, and Peter Jensen, who recently stepped down as director of child and adolescent research of the National Institutes of Mental Health, have both publicly worried whether physicians' prescribing practices for children have outstripped their scientific substantiation. They are also concerned that not enough is being done about the world these troubled children live in.

It's Johnny's Brain: The Triumph of Biological Psychiatry in America

What makes America so different from the rest of the world in how it views and treats children's emotional and behavioral problems? Perhaps no other profession fell so completely under the sway of Freudian ideas as American psychiatry and psychology did in the first 60 years of the 20th century. Yet by the late 1960s critics both within and outside of American psychiatry had doubts about psychoanalysis as a science and as an effective treatment. In the 1950s drugs like lithium, Thorazine and Elavil, found to be useful in alleviating psychiatric symptoms, further challenged the Freudian hegemony on psychiatric thinking and practice in this country.

By the 1970s research and academic psychiatrists fomented an internal revolution culminating in 1980 with the publication of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III). The DSM III replaced the old Freudian diagnoses, which were based on traumatic childhood experience, with etiologically neutral lists of symptoms collected into supposedly definable syndromes. DSM III was meant only to be descriptive and used primarily for research. Few outside of an inner circle of research psychiatrists knew of a paragraph in the introduction, deleted at the last moment (ostensibly to maintain etiological neutrality), that said the presumptive cause of most of the disorders listed was biological, that is, the result of heredity or a chemical imbalance.

It really didn't matter what was written, because over the next 10 years American academic psychiatry shifted 180 degrees from blaming Johnny's mother for all his problems to blaming Johnny's brain and genes.

The introduction of Prozac in the late 1980s cemented America's belief in the biological basis for abnormal behavior. Prozac was no more effective than earlier antidepressants but had less severe side effects, which allowed greater numbers of less severely disabled people to continue to take the drug. A logic developed that if a drug improved behavior, the problems must be biologically based. No one speaks of headache as an "aspirin deficiency" even though the drug relieves the symptoms. Nevertheless terms like "chemical imbalance" became increasingly fashionable in explaining problem behavior.

Media exaggeration of scientific findings contributed to the revolution. The acceptance of Prozac made taking a psychotropic drug no longer taboo; it became the topic of dinner-party conversation. Nearly one in 10 Americans has taken Prozac or one of its close drug relatives. With so many adults taking a drug for mood, it didn't take long for the primary drug for children's behavior, Ritalin, to zoom in use.

Ritalin production and use for the treatment of ADHD rose by more than 700 percent between 1991 and 1998. Amphetamine production also used for ADHD initially lagged but has tripled in use since 1996. Trade amphetamine (primarily Adderall) surpassed trade Ritalin prescriptions in 1998, a testament primarily to the marketing success of the manufacturers of Adderall.

As Prozac opened the door for Ritalin use in children, Ritalin itself ushered in a new "better children through chemistry" age in our country. At least Ritalin had been the most studied of pediatric drugs, though only a handful of the thousands of studies look at patients other than boys or monitor the children beyond a couple of weeks. Meanwhile research on other psychotropic drugs for use in children has been limited. Until recently, funding for studies of psychiatric medication in children was meager by adult comparisons. Questions about children's rights and consent to participate in studies raised thorny ethical issues, and the pharmaceutical industry did not believe there was much of a market for these drugs in children and so it did not fund studies.

Ironically, the new belief in a robust market for psychotropics in children has fueled a host of pending studies of different drugs for different child psychiatric conditions.

The community of pediatric psychopharmacology researchers is rather small; Biederman's Harvard program has been arguably the most productive and influential. His work stands as prototypic of children's psychiatric research under the DSM (now in its fourth edition) and demonstrates how a drug becomes established in the pediatric psychiatric pharmacopea. His research has won awards and his professional publications are prolific.

Biederman's group demonstrated in the late 1980s that the tricyclic antidepressants (their chemical structure contains three "rings") imipramine and desipramine, abandoned as a treatment for childhood depression because studies had shown them to be ineffective, could be used in high doses to successfully treat children with ADHD who had failed to respond to stimulants. In 1996, the Harvard clinic published a paper that said that 23 percent of their ADHD children also "had" bipolar disorder. (Most child psychiatrists believed manic depression to be a rare disorder in children.)

The Harvard group had always found higher rates of co-occurrence or "co-morbidity" of other disorders in their ADHD patients, but this rate of bipolar disease in children astonished the world of academic child psychiatry.

Biederman further claimed he could diagnose manic depression in children as young as 3. Few of these children demonstrated the classic signs of mania, euphoria or grandiosity. They did not have distinct periods of several weeks or months between their highs and lows. These children could cycle on a daily basis. They were very angry, very irritable kids.

