I know stadiums well. Being the daughter of a football coach (Joe Madden, not John Madden), I grew up in stadiums. On our family vacations to see my grandparents in Leavenworth, Kan., my father would seek out stadiums along the Corn Belt. “Hey folks,” he’d bark, “that’s where the St. Louis Cardinals play!” or “Get your nose out of that book and look alive! This is the home of the Kansas City Chiefs!” We’d clamber out of the car and stand in empty stadium parking lots in the sweltering June sun, squinting at some football monolith.

The only landmark I can recall, other than stadiums, is the St. Louis Arch, but we only saw that from Interstate 70. What was the point of stopping when we could see the arch perfectly from the back seat of our Nash Rambler or Buick?

“Wake up and see the arch!” my mother would yell from the front seat, where she was making peanut butter or Underwood deviled ham sandwiches on her knees. “Who wants mayonnaise? Who doesn’t want grape jelly? Don’t put your feet on the ice chest! Give Clancy a sandwich!” Clancy was our sad-eyed black Lab, who drooled great pools of saliva on our bare legs during those endless trips across the Midwest.

In August, football season began in earnest, although it started for my father in July with two-a-day, which meant football practice twice a day. My brothers attended football camps beginning in elementary school. Often, there were three games a weekend. My younger brother, Duffy, played on Friday nights. My father’s games were on Saturday afternoon, and my youngest brother, Casey, often played on Sunday afternoons. When my sister, Keely, was old enough, she began to cheer at Casey’s games. I was never a cheerleader though I did attend all the games, often with a novel in hand.

My brother Duffy was a jock who loved girls, and most loved him right back. He could talk about all the girls he’d liked from age 3 up, starting with Bethie McCall — they held hands and ate grapes. In first grade, he sliced open his chin on the Iowa ice chasing honey-haired Sheila Walsh. In second grade, he gave Anne Westgate a half-empty bottle of our mother’s perfume. He loved Anne O’Connell, Ann Malone, Becky Morrison, Toni Brungo (he broke up with Toni over the phone before the Super Bowl), Franny Vancheri (he liked Frannie’s older sister, Ellie, too), Patrice Sommers, Erin Doherty. (Erin wrecked his Duster, but he never told and took the blame.)

He liked the prettiest girls in my class too, but I was two years ahead of him, so mostly they were off-limits, which was a huge relief. Still, sometimes girls in my grade would whisper, “Your brother is soooo cute! He can stay and play!” Whenever this happened, he would flash an innocent grin at me, sensing my vitriolic rage at the thought of him hanging around.

Before my brothers were old enough to play football in a league, we would get to my father’s games very early on Saturday and start tailgating. Tailgating in stadium parking lots meant eating peanut butter and jelly sandwiches with other coaches’ kids and our mothers, “the coacheswives.”

My sister grew up thinking “coacheswives” was one word. The coacheswives always had Bloody Marys with limes and fancy swizzle sticks in plastic cups. I loved watching them in their white or black go-go boots, red and gold or purple and white miniskirts, depending on the football team’s colors, high high hair, perfectly red lipstick and thick eyelashes. There was always lots of laughter. The game hadn’t started, so the pressure wasn’t on, and they were finally with adults again after being stuck inside with small children all week.

We moved all the time in search of “the opportunity to win.” I was born in Daytona Beach, Fla., where my father coached high school teams. He got a job at Mississippi State as a graduate assistant, and my mother remembers pushing me down the blistering streets of Starkville and a woman peering into my carriage murmuring, “My, she looks as happy as a dead pig in the sunshine.” Mother also remembers the flea epidemic in the university housing and how folks would leap out of the apartments, slapping their arms and legs.

Next, we moved to Moorhead, Ky., and then on to Wake Forest for Brian Piccolo’s senior year, although my father didn’t coach him. Still, it was information I was able to use to earn the momentary respect of new friends in new football towns — “Yeah, my father knew Brian Piccolo,” especially during the heyday of “Brian’s Song.”

