When Ali Zaidi visited the University of Rochester hospital in 1994 complaining of respiratory problems, he opened a Pandora's box of miscommunication and half-truths from a community of caregivers who seemed more intent on recruiting human guinea pigs and tallying research grants than on following their Hippocratic oaths. A UR graduate student at the time, Zaidi says he was asked to sign a consent form for a clinical trial he hadn't even been told about by an investigator who called the federal regulations "onerous" and "red tape."

The protocol involved Heliobacter pylori, a bacterium common in gastric ulcer disease, but it was the word "radioactive" that caught his eye just as he was poised to sign. When he inquired about the nature of the study, he was assured that it was perfectly safe. Zaidi refused to sign. After consulting his doctor, he declined to participate in the trial. When he complained about what he called UR's irresponsible recruitment methods, first to the principal investigator, then to the university health services, he says he was disregarded.

It wasn't until 1997 that Zaidi received a terse apology in the mail from William Chey, the principal investigator, that read: "I am sorry to notice that the carbon-14. Urea Breath test was not adequately explained to you to meet your satisfaction. I apologize for the incident." Zaidi, concerned that the study was being conducted with other unwitting participants, had already brought the case to the attention of the Office for Protection From Research Risks at the National Institutes of Health. The Institutional Review Board

called a meeting with Zaidi and the principal investigators, none of whom

showed up. "There are multiple violations" at the University of Rochester, says Zaidi. "They're not informing people about the risks and it's deceptive. It's immoral. They tried to keep me quiet about it." Zaidi is currently embroiled in a bitter lawsuit against the university.

Though the Heliobacter pylori study was eventually terminated and the researchers placed on probation, such recruitment of subjects for research protocols is common on university campuses across the nation. Subjects earn anywhere from a few to thousands of dollars for participating in these clinical trials. Ads recruiting students for research protocols dot the hallways of universities. They appear in student publications and local newspapers. You can even sign up on the Web at CenterWatch for more than 41,000 research protocols around the country, a mere fraction of the trials under way at any given time. Though researchers typically deny any connection between high student populations and clinical trials, those areas dense with students, such as Boston, the Research Triangle area of North Carolina and Austin, Texas, typically have the most protocols at any given time.

