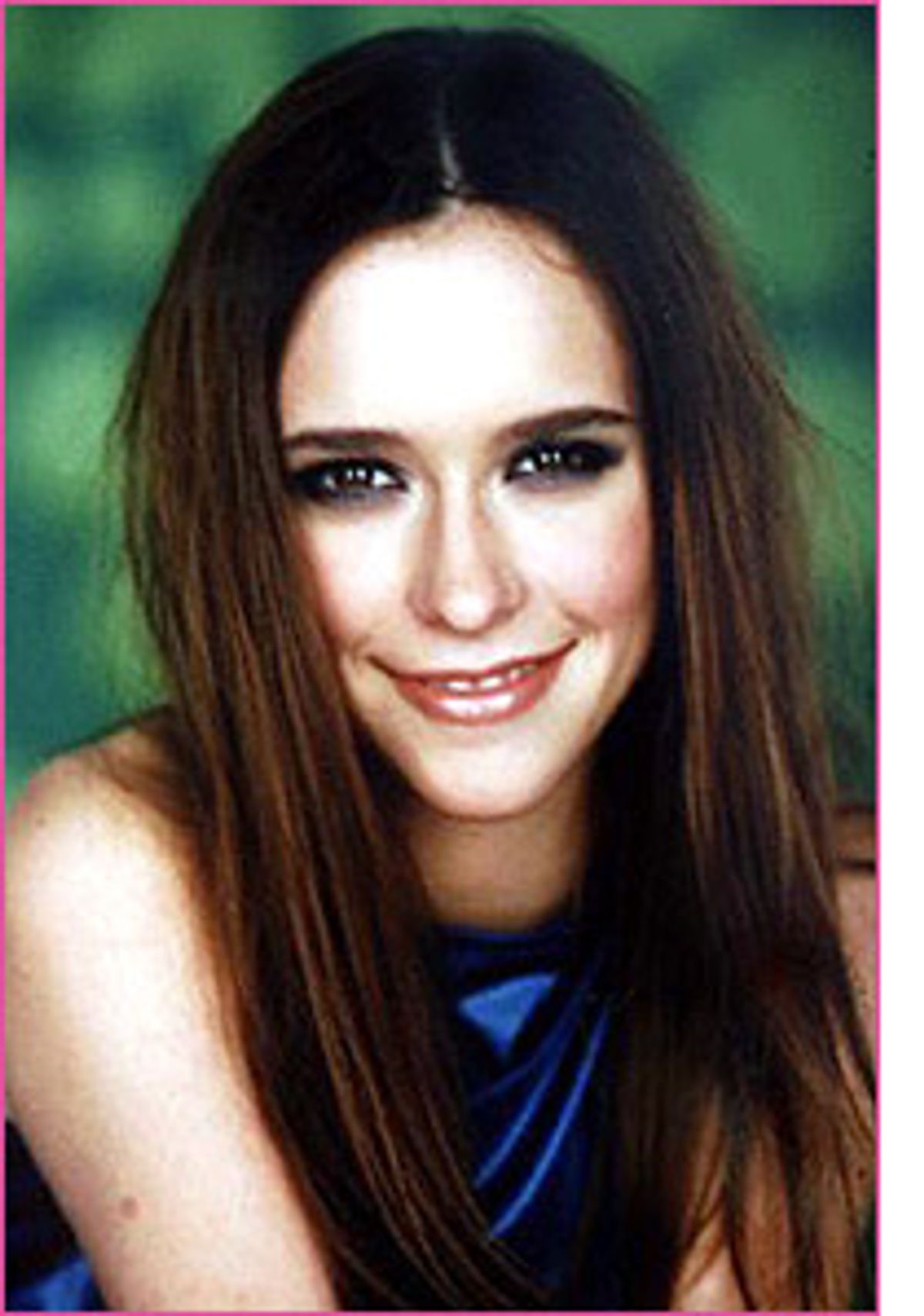

In the normal course of things, directly comparing "Time of Your Life" star Jennifer Love Hewitt to Audrey Hepburn is unfair -- like comparing LeRoy Neiman to Picasso. But with Monday night's "The Audrey Hepburn Story" (ABC, 8 p.m. EST) -- starring and co-produced by Hewitt -- she has made the contrast inescapable. This is not to her advantage.

