Rosette, when you ask, what do I say?

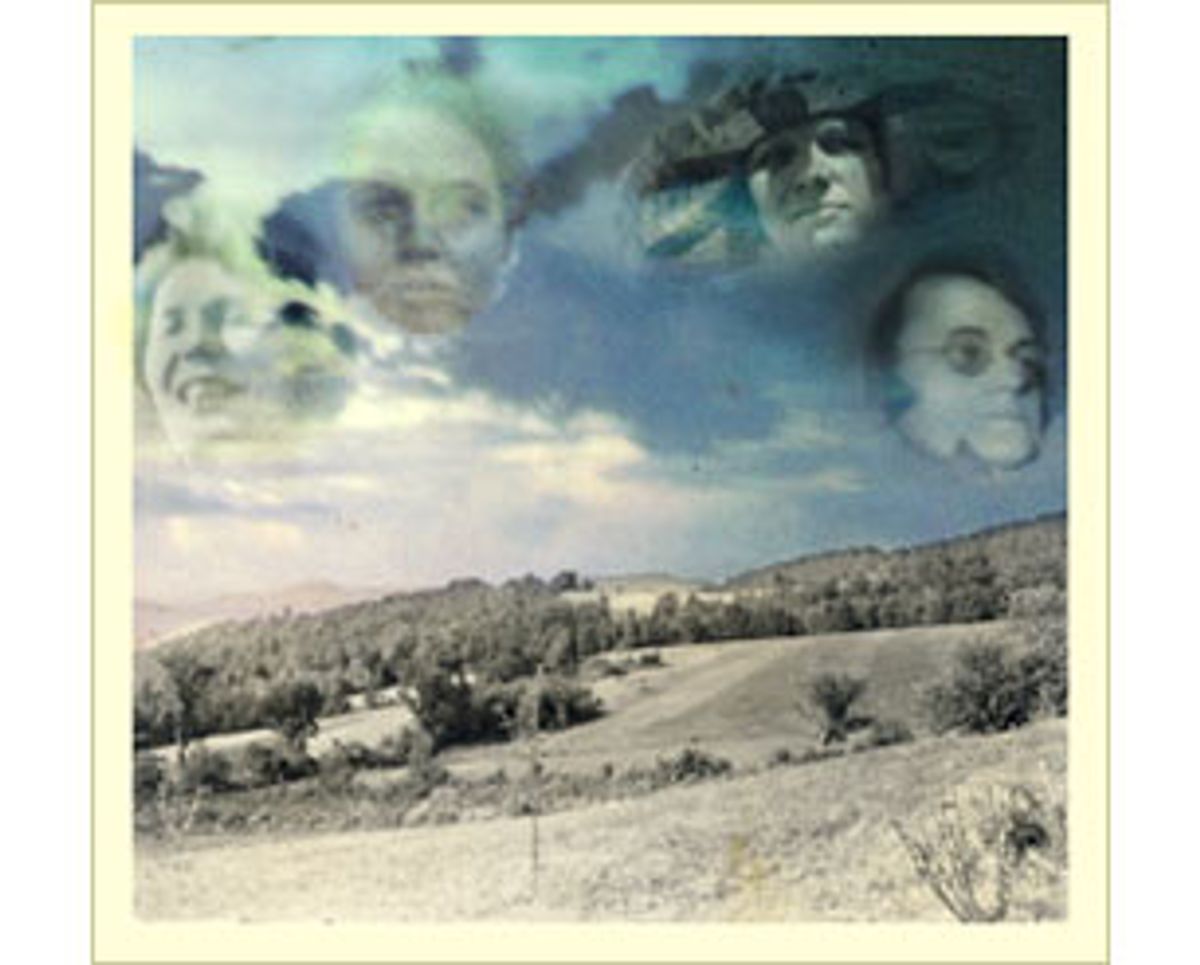

Do I say: Rosette, my baby girl, my third and last daughter, the one who looks least like me but sleeps curled into my side each night, hand twined in my hair, spine against mine, the only one who was never rocked by her grandmother Alberta but inherited her full cheeks and winged eyebrows and love for footwear, the one not old enough for piano lessons but who sits at the keys to play a lilting-sad repetitious tune before telling me: "That was for my Gramma Alberta that died before I was born and I never got to even meet her" -- do I say, I don't know much, but this is what I know about all your grandmothers?

Your father's grandmother's mother had no name. Her father, a Cherokee, disappeared when she was a child near Nashville and her mother died when she was 8 or 9. She was taken away from the empty house by a white family who, though this was 1870 or so, used her as a slave.

They named her Fine. She was beaten and denied food and clothing; she picked wild blackberries to survive. One day, searching for berries, she found a bullet by the side of the road. She thought it would be her salvation and revenge against the old woman who abused her most.

While chopping wood and being screamed at one day, she finally hurled it at the veiny pale temple hovering near her. She was astonished when the bullet had no effect, was mistaken for a flying wood chip, and earned her another beating.

She met a man when she was 13. She ran away with him, became pregnant and then was abandoned. She lived in a migrant-worker shack. She had three children this way, and then she made her way to Texas looking for her father, whom she never found. Another man took her into his farmhouse, where she had two more children. When he died, his land and property were stolen by neighboring whites, and she ended up in Tulsa, Okla., where her oldest daughter had moved. Her youngest daughter, Callie, was 16 when she met a man named General Sims. She married him and had six children, including your grandfather, General Sims II.

No one knows where your grandmother Alberta was born. Maybe Mississippi, maybe Arkansas, maybe Calexico, Calif. -- all places where her own mother had traveled to on her hard path west, while having four daughters. Alberta lived in our city, Riverside, all her life. She married General Sims shortly after her high school graduation. She had seven children, including your father.