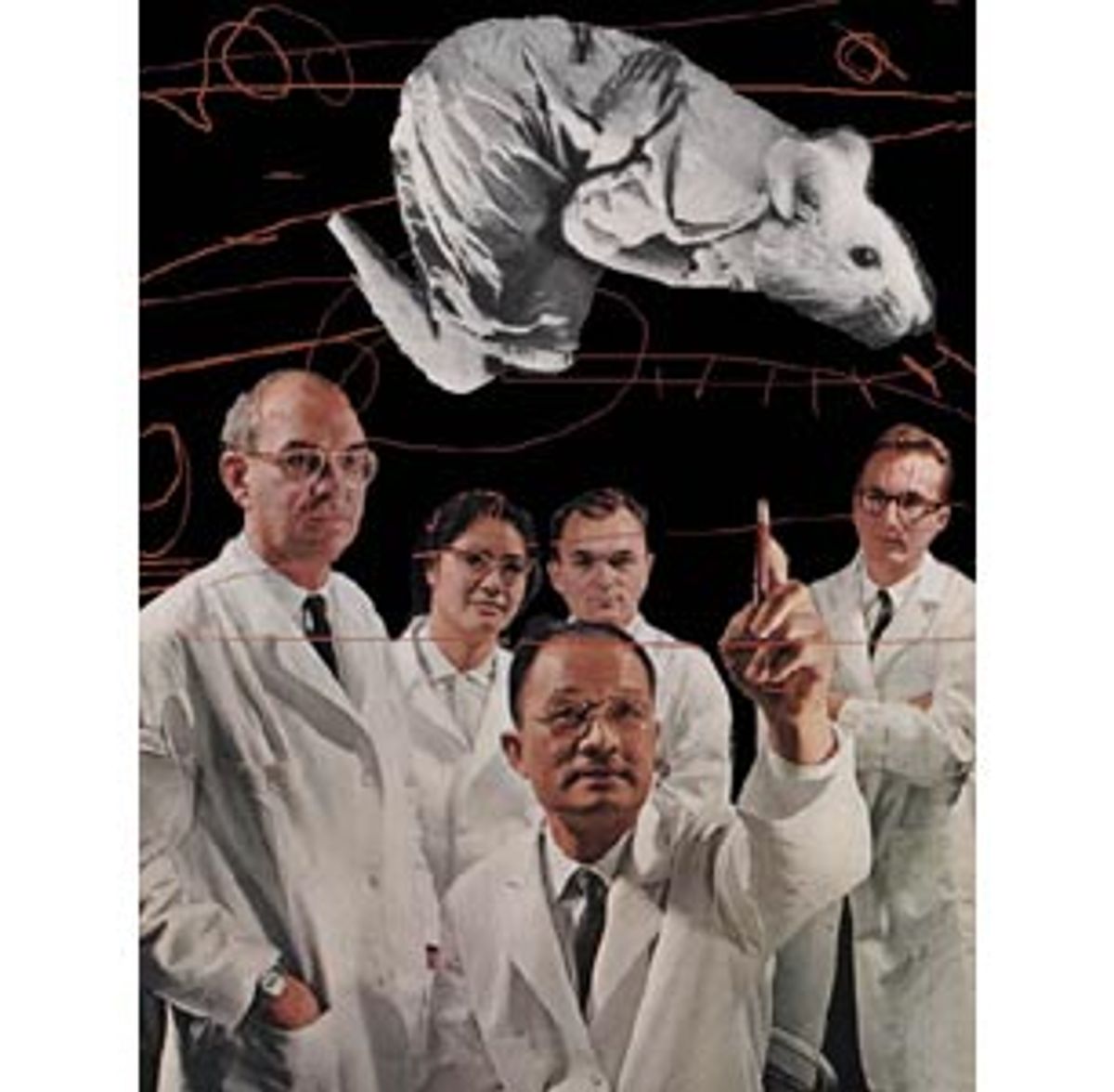

Students as lab rats are nothing new. In the past it was a common requirement for psych majors to participate in their professors' psychology protocols. Students are typically broke, healthy and naive enough not to ask too many questions. But clinical trials have multiplied, and to many investigators, students represent a convenient population from which to draw subjects. "In 1995 we said there were trials across the country that were problematic -- not only with shortcomings but with serious deficiencies," says Ruth Faden, director of the Johns Hopkins Biomedical Institute and chairwoman of President Clinton's 1995 Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments. "In my darker moments I wonder why we don't have more problems."

Problems like Nicole Wan, a University of Rochester sophomore who died in 1996, two days after a routine bronchoscopy (in which cell samples are brushed from lung tissue) taken during a research protocol. Or Jesse Gelsinger, a University of Pennsylvania student who died in September after a gene therapy test.

Eight institutions have had their research protocols involving human subjects halted in recent months after OPRR investigations, the most recent of which were the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Alabama at Birmingham and Virginia Commonwealth University, all of whose trials were suspended in January. Since 1995, 10 percent of the nation's 125 medical schools have been the targets of OPRR investigations, and the office has a staggering 159 investigations under way. This spate of investigations, says OPRR director Gary Ellis, is the result of the OPRR's becoming more efficient in identifying problems in the wake of U.S. Inspector General June Gibbs Brown's criticism of the office in a 1998 report on human subjects protection.

Such research protocols have long been a method for scientific advancement -- and have long been marked by abuse. A recent Chronicle of Higher Education article reported that only 17 percent of the illnesses or deaths suffered during gene therapy trials were promptly reported to the National Institutes of Health. Faden's advisory committee identified 4,000 federally funded radiation experiments between 1944 and 1974 involving human subjects, including the well-publicized 18 people at the University of Rochester who were unknowingly injected with plutonium in the 1940s. From 1932 to 1972, the U.S. Public Health Service conducted the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which poor black men in Macon County, Ala., were given free treatment for "bad blood." The "treatment" actually entailed the withholding of treatment for syphilis, which was then epidemic in the area, to see how the disease would progress unchecked. The uncovering of the study eventually led to a formal apology in 1997 by President Clinton.

The real problem, according to many researchers, lies in the definition of informed consent. After all, the word is "informed," not "begrudging." Most researchers conduct a risk-benefit analysis for any clinical research trial even before the trial is proposed to the granting agency. Once the trial is approved though, briefly going over the risks and benefits with a subject who sees mainly the possibility of earning a little money hardly seems an adequate method of securing informed consent. "As the risks escalate," says Faden, "then it becomes important to consider the maturity and vulnerability of the subject." Zaidi, the Rochester student, says benefits and risks were never discussed with him.

The University of Rochester is now conducting a study called UPREST, which involves healthy and asthmatic patients inhaling 10 micrograms of carbon and iron oxide per cubic meter of air -- a very small amount. "There are no known undesirable effects," the consent form reads, listing some possible side effects such as coughing, throat irritation, bruising where blood is drawn or soreness around the mouth from gripping the mouthpiece.

But the Environmental Protection Agency's National Center for Environmental Research and Quality Assurance tells a slightly different tale. While UR's informed consent form says no symptoms are expected from the small amount of particles inhaled, the expected results from the study listed on the NCERQA Web page state: "UFP [ultrafine particle] exposure will result in mild airway inflammation, preceded by sequential expression and shedding of endothelial [the top layer of blood vessels] and leukocyte [white blood cells] adhesion molecules, and accompanied by a transient acute phase response [immediate] and increased blood coagulability." If no subjects show side effects, the carbon levels will increase to 25 micrograms per cubic meter -- still within the range of what the EPA considers safe to inhale. Subjects are paid $400 for participating.

According to Dr. Mark Frampton, principal investigator of the study, this research is one small piece in the larger puzzle of how to determine safe air standards. While most of us likely breathe in this amount of carbon naturally every day, at issue is how the consent form reads. It claims there are no known undesirable effects, but few research subjects will ask about the possibility of unknown effects. The information present on the form is a watered-down version of what appears on the NCERQA Web page.

