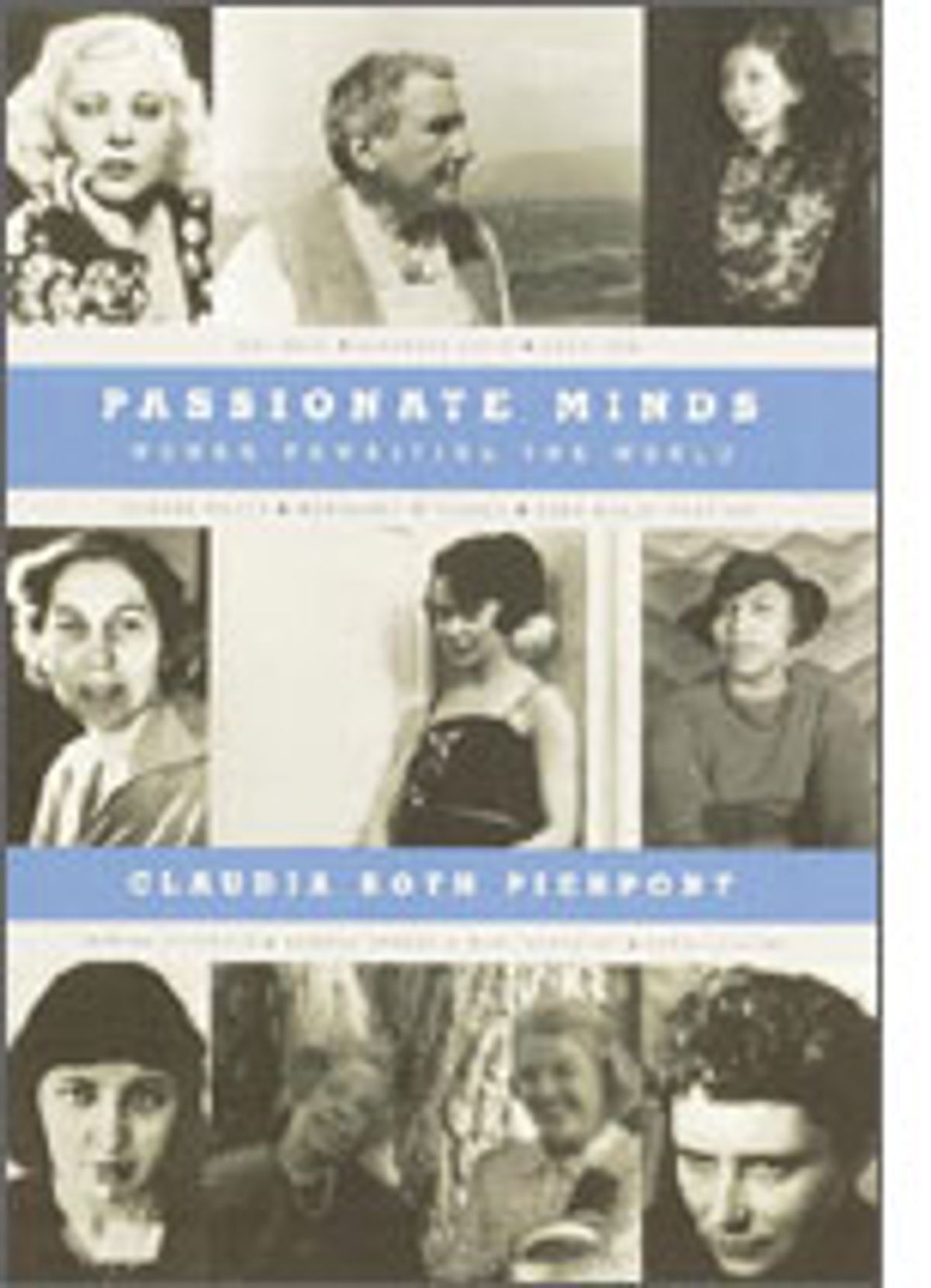

In "Passionate Minds," her collection of critical essays -- all of them originally published in the New Yorker -- Claudia Roth Pierpont considers a dozen female writers of widely disparate sensibilities. What were her criteria for including Hannah Arendt in the same volume as Margaret Mitchell, not to mention Mae West and Ayn Rand? Simple: They are "literary women of influence (very different from women of literary influence) whose domain is somewhat off the usual critical path." These writers wielded power, often out of proportion to their artistry. They started cults (Rand), engendered myths (Mitchell, of an Old South that never existed) and defined the self-perceptions of an entire generation of women (Doris Lessing, with "The Golden Notebook").

