"I am two fools, I know,/For loving, and for saying so/In whining poetry." -- John Donne, "The Triple Fool"

One hot summer night in 1962 in Bradenton, Fla., upstairs in a green wooden house on the Manatee River, I awoke from troubled sleep to find a chorus of voices taunting me. I lay in my bed and believed I was going to die. I was 9 years old.

I did not know what to do so I got out of bed and went into my parents' bedroom. My father was awake, sitting at the desk he had made of a hollow-core door laid across two filing cabinets. On the floor were stacked copies of the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings in which he had published an article about commanding an LCT (landing craft, tank) during a typhoon in the Pacific during World War II. He had his glasses on and was typing on his black, portable Royal typewriter on Manatee County School System letterhead. I went up to him and put my hand on his arm.

"I can't sleep," I said.

"Why not?"

"I keep hearing voices."

"What are they saying?"

"Nothing. They're just yelling."

He seemed to pause and think for a moment. "Well, why don't you try this," he said. "Just tell them to shut up."

My dad had a degree in psychology from the University of Chicago.

"What if they don't shut up?" I asked.

"Oh, I think they will."

"What if they try to hurt me?"

"They can't hurt you," he said. "They're just voices."

So I went back to bed and told the voices to shut up. To my surprise, they did. After a while I was able to go to sleep.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Thirty years later I was living in San Francisco and still hearing voices. They were not the psychotic auditory hallucinations of a madman. They were more like subvocal conversations running constantly, like rogue signals leaking into a radio transmission.

At times, of course, I wanted to hear voices; I was performing in a kind of abstract and jumbled, impressionistic spoken-word style at the time, and it helped to be able to unleash wholly irrational streams of verbiage like a madman. But I also felt threatened by this uncontrolled activity in my mind, and was seeking a way to find serenity in the midst of it.

I was also about to get married. I had led a complicated love life up to that point and I wanted wise counsel. On the advice of a former girlfriend, I went to see a Jungian therapist in an institute in a big, old converted Victorian house across from a hillside park.

The Jungian was a slight man of Indian descent, with skin of a deep copper color. He wore gray slacks and a light-blue, button-down shirt with a navy blazer. His hair was jet black and his eyes were steady. He had a little goatee. He sat behind a desk in a small, high-ceilinged office. His voice was kind but matter-of-fact. He asked if I had been in therapy before. I said no. He explained that what I told him would be confidential except if it appeared that I was a danger to myself or others, in which case he would be obliged by law to tell the police.

"Are you often anxious?" he asked.

"Yes," I said.

I explained to him that I was about to get married and I was fearful about two things: that I would be missing out on all the women who might await me if I stayed single, and that I was going to have to make a living and I was afraid that might interfere with my writing.

Then he asked, "Do you hear voices?"

"Of course," I said, a little defensively. "I'm a writer."

He looked at me without expression.

"Is that a problem?" I asked. He didn't seem impressed or amused.

"Let me ask you this," he said. "Do the voices tell you to do things?"

"Not really," I said. "I mean, sometimes they try to tell me to do things, but I don't obey. And sometimes they tell each other what to do. They're characters."

"So you hear multiple voices?"

"Sometimes."

"Do you remember when it began?"

"When I was 9," I said.

"And these voices -- do they ever tell you to harm yourself or others?"

"No," I said.

