Every day, Ephraim Mett works a mouseclick away from damnation. Mett, a programmer at Jerusalem's MALAM Systems Ltd., spends his day writing code and developing Web sites for clients like the Israeli post office. But, as a member of Israel's ultra-Orthodox Jewish community, he is forbidden to browse the Web or shop online; this would be frowned on by his rabbis, who have branded the Net a "danger thousands of times more serious" than television, one that could bring "destruction and ruin." In January, prominent ultra-Orthodox rabbis banned their followers from using the Net for purposes other than work.

When Mett comes home to his young family, he steps back into a traditional world that has more to do with "Yentl" than Yahoo. Mett says he wouldn't put a connection in his home or use his Web browser at work for shopping, even if it was to buy something as innocuous as a sofa. "Obviously, it would be very useful to use the Internet for such a thing," he says. "The problem is that the Internet has a lot of power to draw a person in, which is why I understand the ban fully and respect it."

Like other ultra-Orthodox programmers, Mett (who did six years of advanced religious study before joining MALAM) straddles a strange divide: With one foot firmly planted in the ancient and insular world of Talmud study, he is stepping into the fast-paced, globally oriented world of programming. Curiously, his religious background might be his greatest asset as a programmer. "The analytical approach used in Talmud is very useful for programming," he says. "You have to work out plausible explanations, which are quite a lot like programming algorithms."

