In 1991, just two years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, confusion fell over the area formerly known as Yugoslavia. It was Babel revisited, as a nation found itself no longer able to speak the same tongue.

A famous photo shows Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito, for 35 years the nation’s mighty hunter, with his foot on the head of a freshly killed bear. Long after his death in 1980, one still finds it in bars and homes, framed above the TV.

For my friends Maple and Nicole, this is their text. On their own and together, the two aspiring academics have invested a great deal of time moving through it. They are excavating the remains of a monolith, and in many ways, it is the linchpin of their relationship. Since meeting two years ago in Zagreb, Croatia, they have co-written articles and lectured together on the subject of Balkan identity. While Nicole completes research for her Ph.D. dissertation, the two live in Ljubljana, Slovenia. On my way to Amsterdam to get an M.A. in cinema studies, I visit them. It is my intention to see what it is that they see in there.

A week into my tour, we drive to Mostar, Bosnia, for lunch. We get into the coupe that Maple and Nicole have rented for the trip, and drive over the mountains of the Croatian coast into Mostar’s valley. By now, I have adjusted to the windy one-lane highways and breakneck passing. Maple drives and I resign myself to the constructs of the guided tour. I am no longer the chief arbiter of my own well-being, but rather a passenger, a spectator situated to receive the data that enters my field. Nicole reads from “Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation” by Laura Silber and Allan Little, and like a good little moviegoer, I lap it up.

We cross the border into Bosnia-Herzegovina. Traffic stops at a guardhouse. Two soldiers sit under an umbrella at a table. A third, during short breaks in their conversation, peruses the papers of passing motorists. He takes our passports from Maple’s hand, doesn’t look at them and then hands them back to Maple.

That it feels more like a checkpoint than a border, I learn, is not accidental. Rather, nationalists in Croatia feel that, as most of those who live there claim Croatian heritage, southern Bosnia should rightfully belong to them. At stake here is much more than land. For nationalist Croatians, the border, in all its ripeness for overdetermination, marks where the Balkans begin.

Abandoning these brothers and sisters to Bosnian rule is to let them become Balkan, which is to let the family become Balkan, which is something akin to having a son marry the maid. For now, however, nearby United Nations troops make any attempt at military advancement impossible, and so the temporary border stands. The U.N., however, halts no commerce. We drive on and see Croatian banks and post offices.

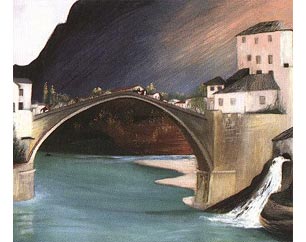

In both Serbian and Croatian, as well as the recently deceased language of Serbo-Croatian, the word “most” means bridge. The bridge of Mostar, built in 1566 on orders of the Turkish sultan, spanned the Neretva River. For hundreds of years, Mostar was the city of the bridge, a city that grew around it on both banks. Connecting Muslim, Orthodox and Catholic parts of the same city, the bridge symbolized the hopes for Bosnia: a nation of different ethnicities living out distinct traditions with mutual tolerance.

On Nov. 7, 1993, almost four years to the day after the dismantling of the Berlin Wall, the bridge of Mostar was bombed. Now Mostar is a mess. There are two cities on two sides of a river — one Croatian, the other Muslim. Despite the existence of other bridges, there is no contact between the two.

The mayor is a German diplomat. Troops from SFOR, the U.N.’s “multinational stabilization force,” police the streets. It is, by and large, a ghost town. In the beginning of the war, Croatians and Muslims formed an alliance against their Serbian aggressors. But as refugees of both ethnic groups flooded into Mostar, tensions rose until things finally erupted. For months Muslims and Croatians waged full-scale war in the streets while Serbs bombed them both from the outskirts.

We drive first through the Croatian side. I roll down the window and stare dumbly at what I guess one could call sights. For the most part they are nothing compared to what will come a few blocks later — pockmarks on facades from the shelling, a few buildings destroyed.

One building, a classic example of Eastern bloc aestheticless architecture, still stands. It takes up a small city block in the center of the Croatian side, like a hollowed and charred loaf of bread. We walk to Muslim Mostar. Comparatively, the damage on the Croatian side seems like acne. Here, whole neighborhoods are rubble. Through holes in the walls of one side of a building, I can see not only that the back of the building has been ground into its ingredients but that the building across the street has been destroyed as well. And it looks like this block after block.

I keep having the same thought: Here is a place where every code registers in the encyclopedia of news media. Because I don’t really know how to respond, I do like the news and look through the viewfinder of my camera. I snap shots. I try to capture the most Mostar can offer in a single image.

We eat lunch in view of the renovation of the bridge. While a Croat minister once boasted that, after the war, Croatia would build a better and older bridge, the job has been left to a Hungarian team. Using the original plans on loan from the Turkish government, they pull up each piece from the river below, and work to re-create the bridge exactly. We feast on grilled meats and watch adolescent boys swan-dive off the temporary span next to the construction.