Hewitt is unconvincing enough as a first time New Yorker complaining about a ridiculously cheap $300 a month rent on Fox's "Time of Your Life." And since Hewitt doesn't possess a trace of Hepburn's charm, grace or magnetism, the interminable biopic resorts to the crudest of script and visual cues. We remember that Hewitt is playing Audrey Hepburn only because she stiffly, emphatically keeps introducing herself that way. As if this were too ambiguous, Hewitt is occasionally shown sliding into various director's chairs, all clearly labeled "Audrey Hepburn." To say the role is a stretch gives Hewitt too much credit. Hewitt's accent is that of a child pretending to be a fairy princess, and her manner is that of a runway model dipped in molasses.

Hepburn's appeal was based in Old World elegance and New World daring. Her style, at the center of films from "Roman Holiday" to "Breakfast at Tiffany's" to "My Fair Lady," was modern but classic, reserved yet alluring. After a short career as a model and dancer, she found an audience in the 1950s and '60s as an alternative to the sexpot sirens who dominated the previous era. She may have been Dutch-English, but she represented something Americans aspire to: class.

Hewitt represents what Americans all too often really are: craven, opportunistic exhibitionists. Most Americans lack her rack, but many of us -- one way or another -- desire it. This may explain Hewitt's astonishing popularity. Aside from her stint on "Party of Five" and the new (but doomed) "Time of Your Life," Hewitt is the face that sold a thousand ad pages by appearing on the cover of the first Teen People, the magazine that's become one of the most successful launches of the decade.

And yet few other stars also arouse such antipathy, even among the generation of teenyboppers whose sole mission is to eradicate all traces of the early '90s (indie rock, riot grrrls, the fetishization of authenticity as a virtue). Hewitt is even hated by the fans of bounce-alikes such as Sarah Michelle Gellar; she's mocked by the same teens she tries to be a role model for. She's said that she won't do nude scenes or use drugs in movies because she doesn't want to do anything on screen that teens shouldn't do themselves. Clearly, that doesn't include being chased by an ax murderer in a wet T-shirt. I hate Jennifer Love Hewitt, too, although it's hard to articulate a good reason why.

"The Audrey Hepburn Story" helps, though. As a biopic, it's just this side of parody. Or just that side. Most of the story is told in clumsily edited flashback (sometimes flashing back from within a flashback) from a "present time" scene that appears to take all of half an hour.

Hepburn's own story is treated just as shabbily. The movie ends midcareer, leaving out her divorce from actor Mel Ferrer and some of her most important and demanding films ("The Children's Hour," "Wait Until Dark"), but also her work for UNICEF as a special ambassador to the United Nations. Maybe the filmmakers saw this as trivia, but even the events within the film's brief take on Hepburn's life are made trivial.

Hepburn's time in a refugee camp, for instance, is glossed over briefly, recklessly, even offensively. And earlier, living in Arnhem, Netherlands, on the eve of the Nazi occupation, Hewitt-as-Hepburn complains to her mother like a teen denied access to the family car: "But you said Germany would never invade Holland!" More important than these formative events apparently -- the entire movie itself hinges upon it -- is whether Hepburn can make Truman Capote smile.

There are many such opportunities to fustigate over the liberties taken with Hepburn's biography, but it is even more entertaining to see what they've done with her clothes. The famously fashionable Heburn is transformed into Christina Aguilera at the prom. Hemlines hike. Necklines plunge. As a performer who could act, sing and dance, Hepburn was what was known as a triple threat. When the busty Hewitt gathers up her most significant assets, however, she displays something more on the order of a double threat: left and right.

