If the people of Connecticut took over the state capitol, the media would swarm into Hartford and the nation would tune in to watch. Such a move might warrant the intervention of the FBI, the Justice Department and the National Guard. But for almost two months, 100 Indians have been occupying the tribal council headquarters here and the story has barely traveled past the edge of the plains. Despite the fact that a sovereign government is under siege, there has been a virtual news blackout.

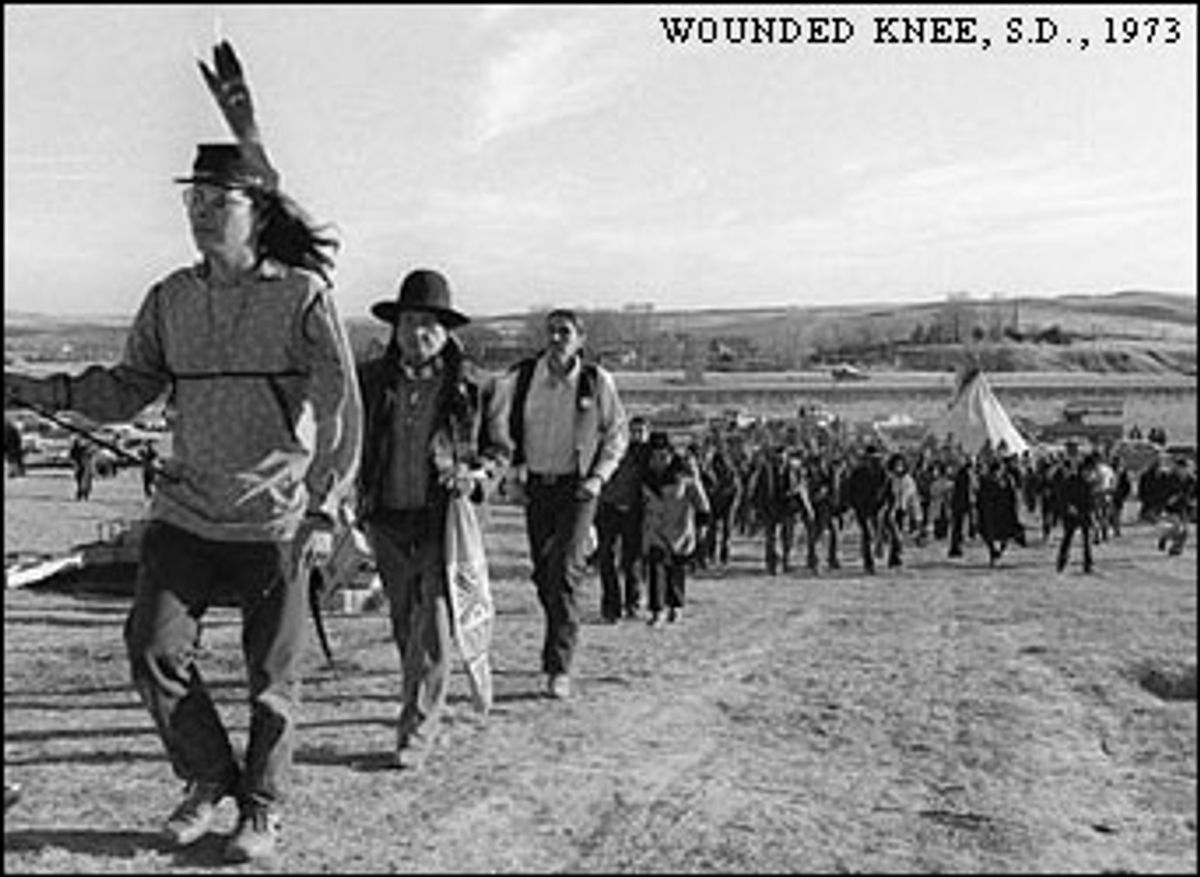

Jan. 16 a group calling itself the Grass Roots Oglala Lakota Oyate entered the Red Cloud Building and declared a takeover of tribal council headquarters. They met no resistance as they seized financial records and installed their own tokalas, or scouts, for security. They sealed off part of the building containing critical files, locked down the computers and called in the FBI to remove all financial records. That they summoned federal law enforcement was in sharp contrast to the famous Wounded Knee uprising of 1973 in which three people were killed.

This takeover, planned for nine months, was a desperate measure by a group who claim their tribal council has embezzled millions of dollars, that mismanagement of funds has forced the Oglala Sioux into the depths of poverty, and that they had no recourse but to sieze the seat of power.