When your older sisters were born, she loved to hold them, gently bite their cheeks, chew meat into softness they could swallow and rock them to sleep on her chest.

When I was pregnant with you, she died. You were born in August, the same month she was, and of all the kids, you look most like her. You look nothing like the grandmother you have.

My father's mother, Ruby Triboulet, died long before I was born. Her cruel, careless husband abandoned her with her four children for months at a time, and finally took her to live in the high mountains of Colorado, though he'd been warned this could kill her. When my father went to visit, handing her his first child (not me), she suffered a stroke or aneurysm, nearly dropping the baby. She was 50.

My father left my mother when I was 3. She married my stepfather, Grandpa John, but his parents were already deceased, too. And the grandmother I always wanted, the Alberta kind, had died long ago.

In Switzerland, when my mother was only 10 and her two brothers much younger, her soft-spoken, gentle mother died of cancer. All my life, my mother refused to talk about it. Only now has she told me, once, that her mother's body was laid out in the front room, as was done in Europe in 1944, and that her life was never the same. The nurse who had taken care of her mother was a stern, demanding woman named Rosa. She married my grandfather, and after they had their own girl, the whole family moved to Canada.

My mother's stepmother treated her in a scary fairy-tale way. Eventually, she tried to marry off my teenage mother to an older pig farmer (she refused), and when the family wound up in California, my mother was 17 and moved into a rooming house only a mile from here.

Rosa is the only grandmother I ever had. She is not the rocking kind. She has never called me, baked me cookies or kept me for a weekend. When I was a child, she and my grandfather retired and moved to a mobile home in a rural community 20 miles from us.

A few times a year, we visited them. Grandma Rosa made heavy, delicious Swiss dinners, inspected our scalps and lectured us about vegetables, and, then, while the grown-ups sat stiffly on the artificial-turf-covered porch, we kids ran across the street to the alfalfa field.

When I was older, she would take me around her garden, a series of raised beds surrounding the trailer. She grew kohlrabi, Swiss chard, radishes and rhubarb, and grapevines trained on wires all around. But after an hour or so, she would indicate that it was time for us to go.

When I married your father, my Swiss grandfather didn't seem to mind that my husband was a very tall brown-skinned man. In fact, after family dinners at my mother's, my 5-foot-4 grandfather would sidle over to 6-foot-4 Dwayne and whisper in his heavily accented English, "You could probably reach that schnapps they keep in the cabinet up there over the stove, eh, son?"

But maybe Grandmother Rosa didn't like it. Who knows? She saw your sisters once at Thanksgiving and then, for years, she didn't see anyone. But a few years ago, after my grandfather died at age 89, my mother started to visit her stepmother again, driving out to the same mobile home garnished with parsley and grapevines.

When I was pregnant with you, I knew your father wouldn't be around much longer. I sat in this same chair where I sit now, writing names on pieces of paper like I did for your sisters. Gaila is named for both your grandmothers -- Gail and Alberta. Delphine is named for a tall, lovely flower. And you -- I wanted you to be as beautiful and hardy and ever blooming as a rose. I tried out names: Rose was too old-fashioned, Rosita and Rosina and Rosie weren't right. Rosa was my step-grandmother's name, which might bother my mother.

Rosette. Small, delicate, unusual and French, for my mother's actual birthplace.

When my mother was pregnant, and I was 3, and my father left, she called Rosa, who said she had made her bed and now must lie in it. Rosa did not help her when the baby was born. She did not come to get me or rock anyone to sleep. I don't think your grandmother Gail has ever forgiven her.

Your grandmother Gail is very short, with blue eyes and straight brown hair. You are tall, with cascading black curls and clove-brown eyes. You see your grandmother two or three times a week. Every Tuesday, you go to her house while I work; she doesn't bite your cheeks, but she does puzzles with you, teaches you to make meatballs and knits you vivid sweaters.

I look at you sleeping beside me. You are part African, part Creek and Cherokee, part Irish, part French, part Swiss. You are wholly American. You will be 5 years old in the summer.

You will play the lilting-sad song again, and say to me somberly, "That was for my Grandma Alberta that I never got to see." Does she whisper in your ear, near your plump cheeks?

Last month, Grandma Rosa stunned us by asking your grandmother to bring you on a visit. Only you. She watched you wander among the vegetables, and she mentioned casually to her stepdaughter that Rosette had been her own mother's name. She had never told this to anyone in our family. Her mother was a farm wife who had 12 children and a hard existence, cultivating hilly slopes (the only kind in Switzerland) and raising dairy cows. Of all the children, only Rosa and her sister Anni, still in Switzerland, are still alive.

Do I say, "You are no blood relation to this woman, and I have no idea how this coincidence came about? And how is it that on that visit, when she took you around the garden, you knew so much about flowers and growing?"

When you were 2, you planted red Flanders poppies in our yard, and the tall blooms were so unusual everyone stopped to ask where they came from. "From me," you said proudly. You planted apricot trees from pits, and they grew. You pick fruit, like Fine, and you plant seeds, and you dream of Alberta, stare at her picture.

Recently you said to me, in the garden, "Stop picking at your hands, Mommy." My thumbs and palms have deep bleeding fissures from washing floors and clothes and dishes and girls' long hair. From trimming fruit trees and roses and stray threads from skirts.

Do I tell you about Fine, that I think of her hands, and Rosette of Switzerland's hands, and my own mother's hands, and do I tell you I wonder what your hands will look like when you have children, when I am a grandmother? I have told you many times that I will be the rocking and cooking kind. Will you pick berries in your own wild garden? Will you braid your daughter's hair and say about me, "Your Grandma Susan showed me how to plant roses ..."

Shares