Few contemporary filmmakers are as sensitive to revealing the intimate

experience of a character, to exposing the precarious intermingling of souls,

to framing an implacably nuanced world by way of silences and small moments

and a keen attention to detail as Stanley Tucci. In the final scene in his

film "Big Night," Tucci tacitly established a profound reconciliation between

two warring brothers by preparing breakfast, pulling up a chair and placing a hand just lightly on a man's back.

"I find the mundane of the everyday incredibly interesting," the

40-year-old writer-director-actor says about his lyrical new film, "Joe Gould's

Secret." "I think that what we do in our everyday lives is very dramatic --

the intricacies and delicacies involved in our relationships, and how we lie

to ourselves and to each other in subtle ways, and how we tell the truth.

These seemingly mundane things, they have great meaning."

Sipping his tea in a restaurant on New York's Upper West Side, with a violin case balanced against his thigh (he's learning to play for an upcoming role),

Tucci is intelligent, exceptionally warm and vastly curious. He offers up a slew of questions even as he's delineating his own thoughts on a given topic.

An Italian-American brought up in Ketonah, just outside of Manhattan, Tucci

speaks at a rapid, animated clip as he discusses his take on the

state of filmmaking today.

"I believe that plot comes from character as opposed to vice versa.

Those are the films I'm interested in. If plot exists it always becomes

farcical to me," says Tucci, and his movies prove that point. He's much more interested in developing rich characters than in fussing with plot constructs.

Tucci's last Sundance film run was four years ago as the co-writer,

costar and co-director (with Campbell Scott) of "Big Night," the story of a

pair of Italian restaurateur brothers. Tucci describes the open-ended

process of revising this script as "writing and writing for a long, long time."

Then, he says, he met his wife and saw what she was doing: raising two kids by herself

and running a day-care center. "I thought, well, my God, if that woman can

do all that, you can certainly finish this fucking stupid script." The film

went on to be a critical favorite. In 1998 Tucci made "The Impostors," a

slapstick ensemble Beckett-fest about two struggling thespians. Though the

film was panned by critics, it gathered a hefty base of devotees.

"The three films I've made, they all deal with the same theme; even

though they're totally different, the essence of them is the same. In 'Big

Night' it's very much about the creative process and the question of how do

you remain truthful to your art. And 'The Impostors,' for all its

ridiculousness, has exactly that theme running through it. Joe Gould is the

same thing, in that his quest is to be true to his art."

"Joe Gould's Secret," set in a painstakingly re-created 1940s and 1950s Manhattan, is based on the complex real-life relationship

between legendary New Yorker writer Joseph Mitchell and Joe Gould, a

homeless, Harvard-educated man who claimed to be writing "The Oral History of Our Time."