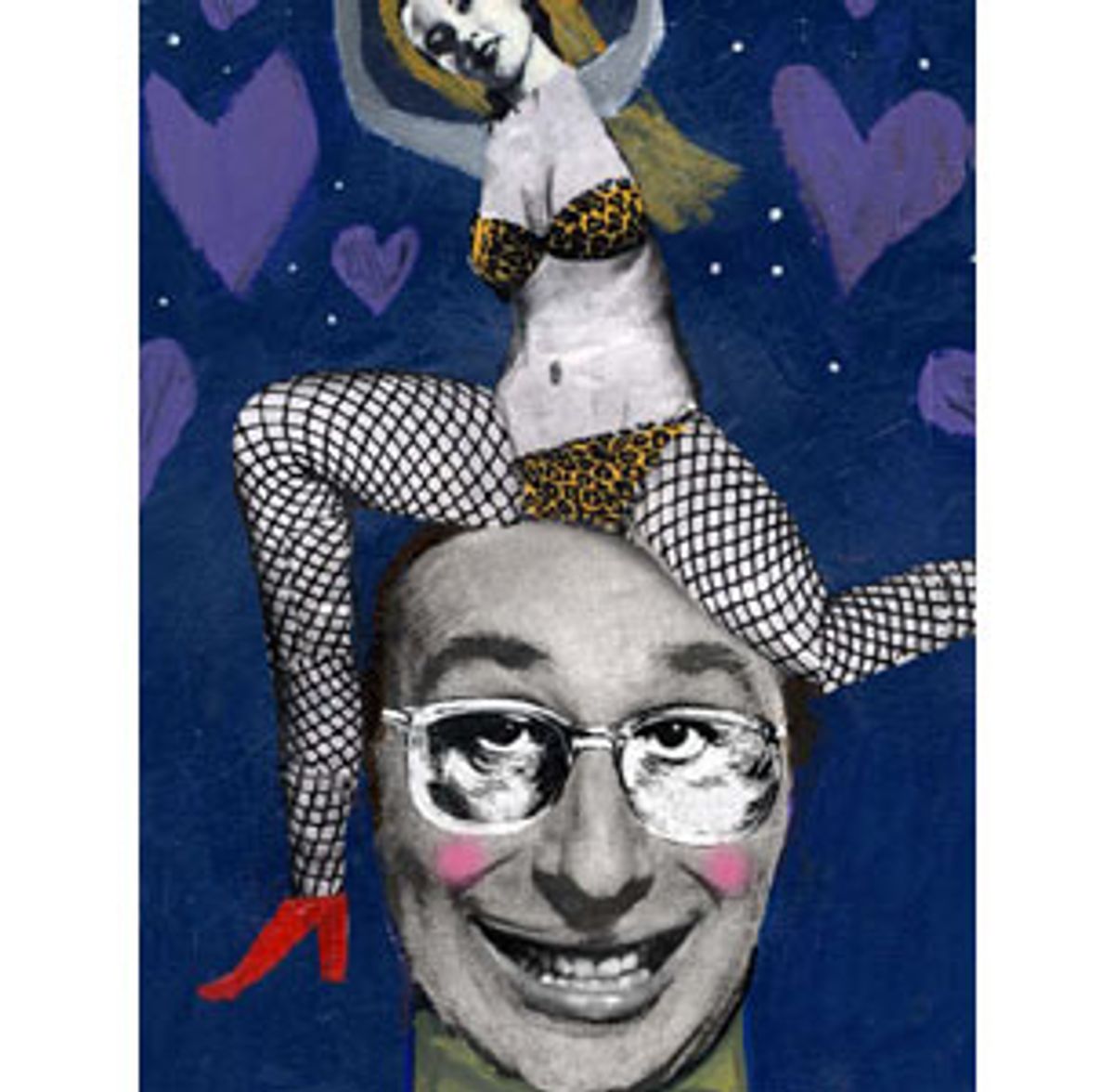

But I was lying. Because one voice was saying, "Strangle the little Jungian with the beard."

I have been married for six years now. I own a house in San Francisco. I have been faithful to my wife the whole time. But one rainy evening recently I was on my way home on the streetcar, and standing before me was a beautiful, young Asian woman with a small artist's portfolio. She wore black-and-white tennis shoes, tight jeans rolled up above her calf and a black sweater. She was slight of build and olive-skinned, with rich, dark-brown hair in a ponytail down her spine. I got off the train behind her and followed her to a church courtyard, where she faced me and pulled up her sweater and then turned around and, with her back to me, unzipped her jeans so I could reach around and put my hands on her hot skin. I was pulling down her panties from behind, slowly so they tightened over the crack of her ass and her hip bones and rolled with the friction of her skin over the tiny peach fuzz above the sacroiliac, and then, with a ballerina's precision ... She got off several stops back. It never happened. It's just my imagination, running away with me.