We stayed at Wake Forest for four years, and when I was 6, we moved to Ames, Iowa, where my father was hired as the defensive secondary coach (to coach John Majors) for the Iowa State Cyclones. He coached with Majors off and on for the next 11 years, and gradually I learned that Majors was “John” in the North and “Johnny” in the South.

In Ames, we lived in the Holiday Inn for a month — three kids and our pregnant mother, who cooked beanie-wienies on a skillet in the motel room. I can recall her trying to scrub the skillet under the tiny motel faucet. I don’t remember my father ever being there, except once in a while when he would blow in late at night from the football office. I do remember Duffy playing Tarzan in the motel room by lobbing a belt over the shower curtain rod only to have it come crashing down on him. He needed 10 stitches and my mother needed an extended vacation.

We eventually moved into a house, and a few months after that, my mother went to the hospital to have my sister. When she called the football office to find my father, the secretary said, “I’m sorry, but the defensive coaches are in a meeting. I can send one of the offensive coaches.” My mother screamed, “I don’t want one of the offensive coaches. I want my husband!”

My father finally arrived at the hospital where he found my mother waiting to go into labor and delivery. He looked at her and said, “So, what did we have?’ Her eyes narrowed as she indicated her still very pregnant belly, “What does it look like we had?” Although she had no complications with the birth, she stayed in the hospital for 10 days. She said, “I was happy just to push the juice cart around the maternity ward.”

In our fourth year at Iowa State, the team won enough games to go to the Sun Bowl in El Paso, Texas. Then my father got offered the job as assistant head coach at Kansas State. The head coach was Vince Gibson, whose philosophy was “We gonna weeen!” Coach Gibson had a coaching show on TV where fans sent in crocheted purple pigs, purple wine holders, purple baby blankets, purple tablecloths. After the show each week, Gibson would hold up the items and say, “Now looky here at what purple things we got this week to support the Wildcats! Bless your hearts!”

We lived in Manhattan, Kan., for a year and did not win a lick, so in 1973 my dad reunited with Majors to coach the Pitt Panthers in Pittsburgh.

The moving was hardest of all for me. For years, Casey and Keely, the youngest kids, didn’t notice the difference between one football pit stop and the next. As for Duffy, moving was a breeze. He simply became the new quarterback at the Catholic school wherever we landed, and the girls glommed onto him. He was able to hang out in the locker rooms of the Panthers or Volunteers, be a ball boy, steal roles of Ace bandages and tape.

He also cared deeply about how he looked, and he used to comb his hair constantly until Sister Celine, a cranky Pittsburgh nun, grabbed his comb one day and tossed it in the trash can.

Each moving day, I shot daggers at the movers, loathing them from the core of my soul as they carelessly packed up my beloved room. Finally, my father would shout, “Do you want to stay in the same goddamn town your whole life? What kind of life is that? That’s a bullshit life! Now get your ass in the car!” I grew up with that phrase ringing in my ears, “Get your ass in the car!” I hated leaving my friends in Iowa. Then I hated leaving my friends in Kansas. After each move, when I still had a healthy appetite, my mother said, “You must not be too upset if you can pack it away like that!”

Football intensified more than ever in our lives. I was attending my brothers’ games, my father’s games, and baby-sitting every Saturday night while the coaches and their wives went out to celebrate or commiserate at the bars around Pittsburgh. I never minded baby-sitting, because I loved staying up to watch “The Carol Burnett Show” with my brothers and sister. Then I’d make them go to bed, and I’d stay up for hours after that reading.

At first, I didn’t fit in at any of my new schools. I was taller than anyone in my class, and was often mistaken for a boy because a girl, unless she was a cheerleader or a coacheswife, earned no respect in the world of football, and I really wanted my father’s respect. Hence, I dressed in letter jackets, jeans, high tops, Mexican vests from the Sun Bowl trip. I kept my hair short, and I wore ridiculous octagonal glasses.

Kids would say, “Why don’t you ever wear dresses?” “Are you a guy or a girl?” “Hey Moose! How’s the weather up there?” “You must think you’re so great because your dad is a coach. His team is shit. Pitt is shit!” My pathetic comeback was, “Shut up, jag-off!” a popular turn of phrase in Pittsburgh at the time.