Pine Ridge lies in the poorest county in America, with 75 percent unemployment and an average family income of $3,700 per year. The life expectancy for men is 48 years, 25 years below the national average. The infant mortality rate is the highest in the country. Bad health, disease, drugs and alcohol have ravaged the Oglala Sioux. Their culture has been diluted by television and their language is gradually dying out.

"Millions are being embezzled and nothing's being done," says Floyd Hand, one of the leaders of the Grass Roots movement. The group points to personal loans to councilmen as high as $126,000 in one month (despite a $500 cap), countless job placements made to council members' families and a complete disregard for the tribal constitution. The group has demanded the resignation of treasurer Wesley "Chuck" Jacobs and immediate suspension of all council members, pending a referendum vote. They are also calling for a complete overhaul of the current form of government. Hand insists that the only way to expose the truth is through a full forensic audit, and the only way to accomplish that was through a takeover.

Regardless of whether the takeover was justified, it seems to have broken years of stalemate. The occupation has forced the Bureau of Indian Affairs to intervene in what Robert Ecoffey, BIA superintendent for Pine Ridge, claims is an "internal matter," and an independent audit of the general fund is under way. Jacobs has been suspended pending a hearing. Other council members have been sent into a frenzy defending their actions, and Harold Dean Salway, tribal president, has been forced to document the spending of $30,000 in federal aid given in the wake of last year's devastating tornado.

While people on the reservation may disagree on the Grass Roots movement's methods, they agree that the tribe's funds are chronically mismanaged, that nepotism rules job placement and that a handful of people are getting rich while the rest of the tribe struggles to survive.

That's why the Grass Roots movement has attacked not only the individuals currently running the tribal council, but the entire tribal council system. Established in 1934 through the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), it represented the federal government's attempt to create a democratic system on the reservations. Unfortunately, it disregarded many tribal customs, such as the traditional council of elders, and didn't spell out an adequate system of accountability.

The constitution and bylaws, which most tribe members have never actually seen, are vague documents that don't spell out any policies or procedures, explains Jaime Arobba, the independent accountant hired by the BIA to audit the general fund. As a result, council members have been able to make direct loans to individuals without any system of checks and balances, let alone any means of collection.

"People know there is no tracking system for loans and they won't have to be paid back," says Arobba, whose findings are due this month. He plans to recommend that the tribe set up a revolving loan program with a general manager, a committee and a formal application process. "Otherwise, the general fund runs the risk of turning into a big slush fund," he says.

Arobba, who has conducted audits for every tribe in the Midwest as well as many around the country, insists that five years ago people should have been holding meetings and electing officials who shared their concerns, rather than allowing the situation to deteriorate to its current state.

The Oglala Sioux have been mired in corruption for decades, argues Floyd Hand. "We're in the same situation today as we were 27 years ago," he says, referring to the 71-day siege of 1973. That incident was precipitated by a tribal council so corrupt that AIM (the American Indian Movement) was called in and both sides were armed to the teeth. At that time, tribal council president Dick Wilson and his GOON Squad (GOON stood for Guardians of the Oglala Nation), were so out of control that Pine Ridge had the highest per capita murder rate in the country.

Thankfully, the atmosphere today is peaceful -- but that's probably part of the reason hardly anyone outside the reservation knows what's going on at Pine Ridge. The Grass Roots movement is committed to peaceful means. When I asked one young tokala if there were any weapons inside the Red Cloud Building, he answered somewhat indignantly, "We wouldn't have any weapons here; our peace pipe is inside." His respect for tradition lies at the heart of the Grass Roots movement.

When President Clinton gave his State of the Union speech in January it was the first time the name Pine Ridge had passed the presidential lips in that context in anyone's recollection. He mentioned his visit to the reservation, one of America's most depressed areas, and proposed a tax incentive for businesses that invest in such "new markets."

It would be laughable, if it weren't so tragic, that at the very moment Clinton was pledging his commitment to help the Lakota, their tribal council was under siege and no one in the federal government seemed to give a hoot. While Clinton talked about investment opportunities on the reservation, the tribal treasurer was only a horsehair away from a public lynching, and the tribal president was fending off impeachment proceedings.

People on the reservation love to joke about "Indian time." But by any measure, a six-week occupation is a relative eternity. "I don't see an end in sight," says Ecoffey, who hasn't set foot inside the Red Cloud Building in weeks. In the meantime, the tribal council continues to conduct business out of the basement of the Jimmy Mills Hall, while, across the street, home-cooked meals flow steadily into the tribal council's official headquarters, where the insurgents camp out in hallways and watch TV to pass the time.

Shares