As an author whose first book, a collection of stories and essays titled "Men My Mother Dated and Other Mostly True Tales," is just weeks away from appearing in bookstores, I've found the path to publication fraught with tiny battles that yield both frustrating defeats ("What? No appearance on 'Oprah'?") and unexpected victories (a very funny foreword composed by NBC sportscaster Bob Costas, to whom I used to serve an occasional burger back in my food service days).

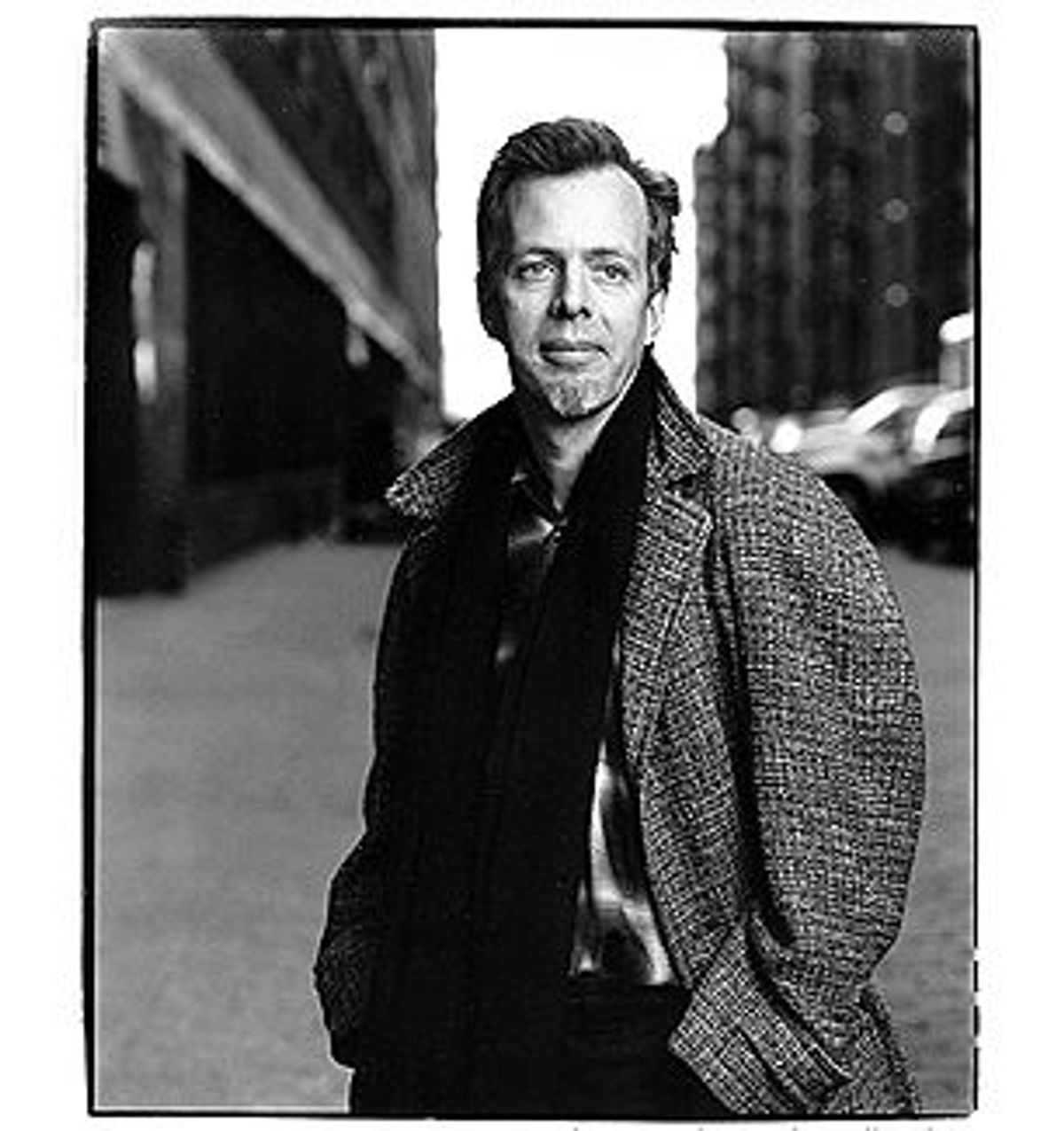

But my most serendipitous coup came the day that Annie Leibovitz agreed to take my author photo for

the book jacket. Leibovitz's witty artistry and my pedestrian puss -- there hasn't been a pairing this unlikely since Michelle Pfeiffer dated Fisher Stevens. I feel like the schmo who stops in for a pack of gum and is awarded a shopping spree when it's announced that he is A&P's millionth customer.