It may be a vague awareness of this discrepancy that propels the movie's most revealing subplot: the dancer Hepburn's struggle to learn how to act. Repeatedly, Hewitt-as-Hepburn demurs, "I'm not an actress" and "I can't act." The movie's most painful sequence is a five-minute interlude wherein Hepburn -- magically -- learns how. Would that Hewitt were capable of a similar feat.

There's no need for a 50-minute hour to see the depths of projection Hewitt has brought to the role. Most telling is the depiction of Hepburn's Academy Award win. No doubt Hewitt felt the Oscar acceptance was an important scene. No doubt it is the only time Hewitt will ever lay her hands on one. What may be most appalling about "The Audrey Hepburn Story," though, isn't its inaccuracies or even Hewitt's complete failure to capture Hepburn.

What's striking is the audacity she shows in even trying, and the travesty she makes while doing so. Entertainment is entertainment and for the most part I'm content to let bad television, bad music and bad movies lapse into the category of trivia answers and episodes of "Behind the Music," not quite forgotten, but mostly beside the point.

But "The Audrey Hepburn Story" galls because it's a model for what pop culture has become: the devouring of the past in order to make excrement for the future. Seen this way, Hewitt's inappropriateness as Hepburn almost makes sense; as Hewitt never intended to become Hepburn, she remade Hepburn to be more like her. This explains the biopic's portrayal of Hepburn as man-hungry (falling in love on every set) and petulant, an oddly adolescent pose for someone who in real life was robbed of those years.

Hewitt hasn't just made a bad movie, she's badly rewritten a life.

Two years ago, Hewitt received a "Blockbuster Entertainment Award," one of those sub-Golden Globes trinkets that serve mainly to rationalize the bad taste of the public. But to judge by the relative success Hewitt met with on "Party of Five" (or, as it was known around my house, "Fiesta Del Cinco"), her most significant strength as an actress is her ability to cry on cue.

And Hewitt's eyes carry her through other parts as well. In all of her roles, her expression of emotion is limited to above the nose: She opens her eyes; she opens them wider; she closes them. In especially tense scenes, she gazes sidewise. No matter what the script, it appears as though she's being directed by an optometrist.

Yet there she is. Both Teen People and People dote on her, serving up dozens of pieces in the past two years. Millions of people sat through her star turn in "I Know What You Did Last Summer" twice. Most substantially, she convinced someone she could carry "The Audrey Hepburn Story." Are people that dumb?

With Hewitt's fans, of course, that's an open question. Her fan club offers a "museum quality" "rare lithograph" of Hewitt "arriving at a movie premiere." She's contributed to both volumes of "Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul." The so-called plot of the sequel "I Still Know What You Did Last Summer" turns on the assumption that neither Hewitt's college freshman character nor the audience would know the capital of Brazil.

Meanwhile, a much stronger message is getting through to many other devout Hewitt-watchers. She is, it seems, a lightening rod for pure, untrammeled adolescent hate.

There's a spate of spite sites devoted to desiccating Hewitt on the Web, generally constructed by the same age cohort -- if not the same gender mix -- that adores her. Though the Maxim crowd has paid attention to Hewitt's, er, career, her fixation on being a role model has brought her a fair amount of female fans as well. Non-fans are overwhelmingly teen girls, and their sites (there are seven in the "Anti-Love Ring") are enthusiastic, drenched in the same exaggerated prose and enthusiastic phrase-making that covers fan sites. But while the fans call her "Love," she's known in these parts as "Screwitt."

Hewitt is mocked for a variety of reasons, but a few consistent themes emerge: She is overly cheerful ("Happy-happy all the time"). She is rumored to have dated many demographically appropriate men, from the lead singer of scatter-shot non-sequiturists LFO to the inexplicably inescapable Carson Daly ("Slut"). Most frequently, they complain that she's too, well, attached to her breasts. This is a charge that Hewitt's public statements -- and attire -- do little to diminish. When she called her best-known film "I Know What Your Breasts Did Last Summer" in an interview, it seemed like clever self-awareness. When she told Maxim that she developed "early," and that "my mom raised me to ... appreciate it because it's sort of what makes me me and all that" and that "as a joke" she named them "Thelma and Louise," it just seemed like delusional self-aggrandizement.

