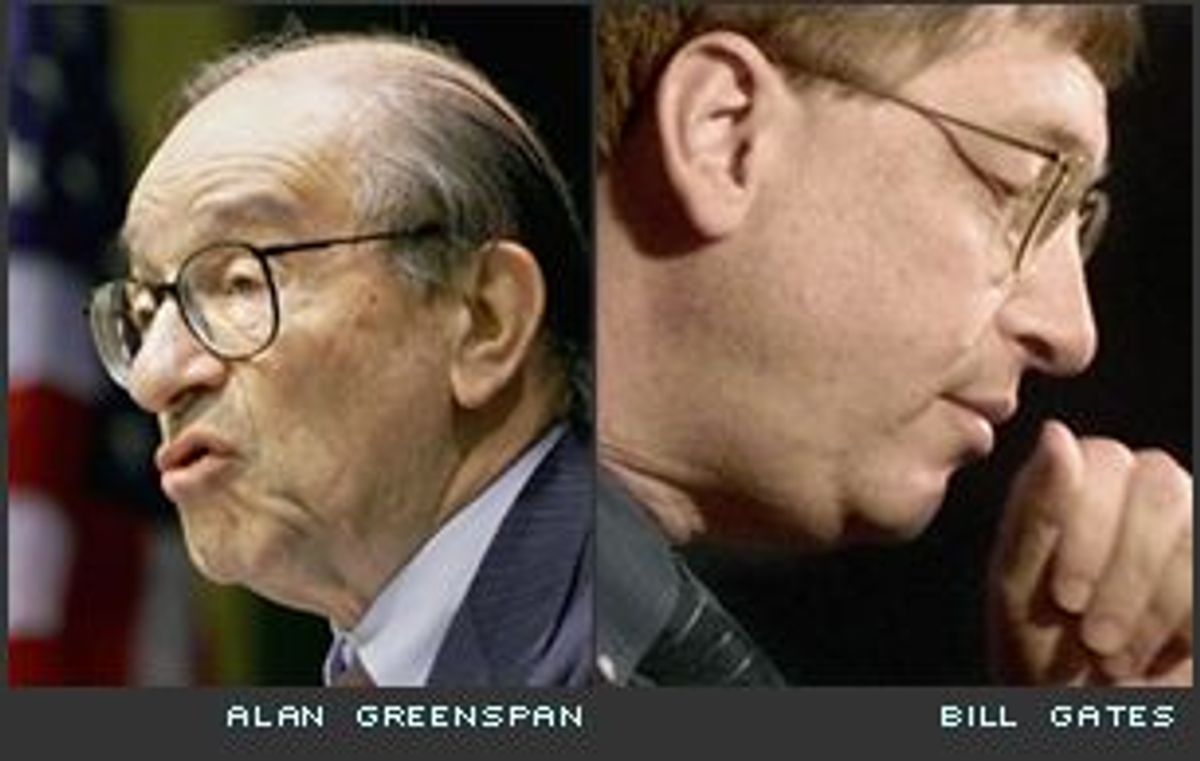

Not long ago, I picked up the New Yorker and found myself deep in a discussion of QWERTY keyboards, network effects and tippy markets; these, said the author, were the key to understanding the digital economy, where a person who controls an important standard can capture an entire industry. Clearly this article was a cultural milestone. When information economics comes to the New Yorker, something has changed in the life of the mind. (The brain reels at the thought of dinner-table conversation between Dorothy Parker and Bill Gates. I've always admired her comment on wealth, myself. "If you want to know what God thinks of money, just look at the people he gave it to.")

We know what to thank for this cultural milestone, of course. It was the Microsoft trial that brought these issues to popular attention. Is the Microsoft decision also the place where they will be resolved, giving us an antitrust law for the information age? Definitely not. Despite the attention given to Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson's ruling this week, we are in danger of missing one of the main lessons the Microsoft trial could teach: that the state is deeply implicated in helping to create the new digital monopolies as well as in trying to subvert them.