None of the subjects of "Passionate Minds" has escaped the attention of prior critics. The 1970s saw the rediscovery of several who had dropped from sight, including Olive Schreiner, Anaos Nin and, most notably, Zora Neale Hurston. In a sense, then, Pierpont's contention that these writers are off the usual path more accurately describes her own approach to them. She traces the connections between their lives and work with ease, treading lightly between the twin snares of polemic and psychoanalysis. Each of these portraits constitutes a short but satisfying critical biography; each contains at least one line so right that you can't resist reading it aloud. (For example, Pierpont notes that Lessing's forays into science fiction beginning in the late 1970s "inspired more critical shock than should have been felt by anyone who'd read 'The Four-Gated City' or, for that matter, by anyone who paused to think what a furiously willed sense of fantasy it required to remain a Stalinst through the mid-1950s.")

The first piece, on South African writer Schreiner, establishes many of Pierpont's major themes, including the problem of reconciling love (and sex) with literary achievement and the enduring influence of mothers. Schreiner's own mother was implacable; she raised her children in a hut yet "charged herself with the perfect preservation of London drawing-room gentilities." Her strength both repelled her daughter and equipped her to write "The Story of an African Farm," a novel that found a huge audience among Victorians who had lost their religion yet sought some sort of spiritual comfort.

Pierpont's other subjects were similarly scarred or inspired by the maternal example. West learned the all-important lesson from her mother that "one man was about the same as another." Throughout her life she carried a photo of her adored parent, carefully retouched with West's own cosmetics. Mitchell's mother, who was simultaneously a suffragist and an apologist for the lost Southern cause, tried to chivy her child into acquiring an education. Mitchell resisted vehemently but went on to create a heroine who was strong-willed and independent, if as hollow (Pierpont notes) as Mitchell herself.

The mother-daughter struggle figures most fiercely in the life and writing of Lessing, whose rebellion against her unaffectionate mother began with teenage sexual activity and may have included her abandonment of the two small children from her first marriage. "To a reader," Pierpont writes, "comes the awful but unavoidable thought that Lessing may finally have duplicated her mother's perfect two-child family precisely in order to throw it away."

Which brings us to another quality of these women's lives: that "children are nearly impossible" in them. Though many of them married, unhappily or often or both, only three produced offspring. Mary McCarthy's relations with her son, Reuel, are not recorded here. Lessing did raise a third child but dispatched him to boarding school at the age of 12. As for Marina Tsvetaeva, the Russian poet of all-encompassing romantic love, she responded to the privation that followed the October Revolution by putting her young daughters in an orphanage. Although she soon rescued her older (and favorite) child, the younger one, who was only 2, starved to death. Ironically, it is Gertrude Stein who emerges as a fount of maternal love; Pierpont depicts her as realizing, at the end of her life, that she had been "giving and feeding and advising and encouraging and (is there another word for it?) mothering [the] men whom she loved and admired."

In truth, most of these women made life nearly as difficult for those around them as they did for themselves, with the exception of Eudora Welty. (Pierpont makes a convincing case that Welty willed her once unruly art into the constricted work of a perfect lady.) The ancient question bubbles up: Is bad behavior the prerequisite of creativity? And so, almost immediately, does the feminist answer: If these were men, we wouldn't bother to ask.

That Pierpont explores the issue and delivers a nuanced response is one of the many pleasures of this book. She is surprisingly sympathetic to Rand, self-proclaimed prophet of selfishness, pointing out that her "novels are riddled with syntactical loopholes that permit ... just the compassionate behavior she claims to disavow." Yet Pierpont never hesitates to issue a verdict when one is needed. "The real and bottomless subject of Nin's diary is not sex, or the flowering of womanhood, but deceit," she asserts, echoing McCarthy's declaration that every word Lillian Hellman wrote was a lie, "including 'and' and 'the.'"

Although Pierpont has expanded and revised many of these essays since their first publication, some evidence remains that they began life as book reviews. Yet their wit, conclusions and unwavering intelligence make this second appearance (unlike some gatherings of magazine assignments) seem absolutely necessary.

Shares