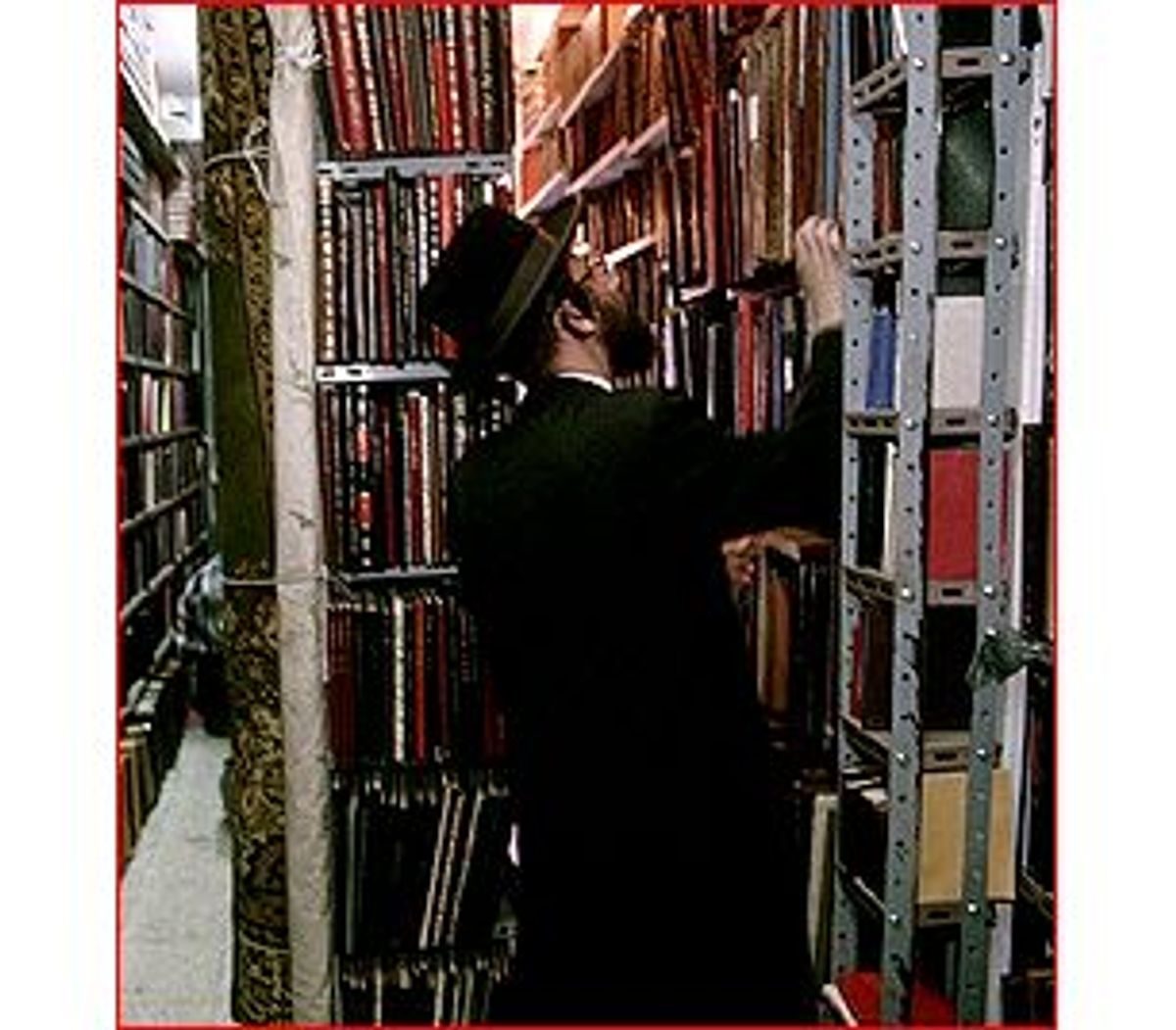

Until recently, it would have been almost impossible for Mett and his ultra-Orthodox, or haredi, peers to work in a high-tech company. Prejudices on both sides and a lack of technical education barred their entry to "Silicon Wadi" -- the collective name for the industrial parks and incubators springing up all over Israel's desert landscape. Now, with increased educational options, the ultra-Orthodox are entering Israel's high-tech world in significant numbers -- and finding that their skills are in high demand.

"I'd be happy to employ more haredi programmers," says David Schindler, a vice president at MALAM. "They're older and more mature, and they have a tremendous drive to succeed." Besides, adds Schindler, who was a religious scholar in his youth, Talmud study is excellent preparation for programming. "It gives you an intuitive mind; you know how to break problems down into the smallest particles."

In fact, the Talmud -- first compiled in the year 200 B.C. -- was ahead of its time both aesthetically and intellectually. Looking at it might explain why "the people of the book" are natural converts to hypertext: In many ways, the Talmud looks like a blueprint for Web design.

Consider the Babylonian Talmud, the work of many generations of rabbis. When this transcription of oral law was started, Roman occupiers were attempting to wipe out all traces of Judaism: life was a little stressful, and the original text, the Mishnah, came out disjointed and nonlinear (imagine Moses communing with James Joyce). Succeeding generations of rabbis saw the Mishnah as a good start, but decided to add their own interpretations to it. On a typical Talmud page, these writings ("Gemara") are placed in discrete blocks in a tree-ring formation around the Mishnah -- with cross-references, links to other sections and arcane symbols and abbreviations. The effect is of a virtual discussion forum between rabbis from different centuries. "It's actually the world's first hypertext," says former Israeli Minister of Energy Yossi Vardi.

Talmud pages are "busy, non-linear, filled with different typefaces, graphical symbols, parallel and intersecting frames, and even multiple languages," writes Edmond H. Weiss, an associate professor at Fordham University's Graduate School of Business Administration, in "From Talmud Folios to Web Sites: Hot Pages, Cool Pages and the Information Plenum." Each generation of Talmud scholars is encouraged to produce its own interpretations, the very best of which might be incorporated into future editions of the text. To read the Talmud, Weiss posits, "you join the conversation. Just like the Net."

Of course, with so many voices, there are bound to be disagreements. The Talmud contains notorious arguments between rabbis. In studying the text, part of the scholar's task is to decode and reconcile these differences, discovering an underlying system by which the different points of view can coexist.