There isn’t much to say. Nicole mentions that when she was here last, before the war, boys dove off the old bridge. Maple and I nod. We eat more grilled meat until there is no room for even thought. It is not the only time on this trip that I have found myself overcome with the urge not to think. Indeed, for me, the perversity of the situation here often negates the pleasures I might otherwise get from analyzing it.

Two days after the trip to Mostar, we drive through the Croatian Krijina, a mountainous region between Zagreb and the coast. Here we see the story of southern Bosnia transcribed onto a slightly different tableau. For generations, the majority of the population in the Croatian Krijina was Serbian. When Croatia declared itself independent from Yugoslavia, these Serbs wanted to remain under Serbian rule. The result was what we know as ethnic cleansing, where one army would eradicate entire villages of the other ethnicity. Nearly all of the Serbs in the Krijina are gone now. Those who weren’t murdered left. The few who remain are elderly, living out their days under persecution and the possibility of murder. Those who left were sent by Slobodan Milosevic to Serbian Kosovo, where again they were asked to fight for the Serbian fatherland. And now, following the most recent warring, they have been relocated again.

Nicole explains all this to me as we drive through sour weather. Rain slaps our windshield. Maple’s nerves seem torched by sudden stops on cheap, wet pavement and constant weaving through an endless string of traffic. When we break to relieve ourselves, Maple tells me not to stray too far from the road. “Land mines,” he says.

By this point, I miss my life and the movie watching that tends to structure it. The cinema offers a unique brand of privacy. As the reflections dance on the cave’s wall before us, we tune in and out. Our imaginations run along a band of incalculable frequencies, and no one else can perceive what we think or how we may or may not be feeling. By the end of the trip, I miss it. I suffer from withdrawals of mediated reality.

I find it difficult to understand why Maple and Nicole decided to study this area. I’ve seen enough and no longer want to understand the horrible things that have happened here. In a wine bar on an empty island — more former residents have moved to San Pedro, Calif., than remain — I made the mistake of mentioning my incomprehension of the “whole war thing.” Nicole sympathized, but Maple made no effort to conceal his disgust. As he sees it, and here I paraphrase with trepidation, pleading an inability to understand is to tacitly put yourself above those who fought, to exempt yourself from the possibility of ever acting the same way.

When former Secretary of State James Baker said, “We don’t have a dog in that fight,” about the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, he passed the same judgments Maple feels I pass. Baker and I agree: It’s a Balkan thing; we are too evolved to understand. What I lack in heart, or possibly will, to express is a vague sense that the opposite is not without its own pitfalls. Side effects and symptoms arise from the subject of who studies the area formerly known as Yugoslavia. Some time later, at a computer center in Amsterdam, the most progressive city on earth, I will fail again to make the argument. Indeed, I will find myself too cowardly to invoke the conceits of hardened souls and basic human benevolence that the argument requires.

But for now, we return to our trip. On my last day, we go for a hike in the Slovenian Alps. Maple and I, I think, look to each other for confirmation that the fabric of our friendship remains intact. We want my stay to end on a note of triumph. It works — Alpine air somehow breathes new life into our jangled nerves. For a minute it even allows me to transcend a certain kind of fatalism that, in the previous couple of days, had descended upon me. However, when we miss the trail that leads to the mountain lodge with the delicious gruel, I return to my pathetic sourness.

I see a great divide etched into the respective discourses of our studies. That I choose to study the movies and he this place, the various names for which invariably position their speaker into some ideological camp, begins to speak volumes to me. The movies, as theorists tell us time and again, are the locus of spectatorship and passive voyeurism. Poised at cliff’s edge, on a mountain trail, I see it oh-so-clearly: I watch this world with mesmerization and dread, while he, on the other hand, participates. And in so doing, he accepts all the complicity and dirty-handedness that action necessitates.

My theory feels confirmed on the drive back down the mountain. Maple uses the emergency brake to send the car fishtailing in a controlled skid around a couple of turns. Nicole tells him to cut it out, and I try to keep my mouth shut. But, during one particularly hairy turn, Nicole and I both freak out. Once the wheels regain their traction, Maple immediately realizes his error — that for those who have no control over the car, skidding on a mountain road can be a very unpleasant experience. But to me, in this Balkan moment, it’s too late. We exist at irreconcilable ends of a sliding scale of passive and active, observation and participation.

It’s not until I spend a couple of weeks in Amsterdam that my fatalism begins to fade. Humans are more pliable than their ideas. What had, against a landscape of war and destruction, seemed irreconcilable, begins to bleed together into the platitudes of taste. From the calm of my private life, with movies plotting their course through my veins like so much junk, I can safely see the differences between us as the spice of life.