Although Pittsburgh was difficult, by ninth grade, I loved it because I started high school at an all girls’ school called Vincentian. It was not completely girls. They had started letting boys in the year before, but the boys who attended were so insignificant, we didn’t even notice them except to avoid them. I played field hockey, made intense friendships, and then Pitt went to the Sugar Bowl and won the national championship. I even got to meet the Six Million Dollar Man in the hospitality room at the Sugar Bowl.

Since we were winning big time, I felt assured of our place in Pittsburgh. Winning coaches didn’t get fired. Which was true. But they did move on to teams that needed rebuilding, which is what Johnny Majors decided to do by returning to his alma mater, Tennessee.

I was devastated to leave Pittsburgh and go south. Although I looked more like a girl by this time, I certainly didn’t know how I would fit in with the Southern girls. When my parents took me to my first day of school, the priest at Knoxville Catholic High School regaled us with jokes while I sat there stone-faced. When he got up to take a call, my father turned to me and said, “Give the poor bastard a break. He’s told every joke he knows.”

There was no field hockey, and girls played half-court basketball in Knoxville. The students had all been together since the first grade, and they said “Howdy!” A lot. When Duffy started attending the high school with me and playing quarterback again, girls would sidle up and drawl, “Dang, your brother has a cute butt.”

By the time I graduated from high school, my father had moved on again and was coaching special teams for the Detroit Lions. My family moved up to Detroit the summer after my senior year. I went up for a few weeks, but I didn’t move with them because I was set to begin my freshman year at the University of Tennessee in the fall.

Both brothers got on football teams in Detroit, and my sister, Keely, started to get involved with boys and “Godspell.” I went home for Thanksgiving to see the Detroit Lions play on national TV. They went into overtime, and then the other team ran the ball back for a touchdown on a kickoff return. We didn’t have Thanksgiving until three days later.

I gradually stopped watching football. It was like being set free in a way. I no longer had to count the minutes on the scoreboard. I no longer had to pray like hell for Daddy’s team to win. I no longer had to wear ponchos or pantsuits with fringe made by mother in the colors of the team that my father was coaching. (My mother was a true believer in fringe. “If you sew fringe on the bottom, be it curtains or a poncho or pants, you’ll never have to make a hem in your life.”)

Eventually, Duffy stopped playing football, although he played for two years in Division III schools — first at West Georgia in Carrollton and then at Theil College in Pennsylvania. But at 5-foot-10, he just wasn’t big enough. My other brother, Casey, used to grill my father. “Why didn’t you marry someone taller?” (My mother is only 5-foot-2.) “Then I would have been taller! Duffy would have been taller!” I told him, “It doesn’t work that way, idiot!” But he was sure that somehow a taller version of himself and Duffy could have happened if only our father had married a taller woman.

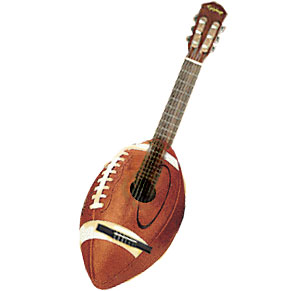

Then Duffy picked up the guitar and started teaching himself how to play by listening to Willie Nelson. My father was hired by the Atlanta Falcons while I was getting a master of fine arts degree in playwriting at Tennessee. (I think I am the only MFA student in playwriting ever from the University of Tennessee.)

After a while, I got married and went to teach English in China with my husband, my dad moved to San Diego to coach with the Chargers, and Duffy moved on to live a songwriter’s life in Nashville, playing at open mikes, studying the blues of Robert Johnson, refinishing and moving pianos with an evangelical, Rick Fretters, who ran “Fretters Piano Services” out of his garage. Duffy also waited tables at the Blue Moon, landscaped and hooked up cable lines.

He had a serious girlfriend, a dog and a life, and then he found flamenco. While channel-surfing one afternoon, he came upon an old Lawrence Welk clip that featured flamenco dancers. Captivated, he sought out lessons. He was hooked, and said, after an early outing on the dance floor, “I smell like I did after football practice.”