Imagine, for example, that an updated Talmud was to deal with malfunctioning Web browsers (this is not so far-fetched, since it deals with such minutiae as the direction a person should face while defecating). Replace rabbinical authorities with programmers and a section might read as follows:

Adam believes that his Web browser is crashing because he hasn't upgraded to the newest release. Bill says that Adam is using too recent a version of the software. Both are experienced programmers. How can this disagreement be? Carla, another programmer, says that if the problem is file-system corruption, Adam's theory would apply, but if there are problems with certain embedded Web objects, Bill would be right. Danya had problems with embedded objects, and found that the solution was to disable certain audio plug-ins. So it seems likely that Bill is referring to problems with portable document formats, whereas Danya's issues concerned streaming audio. Did Erin manage to fix her system by removing plug-ins? Doubtless she had encountered the streaming audio bug, too.

"I must give credit to the years of studying Talmud, which opens their minds," says Rabbi Yehezkel Fogel. In 1996, Fogel founded the Haredi Center for Technological Studies, the community's first technical college. Since the ultra-Orthodox can't attend secular schools (they're prohibited from studying in co-ed classrooms) the center acts as a necessary bridge between the worlds of Talmud and high tech. Having opened in 1996 with 35 students, it now boasts an enrollment of 1,200 in five locations across Israel.

In setting up the school, one of the major issues Fogel hoped to address was poverty in the community. Traditionally, haredi men study in a yeshiva full time into their 30s and beyond, while their wives support the family, often by working menial jobs. Add to this the stress of dealing with a large family (often up to nine children) and it's easy to see why 51 percent of ultra-Orthodox Jews in Israel live below the poverty line, as opposed to 15 percent of new immigrants to Israel and 24 percent of Arab Israelis.

Fogel, who is a staunch advocate for technological training, was one of the first people in the haredi community to recognize its potential to bring economic and social change. Even so, "it wasn't easy to come and introduce this idea," he says. "At first, we were very worried about upsetting mores in the community."

Yet prominent haredi rabbis -- of the Hasidic, Ashkenazic and Sephardic sects -- proved surprisingly amenable when asked to give the school their blessing. "They live among their people; they understand the needs of the community," says Fogel, who sighs and adds, "Normally, it's unusual that they'd agree on anything."

Then again, says professor Daniel Hershkowitz, "the idea is not to be disengaged from the world of the Talmud." Hershkowitz, chairman of mathematics at the Technion/Israel Institute of Technology, was instrumental in setting up courses at the Haredi Center for Technological Studies. "At first, they were hesitant about such a connection, because universities are known to be associated with unbelief," he says. Being an ordained rabbi helped Hershkowitz convince haredi authorities to accept a collaboration with the renowned university.

In setting up the school, Fogel and Hershkowitz had to cater to an unusual student body. While 70 percent of ultra-Orthodox men have spent 20 years or more in advanced religious study, they lack basic secular education. To bring them up to speed, students take general courses during their first three months at the center, then move on to specialized computer courses. When they graduate, they get a diploma from the respected Technion, which Fogel says is "very meaningful to employers.

"We tell employers that our graduates are not quite the same as college graduates, but they're well prepared and can prove themselves on the job," he says. If the proof is in the paycheck, Fogel's right: many of the school's graduates report that they've doubled or tripled their salaries within a year of employment.

One student who's banking on that kind of success is Anat Rafaelo, a mother of five from Jerusalem. Rafaelo sports a sheitel, the wig ultra-Orthodox women wear to shield their hair from men other than their husbands. She says she's wanted to program for a long time. "I was working for a company before, and I wanted to program, but they saw I didn't know much so they put me to work in quality assurance."

At MALAM Systems, where Mett works, there are now 30 other ultra-Orthodox employees; they constitute 3 percent of the company's staff. Schindler, the MALAM vice president, says they represent an ideal work force. "They're used to sitting for many hours without taking a break, or getting up to chat and drink coffee," he says. "They're very focused."