The easiest way to understand this point is to think about the continuing debate over antitrust policy. What do we do after the Microsoft case to stop the next monopolist of the information industries? For antitrust skeptics, the answer is "Nothing." We should leave things alone. Let the market work it out. This view is part of a larger intellectual agenda aimed at circumscribing, or perhaps eliminating, the role of the state in the economy. When is state intervention needed? The standard answer used to be that state intervention was needed whenever there was serious, continuing market failure. In a monopolistic market, for example, state intervention may be necessary to restart the beneficial processes of competition.

Over the last 25 years, however, the influential "Chicago School" of lawyers and economists has claimed that this "market-failure" rationale was applied too broadly. In antitrust law, they argued that monopolies may in some cases benefit consumers and that even monopolistic markets can self-correct. The greater the monopoly, goes the argument, the greater the incentive to other firms to find some way to circumvent it. That pressure, in turn, will encourage the market leader to remain lean and nimble. Microsoft must constantly improve quality and service for fear that another company will take away its advantage. If the monopoly continues, it is a sign that the market is working, not failing.

This point of view has no less a supporter than Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan. Back in June 1998, just as the Microsoft case was getting started, Greenspan laid out his ideas during Senate hearings on antitrust and mergers. The hearings have long since been forgotten in the flurry of news about the case, which is a shame. They shed a revealing light on "life after Microsoft." In fact, quite without meaning to, Greenspan's testimony cast real doubt on the current neo-liberal orthodoxy about the state's role in a digital marketplace.

The first surprise was that Greenspan was quite clear about his views on antitrust policy, (to be fair, this is a standard of clarity that equates to the mildly Delphic in an ordinary human being). A close study of his reasoning is worthwhile and not just because he is Greenspan: a man who surely must get a kick out of the thought that at any moment he could leap to his feet in the middle of a boring dinner, shout "irrational exuberance!" and bankrupt three pension funds before his bottom hit the chair again.

Greenspan's words deserve study because his carefully written testimony is the mother lode of the vaguely conservative, loosely monetarist, entirely triumphalist ideology of the neo-liberal marketeer. The stuff is so pure a representation of laissez-faire folk wisdom, it deserves a special name; we should call it Zeitspan, or perhaps Greensgeist.

To hear Greenspan is to hear the people who think they are "the market" talking to themselves, an endlessly reassuring stream of consciousness that returns narcissistically again and again to the self-correcting wonders of market function. (The whole thing is only more ironically delicious when one realizes that one of the country's leading mouthpieces for laissez-faire economics is a state official whose job is to engage in price-fixing: in this case, literally setting the price of money.)

This is not to say that Greenspan is a mere flack; he is actually both conscientious and lucid in his self-assigned role of "economics tutor to the Congress" and his testimony dutifully ran through the basic outline of a Chicago School view of antitrust law. It is precisely that conscientious lucidity which allows us to see the difficulty that neo-liberal antitrust talk has in describing what states actually do in markets, particularly information markets.

Greenspan began by conceding that the people who wrote the antitrust laws, such as Sen. John Sherman, were worried about concentrations of wealth and power. But he quickly turned away from their silly populism to argue that the market itself can provide the cure for inequality.

"This nation has always viewed concentrations of power, whether in government or the private sector, as a threat to individual political freedoms and the equality of opportunity," he explained. "In the public sector we seek democratic institutions and a rule of law to tether excessive political power. In the private sector we encourage competition as the perceived most effective way to contain the undue concentration of power."

Within three sentences he was admonishing those who think that the sheer size of today's monopolies is cause for concern. "Unless a relationship between bigness and market concentration can be more firmly rooted in anti-competitive behavior, bigness, per se, does not appear to be an issue for national economic policy. Rather ... bigness should be primarily the concern of shareholders whose returns could be muted by large-company inefficiencies and their customers who may face bureaucratic inflexibility."

In other words, absent a smoking gun, the only people who should worry about the costs of monopolies are Microsoft's shareholders and customers: the former afraid that Bill might lose his edge, the latter worried that the next version of Windows will be so big it requires them to purchase yet another computer.