At first, we all thought flamenco would be a phase, but we were wrong. My father has sighed more than once over Duffy and flamenco. “He’s 36. A flamenco dancer. My son is a flamenco dancer. What the hell are his job prospects?”

When Duffy first started dancing, flamenco pickings were slim in Tennessee. One teacher had her students perform at happy hour at the Holiday Inn Lounge in Kentucky. Duffy also practiced at a friend’s duplex, but a neighbor came running over and banged on the door, shouting, “Don’t know what you’re doing in there, but you’re knocking pictures off my wall!”

Leaving his girlfriend and dog behind, Duffy studied flamenco in New York for several months. When he ran out of money, he moved in with our parents in San Diego and found a teacher, Juanita, who was into choreographed dances and parades. He danced in the Mardi Gras parade even though only three dancers showed up. Juanita, the teacher, never did get there. From the crowd, a heckler shouted at Duffy, “Hey, Rico Suave!”

Now Duffy pays rent to our parents, teaches guitar and commutes to the San Fernando Valley from San Diego, putting 700 miles a week on his Cabriolet so that he can study with Roberto Amaral, a flamenco master who conducts class behind his Van Nuys carport in a converted garage studio. During heavy rains this winter, the electricity went out, but Roberto lit candles and class continued by candlelight.

I tagged along one night and asked my brother, “Think you’ll ever do this professionally?” He shrugged, “I mostly think about getting the footwork right.” He has no time for a girlfriend. Flamenco and blues guitar are the loves of his life. When he’s not dancing, he’s playing guitar. When he’s not playing guitar, he’s dancing. He’s even learning to play flamenco on the guitar.

I’ve also worked out a deal with him. He spends Wednesday nights at our house in Los Angeles, so he can attend flamenco classes in the Valley on Wednesday and Thursday nights. In exchange, he baby-sits for me on Thursday mornings, so I can get writing done.

He takes our 1-year-old daughter to the park for a few hours. I have watched him amble off with her in the stroller, occasionally doing flamenco steps down the sidewalk. In the afternoons, he might pick up our two older kids at the bus stop, coach them on their piano lessons or challenge them to a pillow fight. It’s really nice having him around.

I have thought about our professions as children of a former football coach. None of us went into sports. My father always did say, “Find something that you love to do and do it!” I am a writer with three children. At age 4, when my son saw his first football game on TV with my father, he’d been watching Charles Laughton in “The Hunchback of Notre Dame,” and was inspired to stuff a pillow into the back of his shirt to create a hump. Notre Dame happened to be playing that day, and he said to my father, “They’re a bunch of Quasimodos, right? Look at their hunchbacks.” My dad said, “Jesus Christ, haven’t you taught this kid anything?”

As for my other siblings, Keely is a playwright and actress in New York, and Casey sells insurance in Chicago. He’s the practical one. He calls us up to make sure we’re saving money. He reminds Duffy to keep paying on his student loan. He calls up my father to discuss stock options.

As I watched Duffy dance recently in flamenco class, I was in a trance. Flamenco means “outside of society.” It’s a dance of the earth, gypsies and blues. In that hot Van Nuys studio, just down the road from a huge Bible and religious accessories warehouse, students from age 9 to 60 danced. I met a criminal lawyer and his librarian wife, who take four classes a week from Amaral. A young brother and sister come down to Van Nuys from Santa Barbara to study.

Beginning with castanets and footwork, Amaral directed the dancers, keeping them “in compass” (in time). The dancers’ hands moved like birds, their feet stomped across the floor. Amaral sang rich, melodious laments and clapped as he called out, “It’s not ‘River Dance,’ people!” One woman whispered to me after class, “When I dance, I feel alive!”

I suddenly remembered my brother spinning our mother around our shag-carpeted living room in Knoxville to “Saturday Night Fever.” My mother shouted, “Your brother has great rhythm! Come dance with us!” Of course, I did no such thing and went up to my room.

My brother plans to leave for Spain shortly. I used to watch him play football. Now I watch him dance.