Diehard Hewitt-haters will eagerly note the bankrupt symbolism of downgrading celebrated female characters to pet names for her knockers. Considering how the ascendancy of Bridget and Britney to the tops of their respective charts has gone a long way to demolishing whatever remaining base of support feminism might claim among America's young people, a surprising number of sites let Hewitt have it for reinforcing female stereotypes. As one non-fan hyperbolically puts it: "Throughout history women have fought to earn respect and to escape the idea that we're mere objects for men to ogle. JHL is setting us back centuries by stressing that it's not about how much talent or intelligence a woman has, it's the way you look which gives you worth."

But for all their Faludian rhetoric, the attention these sites pay to Hewitt's looks -- indeed, to Hewitt at all -- undermines their proto-feminist arguments. Indeed, addressing Hewitt in particular lets the rest of Hollywood off without even a warning.

That's not the counter-argument presented by Hewitt's fans. (Endearingly, the anti-Hewitt sites often proudly display -- and invite -- the flame mail sent by Hewitt's admirers.) But the method by which the critics counter the fans' most frequent salvo -- "jealousy" -- is revealing: If I am jealous, writes one commentator, "then how come I LOVE all the actresses who have talent and are actually beautiful?"

Certainly, nothing quite betrays adolescent fickleness like the suggestions some sites make for role models that are more appropriate. One site, after critiquing Hewitt, goes on to suggest animatronic toothpick Calista Flockhart as a replacement in the Hepburn role. As far as feminist role models/replacements go, this is a little like exchanging Mary-Kate for Ashley.

These sites take on a distinctly "why her" tone, implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) asking "why not me?" Take this aspiring actress and "former" Hewitt fan's mid-rant concession: "Please don't call Love's clothes slutty and this is why: I have some of the articles of clothes that Jennifer sometimes wears and they are not slutty." In this way, the anti-Hewitt sites are not very different from the fan sites -- those maintained by girls, at least -- whose central impetus is not to question "why her," but to simply be her.

Of course, the indictment of Hewitt could be extended to any 20-something starlet. What's odd is that such an affectless and blank performer as Hewitt could be the one to summon any sort of strong emotion. In the end, however, Hewitt is objectionable not because of an

especially distinctive absence of talent but rather her very ordinariness as a teen role model. In a way, hating Hewitt is easy exactly because she is so undistinguished. She's famous without the veneer of professionalism that's won by appearing in films that are seen by people over 25. She's the kind of celebrity who presents at the Nickelodeon Kid's Choice Award, and who shows up to "Hollywood Bowls" (you know, at a bowling alley) charity events. She still lives with her mom.

For her detractors and her fans, Hewitt is just the other side of normal. What makes someone choose to hate her and not adore her is in the end as mysterious as a crush, and just as normal. In the frenzy of a youth media culture that celebrates fandom like never before (MTV's "FANatic," InStyle magazine, four book-length "biographies" of Freddie Prinze Jr.), we forget that a well-nourished grudge is as important a part of growing up as a first kiss or a best friend. It's probably just as important later. A crush helps you define who you are, a grudge helps you define who you aren't.

And hate, like love, needs an object. Hating Hewitt is the flip side of Tiger Beat, and those who indulge in it are granted a peak through a crack in the mirror glass of celebrity. It's also good practice for down the line, when you discover people and symbols who truly deserve to be taken down, to be driven away by raw disgust -- David Duke, Dr. Laura, whoever invented call waiting. Love makes the world go 'round, but a healthy hatred can keep it from spinning the wrong direction. As one anti-Hewitt essay put it: "Hate is not a bad thing. It is a bad feeling, but is more of a great power."

Shares