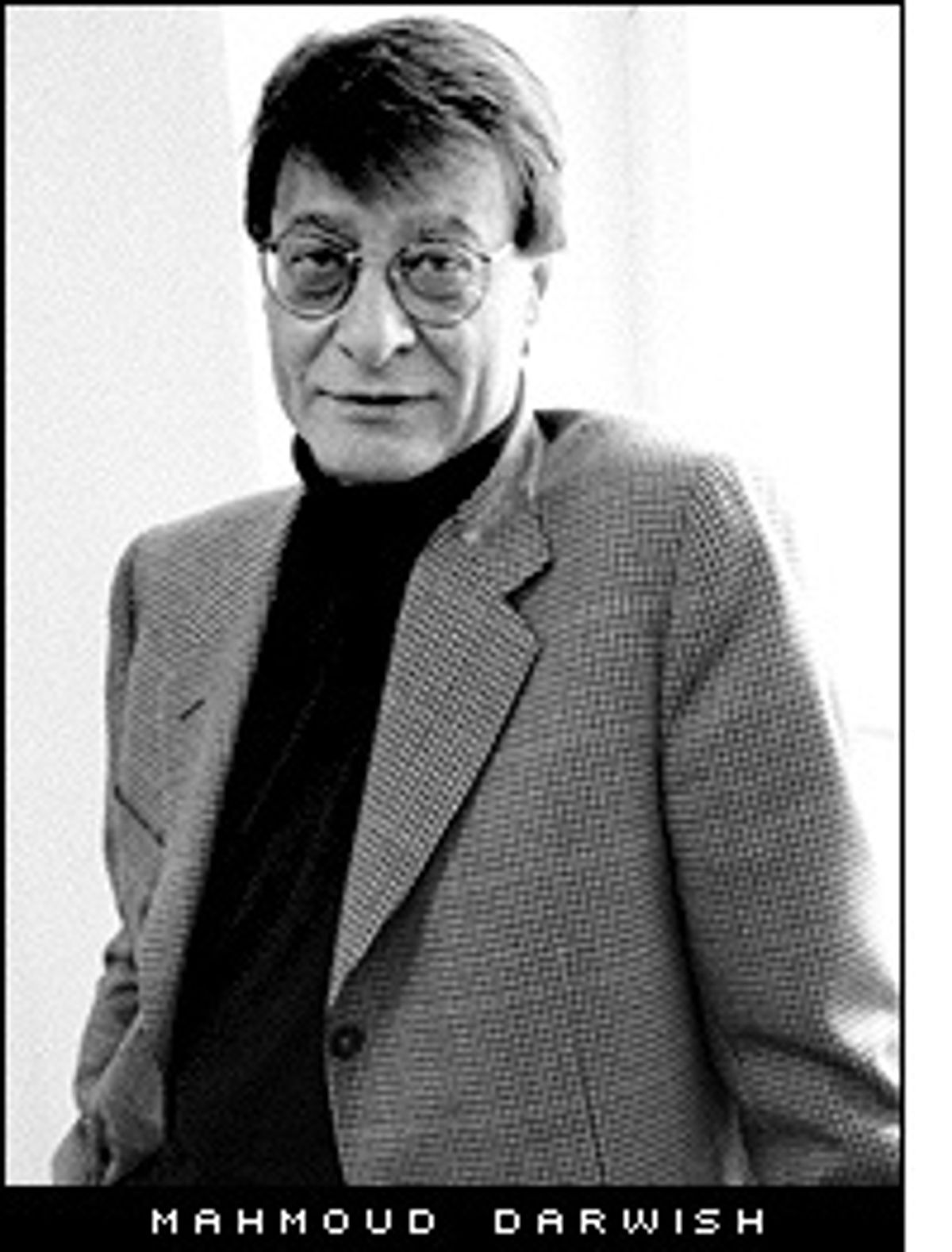

In his tweed jacket and tortoise-shell glasses, Mahmoud Darwish does not look like the threatening type. Sitting calmly in his immaculate office sipping coffee the other day, the world-acclaimed Palestinian poet talked about his search for new metaphors and his latest collection of love poems.

Yet Darwish, 58, unwittingly, sits in the eye of a political storm that is threatening Israel's government.

The storm erupted last week when Israel's iconoclastic education minister, Yossi Sarid, decided to add works by Darwish to the Israeli high school curriculum. What was conceived as a politically correct move to make the national curriculum reflect Israel's multicultural reality has become a political liability for Prime Minister Ehud Barak.

Struggling to keep together an unwieldy coalition and under intense attack from the right, Barak has publicly disavowed his minister and declared that Israel is "not ready" for Darwish.