And further, the form fails to outline the fact that while carbon is in the air we breathe daily, the real danger lies in the particle size. Our bodies have the means to combat larger particles; it is the ultrafine particles that present the most hazard, since they attach to the alveoli in our lungs and can cause respiratory problems or tissue damage. Frampton, who was one of the researchers in the study that involved Nicole Wan in 1996, says the researchers don't "plan on going to levels dramatically in excess of what a person might be exposed to in ambient air or in the industrial environment," but he concedes that "there've been some studies that suggest ultrafine particles may have [undesirable] health effects." Frampton says these results have not been proved, though one professor I spoke with (who wished to remain anonymous) said ultrafine particles are widely recognized to be the most hazardous.

Frampton's UPREST may well produce important results about pollution levels in the same way that lopping off a limb could lead to advances in prosthetics, but the study has raised a red flag. It is one of many Rochester protocols under investigation by the Office for Protection From Research Risks. (This is the second investigation at Rochester; the first followed Wan's death. All research involving human subjects was suspended and the university's review methods were revamped.)

"When people review research, really what we're doing is making a guess about the prospect that something beneficial will come from the research," says Faden. "But we're also making a guess that something harmful won't happen. The language is a problem with benefits and risks," she says, "as in: 'Benefits' are sure things and harms are 'risks.' It ought to be the prospect of benefit, the risk of harm, if we really wanted to keep the two clear in our thinking."

The regulatory standard, according to the OPRR, is for the consent form to describe completely any foreseeable risks or discomfort to the subject. "Shortcomings in the informed consent process [arise] in a distressing number of instances," OPRR director Ellis says. OPRR investigators "often find understatements of risks and overstatements of potential benefits ... That's wrong. Researchers are best to err in the conservative direction."

Rochester Provost Charles Phelps admits that the university's "paper trail was thinner than it should have been" prior to Wan's death and that there is now a more vigorous review process in place, though he denies that the university is responsible for the Wan tragedy. "We are convinced now that events that led to her death, as tragic as it was, were not events that would lead us to want to remove Dr. Frampton or other people involved from carrying out clinical work or clinical studies." Phelps declined to comment on Zaidi's pending lawsuit.

Jonathan Moreno, director of the Center for Biomedical Ethics at the University of Virginia, cites a philosophical principle dating back to the 1970s that "goes beyond consent to justice. And justice means you spread out the benefits as well as the burdens of research. Unfortunately, we don't spread out the benefits at all because of our health care system, but we try to be just in spreading out the burdens."

Moreno wrote about the burden of vulnerable populations in clinical trials in a chapter of "Beyond Consent," an anthology discussing the notion of justice in research trials. He defined vulnerable populations as those not in equal balance with researchers because of social context: students, for example, or people with economic hardships. Eighteen may be the age of consent, but when the protocol stems from a researcher at a student's own university, how much does the uneven balance of power play into the student's decision? How many of us, students or otherwise, question our own doctors?

Frampton says he and his colleagues try to maintain a demographic balance when signing up participants, though he concedes that they mainly place their ads on bulletin boards. And in a place like Rochester, where the poverty rate in the city proper is nearly double the national average -- 22.5 percent vs. 13 percent -- economic necessity must factor into a participant's decision to sign on the dotted line. "Poor people are very vulnerable because their life circumstances are such that they feel compelled to do something for money that someone who is better positioned in life wouldn't even consider," says Faden.

The University of Rochester was one of the first to undergo an extensive OPRR investigation, and Frampton says that today's Institutional Review Board is more efficient and better funded, with much clearer guidelines. But it is alarming, notes Moreno, that even under the stricter guidelines adopted in 1991, schools such as Rochester "have no way of knowing how many experiments you volunteered for in the past several years, [but] they know exactly how many laboratory animals they've used."

One major shift in the way research is conducted these days is that many investigators now function inside a new entrepreneurial kind of university. Numerous articles cite the 21st century professor who has financial stakes in a market that hires inventors in droves to discover new drugs and treatment methods. In a climate where more grants are available and more trials are conducted, there is a greater risk that certain standards will be overlooked. "The number of subjects is larger, there's more money and you have multiple-site studies that are hard to coordinate," Moreno says. "The licensing and commercial factors are huge."

When Jonathan Swift published "A Modest Proposal" in 18th century Ireland, he offered a sure solution to the country's economic ills: The poor could sell their year-old children as food to the rich. God-fearing citizens were outraged. Eat the young of the less fortunate? Never in this civilized society! And even to those clued in to Swift's irony, his point was largely missed -- namely, that any proposition couched in calm tones and reassuring language could be made to sound reasonable. In modern America, the missing word, according to the OPRR's Ellis, is experiment. "It's almost never used," he says. "You'll hear people talk about gene therapy, but it's not therapy, it's experimentation. You virtually never see that word in informed consent documents."

"The frank reality is that we're not going to make the progress we want to make unless we do some of the more risky human subjects research," says Faden. "Given that we want the progress, we have a duty to make sure the subjects are protected as well as we can. And we're not doing that."

Shares