The point that "bigness" is not automatically bad seems fair enough, at least if one is willing to see the people that the antitrust laws protect as "consumers" rather than citizens and to see the only goal of antitrust law as the promotion of consumer welfare, narrowly defined.

Indeed, Greenspan's remarks are following a distinguished, rightward-forking path; the move away from concern with "bigness per se" and toward "consumer welfare" marked the first stage of the conservative revolution in antitrust. Thus, in the 1970s and '80s, antitrust policy said goodbye to those, like Sherman, who worried about "[t]he concentration of wealth, money, and property ... threaten[ing] the perpetuity of our institutions."

And Greenspan does not stop there. Even in cases where there is "anti-competitive behavior" he is doubtful that government intervention is necessary to break up monopolies. "I am not saying that dominant positions in industries cannot be maintained for extended periods, but I suspect in free competitive markets that it is possible only if dominance is maintained through cost efficiencies and low prices that competitors have difficulty matching. By the measure of what benefits consumers, such enterprises should not be discouraged."

He was willing to make an exception when the government had helped to create the monopoly in the first place, for example in heavily regulated industries such as banking. But in general, it was clear that he felt the state's legal apparatus should stay out of the market. It should, of course, maintain "a rule of law that protects property rights, both real and intellectual, against force or fraud, enforces contracts and adjudicates the bankrupt. More controversial are the laws that endeavor to improve the workings of the marketplace, the Sherman and Clayton Acts being the most prominent."

In a sentence so well-hedged it verged on topiary, Greenspan admitted that contemporary sentiment was not entirely with him. "More recently, limited avenues for antitrust policy are perceived by some to enhance market efficiencies." He seemed much more comfortable, however, with the thinking of the Chicago School: the belief that "those market imperfections that are not the result of government subsidies, quotas or franchises, would be assuaged by heightened competition."

The obvious exception to this generalization is if the government causes the problem in the first place: For example, by conferring legal monopolies over certain kinds of business as they do in "banking and other regulated industries." But otherwise, one should put one's faith in self-correcting markets. Thus the main role of the state is getting out, and staying out, of the market and then leaving the market to fix itself, which it will do through technological and entrepreneurial dynamism.

This line of argument is not an empty one. In fact, many apparently indestructible monopolies have succumbed to technological change or business innovation. Standard Oil and IBM might have had their monopolies broken without government action. Linux and open-source software really do present a threat to Windows. Gates is not making this threat up, though he is exaggerating its force.

The problem with Greenspan's remarks and the thinking they represent is not their salutary empirical caution, but their analytical blindness. His world is divided into two basic areas. In one, growing smaller by the minute, are those portions of the economy where the government plays a major role in granting "subsidies, quotas and franchises," (and where, as a result, markets cannot be trusted to self-correct.) This portion includes "regulated industries" such as banks. The job of neo-liberal economic thought is to push us toward the privatization of the few areas like this that remain; after all, we know that "state intervention in the economy" is a recipe for disaster.

The second area is an altogether happier place, the realm of well-functioning free markets, where the state does not "regulate," "subsidize" or "franchise" but instead only maintains the "rule of law that protects property rights, both real and intellectual, against force or fraud, enforces contracts and adjudicates the bankrupt." Defining and protecting property rights, we are supposed to think, is an entirely neutral activity, far from the messy, political job of "regulation," or the negative consequences of "subsidies."

But if Greenspan's empirical caution is warranted, this latter part of his argument is just nonsense. It is blind to the ways in which governments shape markets simply by defining and enforcing property rights "both real and intellectual." After all, the distinguishing element of the Microsoft case is that Microsoft starts from a monopoly that rests squarely on its intellectual property rights, its state-backed franchise, over an operating system.

The state is involved in creating such monopolies, because there are choices to be made in designing property systems. Lots of them, in fact. One can agree with the idea that there should be intellectual property rights without answering the question "How far should those rights stretch? What conditions should Microsoft be able to attach to its software licenses? Restraints on competition? On criticism? To get the benefits of the state property grant, should it have to make source code available under a compulsory license? Should it be able to use copyright law to restrict its competitors from making "interoperable" products?"