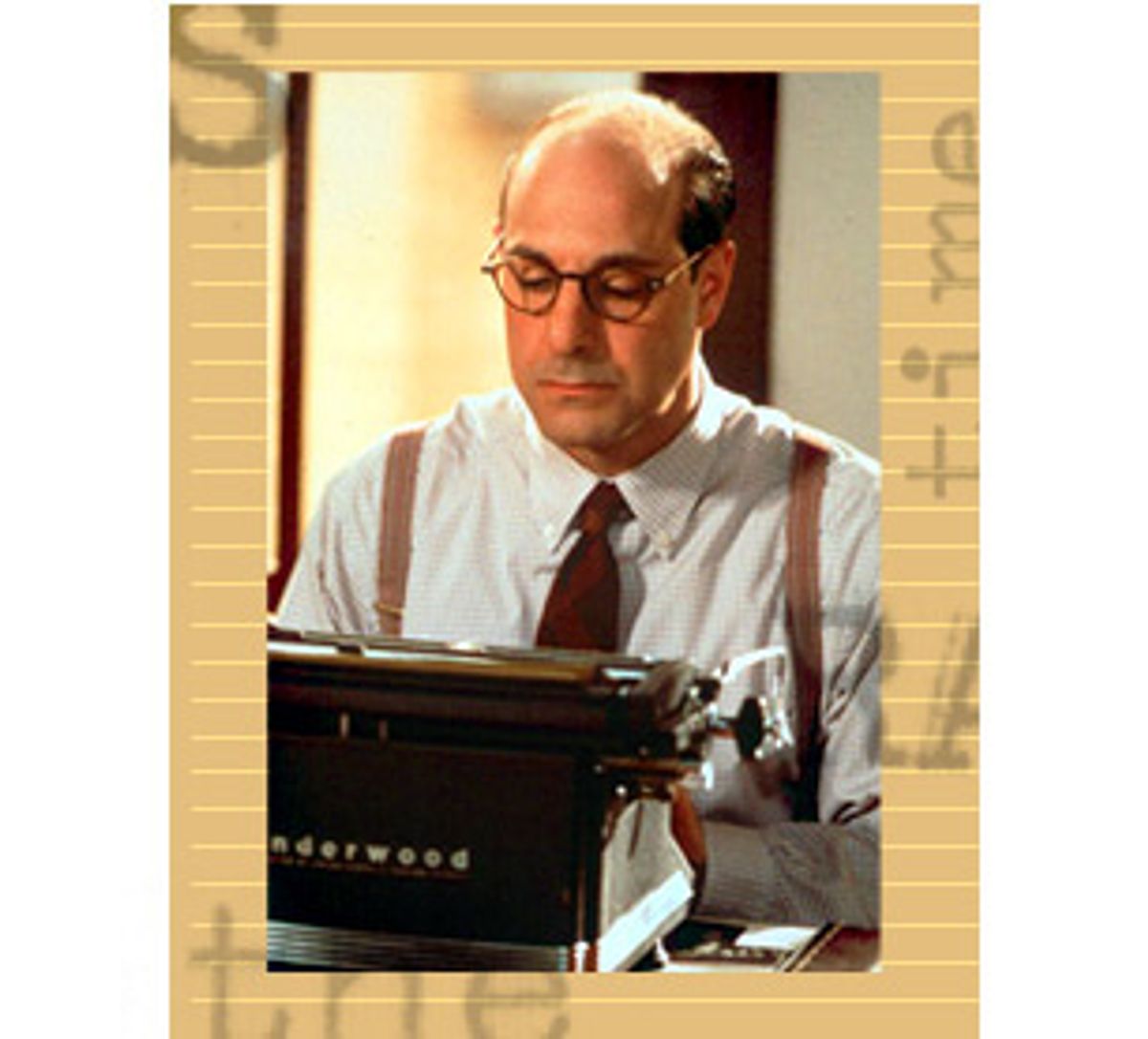

During the course of that relationship, the two men hold fast to a secret that will preserve Gould's honor, becoming shades of one another in the process. Tucci, who costars as the

soft-spoken Mitchell in a deliberately understated performance, has once again chosen a subtle aesthetic form that he hopes will challenge mainstream moviegoers.

The film, which debuted at Sundance to mostly positive reviews, was

slighted by some critics for not having more of a dramatic arc or climax.

"What do they want -- a gunfight, a car chase?" Tucci gibes. "It's just so

silly to me. People have become programmed. We're reduced to actors'

spreading their legs in front of us and pulling down their pants. I mean,

that's how low we've come; that's what we want now. There's no subtlety to

it."

"Joe Gould's Secret" has just such a distinct subtle cadence. The

narrative structure comes from two pieces published in the New Yorker,

written by Mitchell, whose collected writings, "Up in the Old Hotel," had been

tempting Tucci for years before he committed to the project in 1997. He was

inspired by Mitchell's understated approach to storytelling. "Everybody

wants a big story. Mitchell wanted the opposite of a big story. He once

said that the most dramatic event he'd ever witnessed was a woodpecker

pecking away at a tree down South. The more commonplace something was, the

more profound it was. He writes with no judgment and no affectation. He

just tells the story as simply and as truthfully as possible. That's what I

admire; that to me is what I aspire to as a writer-director."

Through the use of scenes played primarily in wide frame and master shots, the film wistfully and beautifully captures the complicated

entanglements of relationships without lapsing into sentimentality. The quiet bleeding over of emotional experience between people of divergent backgrounds finds a framework in the parallels between the courtly, Southern-born Mitchell, who spends his days roaming the streets of the city absorbing the idiosyncratic details of its inhabitants, and his most fascinating and petulant subject, Gould.

Brilliantly played by Ian Holm, who also starred in "Big Night," Gould

is portrayed as a formidable, histrionic, eccentric street person who's often defeated by his own wildly mercurial nature. Gould spends his evenings

visiting with friends such as Ezra Pound and e.e. cummings and frequenting the

famed Raven Poetry Society, charming its patrons into donating to the "Joe

Gould Fund." This officiously titled foundation is ostensibly a means for

Gould to dedicate his life to writing a record of the vocal meandering of

the ordinary folk he encounters in his day-to-day travels. Enormously proud

of an output he estimates at 12 million words, Gould has grandly vowed to

complete his "informal history of the shirt-sleeved multitudes -- what they had

to say about their jobs, love affairs, victuals, sprees, scrapes and

sorrows -- or I'll perish in the attempt."