I met Leibovitz a year ago when I was part of a small group of people invited to her studio to get a sneak peek at her then-in-progress book, "Women." It appeared she was in the process of making final shot selections and deciding how they might best be ordered. "Don't worry about stepping on them," she assured us more than once as we wended our way through the prints that lined the floor, "they're only photocopies." But it was hard to allow oneself to tread on those wonderful images, many of which were so unlike the whimsical celebrity photos so often associated with her. Instead we tiptoed along the 6-inch spaces between the rows where the concrete floor peeked through.

After a bit, I wandered over to chat with Leibovitz. I pointed out those images that I especially liked and asked a few questions about the process of working with such a large and disparate group of subjects. The conversation was a brief one, as was our stay at the studio, but on our way out, I told Leibovitz that I hoped to interview her when the book came out and she seemed agreeable. I had my doubts, though, as to whether she would remember, several months down the road, that she'd made such a promise.

But she did.

Now it's October, "Women" will soon appear in bookstores, and after I contact Leibovitz's publicist at Random House, a date is set for the interview. I'm told that she's agreed to do only a handful of interviews in support of the book, so I'm surprised to have made the cut.

"I've been looking forward to this," she says as she welcomes me to her new West Chelsea studio on the appointed day. "You were the only one to speak to me that day at the old studio. All the others seemed intimidated or something, but you had such kind things to say and asked such interesting questions."

I'm stunned. Not for a moment would I have believed that she would have the slightest inkling that she and I have ever met before.

As we sit down to do the interview, I tell her that we're fellow Random House authors, that my first book is to be published by Villard, one of Random's imprints, in the spring. She asks a couple of questions about my book and we settle down to begin the interview.

It flows easily, more conversation than Q&A. We talk about the early days of her career, about our shared fascination with Mississippi, about how one can sometimes feel trapped by success.

As I pack up my gear at interview's end, I say, jokingly (OK, half-jokingly), "So, Annie, I have to ask: Do you offer a discount to Random House authors? Because, you know, I need an author photo for my book."

Am I fantasizing that she might somehow agree to shoot me? Yes, of course, but what I really expect is that she'll laugh off my silly little suggestion, thank me for my time, point me toward the door and get on with her day. Instead she says, "Oh, you need an author photo? Great, let's do it!"

I am nearly speechless.

It takes several weeks to finally pin down a date for the shoot. Two or three dates are agreed upon, but each time Leibovitz's assistant calls a day or two in advance to reschedule -- which I find worrisome, as I harbor a sneaking suspicion that the universe couldn't really be so out of whack that I will actually be allowed to sit for Annie Leibovitz. I'm fearful that there must surely be an out-of-control bus somewhere with my name on it intended to set things right before I make it safely to Leibovitz's studio.

Finally, an arranged day and time arrives without postponement. I gather a few shirts, two or three pairs of pants, a couple of sweaters and two sport coats and make my way to Leibovitz's studio.

Here's what I expect will happen: Some underling will take a quick look at my clothes and, with a grimace, say "That shirt and those pants," and plant me on a stool in front of an arty gray screen. Leibovitz will appear, a few pleasantries will be exchanged, she'll shoot 10 or 15 quick shots and I'll be politely shown the door.

I'll be there 30 minutes, tops.

But that's not what happens. Instead I enter the studio's front office, where several assistants, most of whom I met the day we did the interview, greet me warmly. Leibovitz is not cooling her heels in some back room; she's right here and seems happy to see me.

"You must be a nervous wreck," she exclaims. "It's so nerve-racking to get all ready for something like this, and then have us pull the rug out from under you over and over." In fact, I didn't find the postponements all that unsettling. But I find it utterly charming that Leibovitz is concerned that I might have. She comes over, embraces me in a big, warm bear hug, and gives me a good shake, saying, "That'll loosen you up." And it does.

We enter the studio. There are several assistants puttering about, gathering equipment and making preparations. Leibovitz and Kim, a stylist for the shoot, watch as I display the clothes I've brought; a few ensembles are agreed upon, and Leibovitz announces that we're going to begin with street shooting, and then return to the studio.

The shooting process is great fun. Kim pops over every three or four shots to adjust the sleeve of my coat or the collar of my shirt. She musses and unmusses my hair. She makes sure my scarf catches the breeze just so.