Few of these kids were crazy. They could distinguish reality as long as they weren't enraged. They were very unhappy and very difficult to control. But Biederman felt that children diagnosed as bipolar could be saved from a lifetime of antisocial behavior and substance abuse by aggressively treating them with medication.

The presumed hereditary and biochemical nature of bipolar disorder would justify the use of a new class of drugs known as mood stabilizers: lithium, Depakote, Neurontin -- all drugs with far more serious short- and long-term side effects than Ritalin.

The response from other academic researchers was mixed. Debate goes on in the professional journals over the definition and frequency of bipolar disorder in children. One psychiatrist commented cynically that "Ritalin is for irritable and irritating children while lithium is for very irritable and very irritating children." The practical effect, though, of the announcement of this new interpretation of pediatric bipolar disorder, was that these medications began to be used in very young children without even short-term evidence of their effectiveness and safety.

Of late, the new anti-psychotic drug, Risperdal, has been touted by the Biederman group as more effective than mood stabilizers in controlling the symptoms of bipolar children. Risperdal's ascendancy as the drug of choice has not been slowed by a different set of more serious disabling side effects.

How should drugs properly be studied for use in children? Only two of the newer psychotropic drugs have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of a psychiatric condition in children. Paxil and Luvox, both variations of Prozac, have proved effective in clinical trials required by the FDA for the treatment of pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). No other medication, as yet, has met FDA approval. Several drug trials in children, actively supported by the pharmaceutical industry, are under way.

Once a drug is approved for use by the FDA for the treatment of a specific medical condition, a doctor can legally prescribed it "off label" for any purpose. Virtually every other med used to treat children's behavior is prescribed this way. Off-label use of medicines in pediatrics is common, but nowhere more so than in psychiatric medications. Physicians are constrained only by their own judgment and ethics. Local hospital and medical boards usually do little to interfere with doctors' preferences for treatment.

Most of the drugs used to treat children's emotional problems first became available after they met the FDA's standards for approval in psychiatric clinical trials in adults. A few were initially approved for use in adults for other medical conditions: Depakote and Neurontin for control of seizures, clonidine for blood pressure.

The typical path to the widespread use of any of these drugs for children begins with a report of a single child's response to a drug, usually as a letter in one of the professional journals. Journal editors explicitly state their openness to these kinds of "case" reports and more critical peer review scrutiny is omitted. The report will generate other letters until a series of cases are reported in which everyone -- the kids, parents and doctors -- knows what drug the child is taking.

Such studies are notorious for creating expectations of both positive and unwanted placebo effects. In the only study demonstrating the effectiveness of Prozac in children when the patients and doctors didn't know which pill was taken, 60 percent of the improvement in depressive symptoms was attributed to the placebo effect.

The Super Bowl of drug testing, which supposedly can distinguish between the actual effects of the active ingredients of a medication and placebo, is called the double-blind randomized control study (DBRCS). In a DBRCS neither the family nor doctor knows whether the child is getting the medication or an identical capsule filled with an inert ingredient. Only the pharmacist who prepares the medication knows which capsule contains the drug to be tested.

Patients are carefully screened for the psychiatric condition to be treated and then are randomly selected to receive either the real drug or the placebo. The children are monitored by their parents and doctors for improvements and side effects; along with benefits coming from placebo, many children complain of unwanted effects like headache and stomachache while taking placebos. After a pre-determined period it is revealed who took the drug and who took the the placebo. Only then does one learn the "real" vs. "believed" effects of the drug.

Such DBRCS are expensive; until recently, pediatric psychopharmacology researchers have been limited by low funds for their studies. Those few DBRCSs that had been run usually included only enough children, usually fewer than 100, to generate the likelihood of a statistically significant difference between drug and placebo required for scientific journal publication, but not enough for FDA approval.

But with only scores of children assessed, drugs like Prozac, imipramine, clonidine and Wellbutrin have come to be prescribed for hundreds of thousands of children. Research with imipramine demonstrated that adult drug studies do not necessarily correspond to effects in children. Nonetheless, adult medication trials are regularly invoked to justify the use of those same agents in children.

Calls for increased funding for pediatric psychopharmacology research are ubiquitous within the child mental-health community. The pharmaceutical industry, which now sees a children's market large enough to justify the expense, is funding several large studies, hoping to obtain FDA approval for the tested drugs.

On the other hand, studies on psychosocial interventions provide no similar profit-driven initiative for investigation. The much lower funding for this kind of research comes primarily from government. However, with the profit-motive incentive to develop new drugs and the real-life pressures to medicate children these days, there is ever-increasing pressure to medicate.

When all you've got is a hammer, everything starts to look like a nail.

Shares