The itinerant Mitchell is the sort of writer who doesn't hunt for profile-worthy subjects but who still manages to find them at almost every turn. Yet Gould proves an exception, and Mitchell works gingerly to bring the taciturn bohemian into his good graces.

Mitchell initially catches sight of the trembling, scar-ridden Gould in a

Greenwich Village diner as he prepares his lunch by pouring the contents of an entire

bottle of ketchup into a cup of steaming water.

Incited by Gould's

reputation as a profoundly odd, dynamic character and as a man of letters

said to be halfway finished with his nonfiction masterpiece, the journalist

offers up meals and bits of cash before Gould consents to be the subject of a

Mitchell profile. During their conversations, Gould claims to speak sea gull

vernacular -- thus the title of Mitchell's first piece,

"Professor Sea Gull" (published in 1942), which earned Gould a brief period of celebrity. Benefactors would drop by the Minetta bar in the Village, where the scribe

could be seen hunched by the window, beer or whiskey in hand, muttering to

himself and occasionally scrawling in a notepad. And though Mitchell

maintained contact with Gould for months after the article came out, he was

unprepared for the tenaciousness with which Gould clung to him. At that time

he had no intention of following up "Professor Sea Gull" with another piece.

"In New York, especially Greenwich Village, down among the cranks and the

misfits and the one-lungers and the might-have-beens and the would-bes and the

never-wills and the God-knows-whats ... I have always felt at home," said

Gould, who died in 1957. In 1964 Mitchell wrote a revealing two-part article

entitled "Joe Gould's Secret." And though Mitchell lingered on as a staff

writer for the New Yorker for the next 32 years, sealed away in an office and

bound to his typewriter, he never published another piece.

"It's so interesting that 'Joe Gould's Secret' was the final thing

Mitchell wrote," says Tucci. "It's when he finally reveals Gould's secret

that he reveals so much about himself, about how he identified with Gould,

about how similar they were, about how at the end Mitchell was Gould.

"One of the main themes in my films has been the artist as pariah in

American society," Tucci says with a slightly vexed expression. "The

artist's place in our society is always sort of hanging out on this

precipice. Why do we have this awful antagonistic relationship with people in

the arts? Why is the artist always turned into the enemy? It's fucking

bizarre. To be devoted to your art and feel that it is not a luxury -- it is

an absolute necessity to society. It's fascinating to me. Joe Gould had

written something that I put in the script about how people are afraid of the

artist because the artist deals in ambiguity.

"But you know, people don't like ambiguity. I knew I had to make 'Big

Night' because, though I had a perfectly fine career as an actor, I was not

satisfied. I was frustrated working with directors: When I'd watch the final

product of a movie, I felt I was seeing what was happening in American film,

that there was this formula taking over. I wanted to see a film that had an

ambiguous ending."

Tucci says that he wanted "Joe Gould's Secret" to deal with the idea of creativity in our culture, and the film's subtlety seems to underscore his feelings about the way art is viewed in America. "How many naked sculptures are there in New York? None. You might see a

breast here and there," he says, laughing. "But really, no. You'll never see

a penis. Lots of horses, you know, guys on them. How many statues of women? One -- of Eleanor Roosevelt. I mean, where's the sex? Where is it? And then

you look at the Internet and television. It's an adolescent's idea of sex.

Things are ambiguous and dark and sexually provocative, just like your wife

is sometimes. And the artist expresses that stuff freely, and it's

frightening to people."

Tucci's frustrations with the artist's undervalued role in society have become even more personal in his yearlong struggle with the Writers' Guild.

The idea for "Joe Gould's Secret" effectively first came into being six years ago when one of the

film's executive producers, Michael Lieber, persuaded Mitchell, who died in

1996, to agree to a film. Howard Rodman, the film's screenwriter, worked on

the film for a year and a half before Tucci became involved with the project.

When Tucci did commit, it was with the understanding that he would rewrite

the script; he worked on it for four months and estimates that he changed up

to 80 percent of it. When the Writers' Guild, after both an arbitration and

a hearing, refused to give him a shared credit, he was heartbroken. "I know

that because I was both the director and the producer, it was harder for me to get

credit. I know I have to let it go, but it was like the Salem witch trials. They said, 'Can you prove we did anything wrong?' And since everything took

place behind closed doors, I couldn't."

Tucci refers to Rodman, the initial screenwriter, as a "great talent."

But he speaks earnestly about the need for a particular precision in this

script, and about how he was compelled to devote himself to the task of getting it

exactly right, despite the violation of the Writers' Guild rules. "Well, you want

to do him justice," Tucci says about the brainchild behind his film. "If I

can make movies the way Joseph Mitchell wrote profiles, then I could die

happy."

Shares