We're set up on a side street a couple of blocks from the studio -- Leibovitz, Kim, a phalanx of assistants manning huge lights, reflectors and other assorted equipment and me -- so it is only natural that pedestrians who pass us on the sidewalk and people who watch from their cars as they motor by might assume that I, positioned at the eye of this creative storm, am ... someone. In fact, at one point, I happen to glance in the direction of two young women who have, for quite some time, been watching the proceedings from a few yards away; they smile at me flirtatiously and offer fluttering waves.

This does not happen to me. Young women do not smile at me on the street; they do not wave. These gals clearly think I am ... someone.

In truth, I am not someone, not in the sense that these people suppose me to be. Ricky Martin is someone. Calista Flockhart is someone. Leibovitz herself is someone. But because her camera is turned on me, in the eyes of those passing by, I become ... someone.

Of course all celebrity is fleeting, and faux fame is the most transitory of all. Mine ends as soon as we return to Leibovitz's studio for some interior shots. Most of these find me seated, leaning raffishly against what looks to be the same picnic table where Leibovitz and I conducted the interview several months prior.

After an hour of shooting in the studio, it appears we're about ready to wrap it up. After all, I've been there a good two hours already, far longer than I'd ever dreamed I would be, and we've surely managed any number of shots that will suit my purposes. But Leibovitz, looking over the Polaroids (she uses a camera that shoots out an instant photo as it exposes a negative), isn't satisfied.

"I like your beard in person," she says of my tiny goatee, "but I'm not sure it's working in all these shots. Why don't you shave it and we'll shoot some more?"

Fine by me, of course. I'm not going to decline the opportunity to have Leibovitz shoot another round of pictures of my mug. She sends someone out for a razor and shaving cream and, upon their return, I head for the bathroom and off comes the goatee. We do another 30 or 45 minutes of shooting before I make my way back out into the chill Manhattan afternoon, walking approximately 6 inches off the ground.

Still, it is when the first prints from that session arrive by messenger for my consideration that my worldview is most decisively altered. Here are lush, elegant, beautifully lit photos of the type that one might see in any given issue of Vanity Fair, of Vogue, of Harper's Bazaar. But it is not Gwyneth Paltrow depicted in these photos, not Brad Pitt, not Rupert Everett.

It is me.

I have long had a complicated, even conflicted self-image. When I stand before a mirror, I sort of like what I see. I don't kid myself that I'm any kind of Adonis, but that man in the mirror has a pleasant, open and friendly countenance that strikes me as not so hard to take.

The problem has always been finding others -- particularly single, female others -- who agree with me.

But in these alchemistic photos, Leibovitz has performed some kind of wonderful voodoo. She's found the elusive me that I see in the mirror and captured it for all to see.

These pictures are how I will look in heaven.

Imagine you were someone who enjoyed playing golf, but who showed no aptitude whatsoever for the game. A mere duffer, you felt lucky when you managed to finish 18 holes with a score in the high double digits.

But one day, miraculously, you shoot an even par game. You don't set the course record, you don't shoot a hole-in-one. But you complete a round with a score much lower than you'd ever hoped you might achieve.

I suspect your whole outlook toward the game of golf would change. Sure, you'd return to your hooking-and-slicing ways soon enough, but never again would you despair that a finer game was out of your reach. You'd live your life with the knowledge that one day, if conditions were just right, if the stars were aligned just so, you could again be a scratch golfer, if only for one day.

That describes how I felt after seeing myself in Leibovitz's lovely photographs.

The trick is to again capture that lightning in a bottle.

If my financial constraints allowed it, I could hire someone to oversee my lighting on a daily basis, to redo my apartment and mark all the spots that show me to my best advantage, to serve as an advance scout when I'm planning an evening on the town so that I am positioned only in the most flattering seats at the best-lit tables at approved bistros and boites.

Instead, like the proud golfer who produces the scorecard that recorded his day of glory every time he plays with a new foursome, I suppose I should just keep one of these photos on my person at all times. That way, if I meet an attractive woman, at a party or on the subway, who seems not to grasp my greater possibilities, I can present the photo and say, "See? Here, given the right conditions, given just the right lighting and a touch of magic, is what I can look like. It's happened before, and it could happen again. You don't want to miss the chance to experience this transformation firsthand, do you?"

As pitches go, it's a long shot, but what the hell -- I've been on a roll lately.

Shares