The voices have stopped for the most part, but my sexual fantasies go nonstop.

Like the voices in my head, my sexual fantasies began early. But they did not become a problem until I was married. Because when you're single, you know you can always try, however laughably out of your league you may be. But once you're married, unless you wish to live untruthfully, there's no chance. You've made your bed.

I met my wife under remarkable circumstances at a crucial time in my life. I had just quit drinking after undergoing the kind of sudden and dramatic spiritual experience that Alcoholics Anonymous co-founder Bill Wilson described in his 1939 book on the subject. I had pushed my divided self to the point of a radical fissure; into that fissure had streamed an unearthly light that saved me from madness. So I regarded my wife at the time, literally, as an angel. The world during those first few months was a luminous place of wonder. Years of deepening gray decline had given way magically to light and hope, the way color washes over an awakened world in the movie "Pleasantville."

During those months I came to view life in a whole new way, as a system of signs and symbols of the divine, as a procession of angelic interventions and coded messages, as, in a word, holy. So I gratefully took what I was offered. My wife seemed to have come to me like a gift. I have been faithful to her ever since, early in our relationship, I said, "I love you, but I'm still going to see other women," and she said, "No, you're not."

But having no good record of moderation in either women or drink, I had to endure an early period of conscious avoidance to succeed in abstinence. What I thought at first was jealousy on the part of my wife turned out to be just common sense: She didn't think it was a good idea for me to hang out with my former girlfriends. She was right. Who knows what would have happened. Likewise, I found out it was best to avoid bars, nightclubs, strip joints and the odd bachelor's tiki-decorated den equipped with hookah, aquarium and full bar.

This sudden shift in outlook occurred in April 1989. When I visited the Jungian in 1992, I was still seeking reassurance that I wasn't crazy. To my surprise, the Jungian refused to take me on as a client. I had always considered myself a fascinating psychological specimen any practitioner would be eager to examine. I asked the girlfriend who had recommended the Jungian to me what she thought. I told her what I had said to him about my voices. She said he was probably screening for psychosis. Psychosis! I'm a writer, I thought. And yet it was a lurking fear of deeper troubles that had driven me to seek help in the first place.

At any rate, a few months later I was able to enter a course of short-term cognitive therapy with a man who told me basically what my father had told me 30 years before: Talk back to the voices. He also suggested that I keep a daily record of my dysfunctional thoughts.

Much to my amazement, when I began to write down what the voices in my head were saying, it turned out they were saying crazy, ridiculous, hateful things. One was saying, "You can't write, you shithead." Another was calling me an asshole. A third was saying over and over, "It's useless. I can't do it. It's useless. I can't do it."

What was that all about? I had only been aware of the paralyzing fear and anxiety. I had never heard the actual words behind them. After a while, the voices quieted down, and through regular prayer and meditation I began to experience periods of exquisite serenity. That gave me a perch, as it were, from which to view the products of my imagination.

Unwanted sexual fantasies bring nagging doubts. Is this a sign I should act? Have I fallen into a bourgeois trap of monogamy? Is my true nature polygamous? Why else would I be having these thoughts and visions? If I have done the right thing by getting married, why do I continue to fantasize about women on the street, in elevators, on the streetcar, on airplanes, passing in cars, behind counters, in the park, at the mall?

It wasn't so much sexual fantasies themselves that caused anguish during this period as it was the doubt and fear they aroused. I felt hopeless because I knew that no matter how sharply I imagined that supermodel's perfect breasts, adorned by a gold necklace as she leaned over the railing of a bayside cafe, no matter how deliciously I could picture lifting her skirt and rolling down her panties and having my way with her, I'd never in reality get anywhere near her.