In the Microsoft case, indeed in almost all of the digital monopoly cases, the dominant company will have to build its strategies around the contours of the original state monopoly we call intellectual property. Expand those rights, and the monopolies form quicker, grow larger. The New Yorker was right about the power of standards. Design the rights more carefully in the first place and the Justice Department may never need to get involved.

When Greenspan conjures up the idea of a market free from intervention, in which the state confines itself to defining and enforcing property rights, he obscures the ways in which the creation, definition and enforcement of property rights is a kind of regulation. In the information economy, where power is likely to be measured in intellectual property rights, the idea that the state is not somehow making choices and picking winners seems particularly obtuse. Neo-liberals should try applying the same skepticism to the process of granting and defining the state-conferred monopolies called intellectual property rights that they do to the state-conferred regulatory monopolies that affect certain kinds of banking business or the electromagnetic spectrum.

I'm not suggesting that we should give up creating and enforcing intellectual property rights; there are often good reasons to support intellectual property rights, just as there are often good reasons to require community reinvestment by banks, or to subsidize access to the Net for poor members of society. But, I don't see how we can segregate these various state interventions in two different categories: the first, a realm of "property law" where we assume benignly that every new right is somehow natural or neutral, that all markets will self-correct and that state actions are immune from the law of unintended consequences; the second a realm of regulation, subsidy and franchise where state interventions are presumed to be losses to welfare, and where markets are so distorted by publicly conferred monopolies that even the Invisible Hand cannot sweep things clean.

Antitrust law is, as its original drafters well understood, one of the techniques that society has evolved to define the permissible limits to dominant power. We now look at antitrust through a narrower economic lens, focusing only on consumer welfare. Like most lenses, this one offers significant benefits and has significant costs. But even if "consumer welfare" were all we cared about, we could not seek it realistically by segregating our analysis of regulation and subsidy on the one hand and our analysis of property rights on the other.

Right now, it is not only Greenspan who seems a little schizophrenic in his analysis of information issues. At the same moment that the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission are trying to restrict the negative consequences of monopoly, the Commerce Department and the Congress are helping to define new intellectual property rights, rights that have a significant potential to create new monopolies. This is the policy equivalent of arm-wrestling with yourself. While one side of the government attempts to ameliorate the last generation of monopolies, the other side of the government hands out the "subsidies, grants and quotas," that will be the foundation for the next generation.

To give one example, Congress is considering a bill, the Collections of Information Anti-Piracy Act, that effectively creates a new right in compilations of fact, a right going far beyond current copyright law. Its critics believe that it would have a powerful chilling effect on free speech and that it could be used to restrict competition in the software and communications industry. (Imagine the monopolies you could create if you were allowed to own some absolutely vital compilation of data: IP addresses on the Internet, say, or gene sequences, or telephone numbers.) Other examples abound: ranging from business method patents, to the anti-circumvention rules from the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

Across the board, intellectual property rights are being dramatically expanded in the belief that this is somehow required by the dynamics of the information age. Viewed from this perspective, Jackson's sweeping factual conclusions, his attempts to armor his decision against appellate review, seem almost quaint. On the other side of town, the intellectual property machine chugs on, granting the guild privileges of the information age.

It would be appropriate, somehow, if it were an antitrust case that made us skeptical of today's land grab in intellectual property. Sherman described the reasoning behind the Sherman Antitrust Act by saying, "They had monopolies and mortmains ... of old, but never before such giants as in our day. You must heed [the public's] appeal or be ready for the socialist, the communist, and the nihilist."

Monopolies or mortmains, (perpetual state-granted property rights). The word comes from the metaphor of the mort main or "dead hand" of property grants, something that deserves more attention as we celebrate the Invisible Hand of markets. Next time he appears before the Senate perhaps Greenspan should pay attention to the mortmains as well as the monopolies.

Shares