Schindler admits that it took a while for the company's secular employees to get used to "the black hatters," as the haredim are often called. Once the first hurdle was over, however, the rapport was "fantastic. We all agreed that the public perception of these people was hogwash."

In a country where religious and secular groups have become increasingly polarized and hostile, the social and political ramifications of this are enormous. On both sides, fear of the "other" is decreased by daily contact at the office. On a lighter note, there's another interesting side effect of the haredi entry into high tech: It might be bringing a newfound modesty into the Israeli workplace.

"It has affected the way people dress," says Schindler. "When they're working with someone dressed in beard and peyot and a long jacket, it's not appropriate for a woman to wear a short miniskirt."

The haredim's modesty code also places limits on the kind of work they can do. "Designing a Web site for a swimwear company wouldn't be a problem," says Shlomo Kalish, CEO of the venture capital firm Jerusalem Global. Kalish, who belongs to the ultra-Orthodox Hasidic sect, reads the Kabbala and the Talmud in his spare time. "Developing Playboy's Web site would be problematic," he says.

Despite such fine distinctions, some haredim have made the bold step of starting their own companies. Shlomo Unger, a teacher at the Haredi Center, was so impressed by its students that he created a start-up with four of them. Wizapp, whose 40-strong work force includes 10 ultra-Orthodox employees, is beta-testing an Internet database software package that Unger expects to launch this month or next.

Wizapp also got a huge boost when Yossi Vardi joined its ranks as a seed investor and consultant. Vardi, who divides his time between half a dozen Internet companies, is seen by many Israelis as a kind of technological Midas. (The touch extends to his son, Arik, who created the globally successful messaging software ICQ, which was acquired by America Online in 1998.) Vardi says he joined Wizapp because he felt that the company's software was marketable, but also because its owners were "very productive, very motivated and very sharp-minded" from years of studying the Talmud.

A secular Jew, Vardi says he sees Fogel's center as a model by which the less advantaged can be incorporated into the information economy. "Until the Internet came along, the Israeli high-tech scene was enjoyed solely by people who had a computer background, and there was a high correlation with socio-economic background. Now, people with creative talents in art and humanistic study can also become important players in the field. I was elated to have an opportunity to provide haredi youth with a path that would turn them into productive members of the economic life of the country."

And perhaps, into political moderates. Known for its extreme positions on issues like the peace process and the nation-souring "Who is a Jew?" debate, the ultra-Orthodox community is often characterized by its fanatical edge. The unspoken hope in Vardi's statement, echoed by many Israelis, is that technology will act as a mainstreaming force in the community.

And that, clearly, is what has haredi rabbis scared. In the past, insularity and poverty have been integral to the haredim's spiritual and political paths. Whether they can successfully negotiate a spiritual path through cyberspace remains to be seen -- and the rabbis, in issuing a ban against the Internet, are taking no chances.

Ultimately, though, ultra-Orthodox rabbis may have more to fear than the lure of X-rated Web sites and material goods. On a root level, working in high tech may be changing the way their followers relate to the world. "Haredim are not used to improvising," says Unger. "They're used to listening to rabbis and doing exactly what they're told." In the past six months of setting up his start-up, he says, "one of the things I've been doing is teaching them to use their imaginations, be original. They're very humble and this is strange for them, but I've seen very much success."

Unger cites the case of one ultra-Orthodox worker at Wizapp, a woman who is supporting eight children and a husband who studies full time in a yeshiva. "She's a wonderful programmer. But when she started, she was very shy -- she looked at the ground and didn't speak to anyone. After a few months, she started to speak a little differently. She's clearer and more direct. She's become more open."

The woman, says Unger, is "bringing money back to the family, and the whole family is enjoying a new way of life. She can afford better clothes. Her kids see the new options that the Internet and the computer industry is bringing them, and I don't think that they will go back to closed communities. No," he pauses, then adds thoughtfully, "now that this path has opened to them, I really don't see a way back."

Shares