Nor, frankly, did I want to. I wanted just to imagine it. At times my fantasies seemed to threaten my relationship with my wife. What would she think if she knew what I thought? This was a great torment to me. My wife is the light of my life, the center of my earthly existence. Why would I doubt that?

I feared that even writing about these thoughts might damage our relationship. So I knew I had to talk to her. We were out with friends and I said I was going to write a piece for Salon about my fantasy life, and she said, "No, you're not!" A few weeks later I brought it up again when we were dining together and she appeared to have thought it over; perhaps she had accepted the fact that I was determined, and that I was acting in this matter strictly as a writer. She said I should give some thought to my future reputation. "Don't embarrass yourself," she said, "and don't write anything you'll regret."

I will not regret it if I can convey how I have come to be free of the nagging guilt that often accompanies sexual fantasies. One day I was walking along and saw an attractive woman, but instead of having that agonizing feeling of impossibility, I imagined that she and I were lovers already, that we had spent a passionate night together and now it was the next day, and I was simply admiring her. "God, she was fantastic last night!" I said to myself, and a light went off in my head. It's better to imagine having already had sex than it is to imagine its possibility! Why despair over what never will be, or live in fear that it might happen, when you can sigh and bask in the warm glow of recent love, as if it had already occurred?

The notion of thought as a precursor to action is embedded in our language: "Don't you even think about it!" But the opposite seems to be the case: If we really thought about it, we probably wouldn't do it. My generation was, of course, the generation that preached we must throw open the doors of perception and charge down the road of excess to the palace of wisdom. Central to the madness of the '60s was the belief in the holiness of willful stupidity. The courage to act without thinking, to leap without looking, was an affirmation of a faith in something larger than us.

In the '60s, our fathers' overarching faith in reason and force and their unwillingness to just go with the flow seemed to have driven them to a dry, barren place of slide rules in the Nevada desert that called up mushroom clouds of oblivion. Their logocentric arrogance seemed to threaten the world with destruction. We did not understand how their warlike spines had been molded in the furnace of war and then quenched to brittle hardness in the chill of the suburbs. We did not understand how their caution had been learned in a treacherous world; what we saw was a generation of overly serious men; we thought a little craziness would lead to knowledge of a higher order that included the irrational. Perhaps it did. But by overlooking the powerful and enduring values of our fathers, we also created a culture of insipid shallowness and paralyzing uncertainty. I don't think my period of debauchery and drunkenness was unrelated to the failure of my generation to adopt some of our fathers' hard-won lessons.

For four years now I have ridden the streetcar every day to and from work in downtown San Francisco. Women enter and leave the streetcar. They stand and sit and giggle and talk and bend over and adjust their skirts and pluck at their bra straps and put on lipstick and root in their bags and brush their hair and rest their weight first on one hip and then the other. They pull at their panties and adjust their dresses; they chew gum and pop candies into their mouths. They tie their shoes.

A yellow taxi roars by in the rain and I glimpse a brunet putting on red lipstick in the back seat with a compact mirror and I imagine a Nob Hill hotel room, the lights of Sausalito, a black garter and high heels, the smell of a certain jelly that comes in a tube, a bubbly drink ... I meet someone, shake her hand and imagine her on her back with her legs in the air and my mouth on her. There she is on all fours, her back arched, her head high, her eyes shining as she looks back at me. There she is hanging laundry in a backyard where the train tracks run. She's wearing a housedress, translucent in the low morning sun, and when she finishes we are going to go inside and she is going to get down on her knees ...

I get on the elevator and share it with a tall, round, balding man who's sipping coffee and headed for the fifth floor. As he leaves the elevator I give him a walloping kick in the butt and send him sprawling on the floor, his coffee splattered across the carpet, on his face a sputtering, wounded perplexity: What was that all about? It's just my imagination, running away with me.

There's something wild and magical going on. The ancient animal within us is dreaming while we pretend to be awake.

Shares