In Israel's parliament, Darwish has been the subject of heated debates for the past few days. Right-wing politicians have been busy poring over the poet's prolific work looking for fresh ammunition. Quoting a line from a 1987 poem in which Darwish says "it is time for you to be gone," many accuse the poet of wanting to evict Jews from Israel. The brouhaha has caught Darwish by surprise. He took no part in the decision to alter the Israeli literature curriculum and has watched events unfold from afar. "I'm not a scandalist -- I don't like scandals," he said. "I'm well-enough known in my field and I don't want to be an obstacle to Israeli unity."

The fact that Darwish was once a high-ranking member of the Palestine Liberation Organization and one of the most eloquent voices supporting the Palestinian cause does not help. Darwish was born in the Galilee, now part of Israel, and his native village was razed by the Israeli army in the 1948 war. He was forced to live in exile for 26 years after he joined the PLO.

But Darwish has distanced himself from politics over the years. He refuses to believe that his lyrical poems pose a serious threat to Israel, the most powerful country in the Middle East. "The storm makes me believe Barak is right," Darwish said with a wink. "Israel is not ready to listen to the culture of others. Israelis do not recognize Palestinians as cultural producers. They accept us as obstacles, as part of the landscape but nothing beyond that," he said.

Education can become a political battleground anywhere in the world, but the row over Darwish reflects Israel's particular sensitivities. According to Israeli historian Tom Segev, the controversy is "a combination of coalition politics and a battle in an ongoing cultural war that is raging in this country."

On one level, the controversy is a matter of political infighting between liberals and conservatives. Shas, a religious party and key player in Barak's coalition, is using the quarrel to settle accounts with Sarid, the liberal education minister. Sarid has steadfastly refused to give his deputy minister, a member of Shas, control over the ultra-Orthodox Jewish school system. Shas has therefore decided to join its voice to the chorus denouncing Sarid's choice of poetry and is expected to vote against the government in a vote of no-confidence next week.

Sarid, a tad provocative, has refused to back down for the sake of the coalition. Fanning the flames of the religious party's anger, Sarid told the Knesset that he had drafted the new literature curriculum on a Saturday -- a desecration of the Sabbath, the Jewish day of rest. Sarid was once the author of a poem that read "I will die in the wrong battle." Segev predicts, "That's what is likely to happen to him."

On a deeper level, the controversy is a struggle over Israel's identity. "Geographically, Israelis are living in the Middle East, but culturally they don't want to be here," said Darwish. "It would benefit them to learn Arabic and open up to Arabic culture. But for the time being they want to be an island, part of Europe."

Although hundreds of thousands of Jews from Arab countries immigrated to Israel in the 1950s, and one-sixth of Israel's citizens are Arabs, most Israelis are raised in an environment that turns its back on Arabic culture. Students are more likely to read South American authors than the literature produced in neighboring countries such as Egypt or Lebanon. Part of Darwish's work has been translated into Hebrew, but few Israelis outside the left-wing intellectual elite have read him.

When Sarid chose pieces for the introduction to Arabic poetry, he was careful not to choose overly political poems.

He selected a poem by Darwish called "My mother" that contains little that can be construed as polemical. "Without your blessing/I am too weak to stand," Darwish wrote to the mother he was separated from by exile. "I am old/Give me back the star maps of childhood/So that I/Along with the swallows/Can chart the path/Back to your waiting nest."

It will be up to teachers to follow -- or not -- the minister's recommendations. But Sarid's attempt to open Israelis to Palestinian culture has been perceived by some as a frontal assault on Zionism, part of a trend to delegitimize the creation of Israel by lending an ear to the Palestinians. "They're against the principle, not the poem," said Darwish.

Despite his current lyrical focus, the poet remains a political symbol because of his history. Segev described him as "a kind of red flag" for the nationalist right. "He's a Palestinian symbol so naturally everyone jumps on the name. Everyone competes to be more patriotic."

In the 1960s and 1970s especially, Darwish's poetry focused on the themes of dispossession, exile and resistance to Israeli occupation. "Nothing of our ancestors remains in us, but we want/the country of our morning coffee," he wrote in one poem.

"I am the son/of simple words/I am the martyr of the map/the family apricot blossom," he wrote elsewhere. "Return to me my hands/Return to me/My identity."

Darwish resigned from the executive committee of the PLO in 1993 to mark his disapproval of the Oslo peace accords, which he considered a sellout of Palestinian aspirations.

That doesn't make him the "Jew-hater" that the Israeli right sees him to be. He claims his lines about ridding the land of Israelis or blowing up the conqueror's tanks with fig-tree branches refer to the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza -- not to the whole of Israel. He has friends and supporters in Israel, publishes Israeli poets in his literary review, Al-Karmel, and has no problem recognizing Israel's right to exist, he says.

For the past two decades Darwish has tried to distance himself from politics. After living in exile in Cairo, Beirut and Paris, Darwish was allowed to return home four years ago. Now living in Ramallah, a city north of Jerusalem under Palestinian control, Darwish says he feels free to write about things other than suitcases and his homeland because "when you have something, you talk less about it."

But, he adds, "I still live with exile in the heart."

Shares