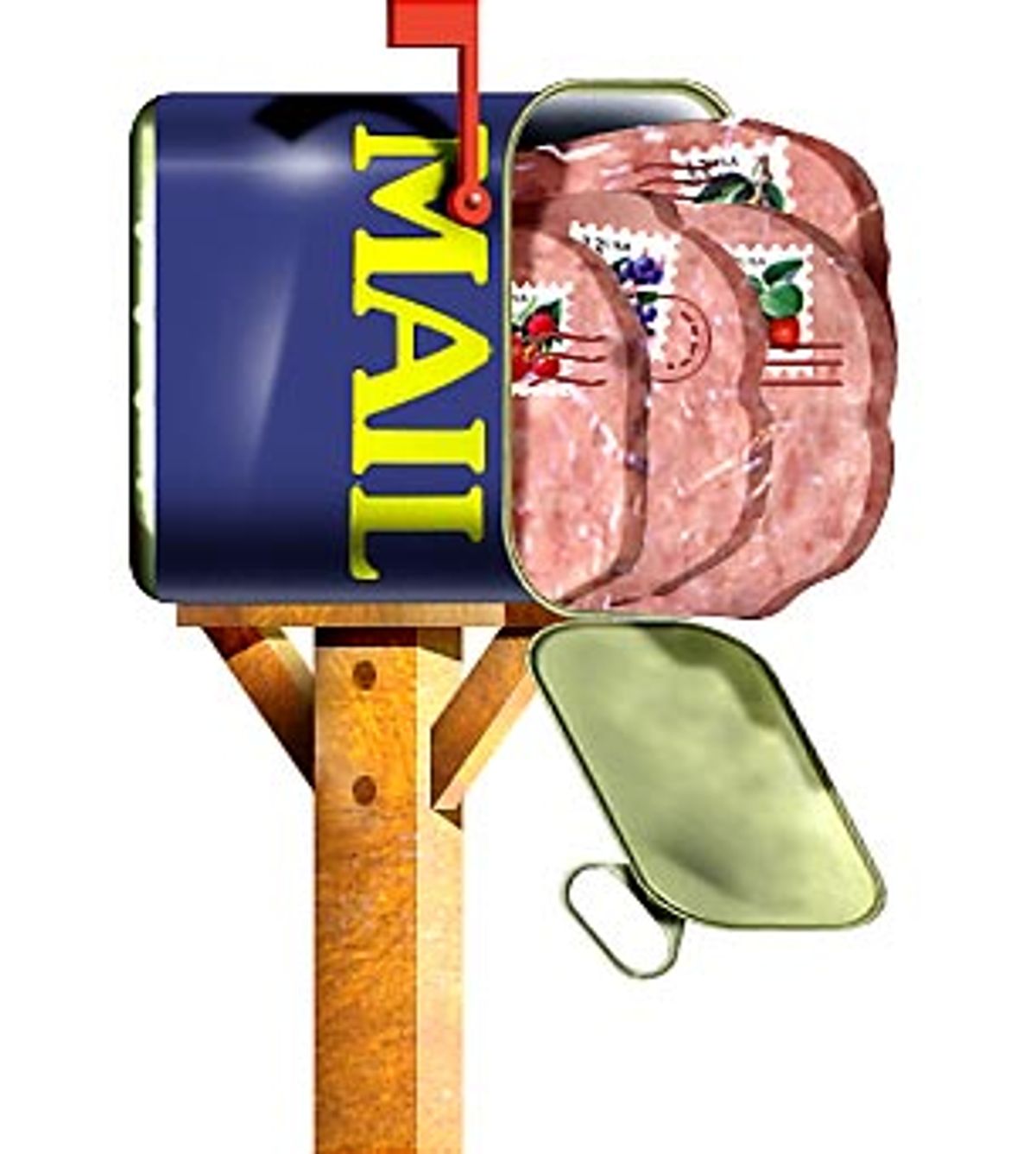

They arrive on your doorstep, unbidden and satisfaction-guaranteed, hawking gadgets and tonics and pills and get-rich-quick schemes. In prose worthy of P.T. Barnum, they try to convince you that you'll make $45,000 in one month, have a sex life comparable with Hugh Hefner's and get a peek at the naked breasts of Pamela Anderson Lee.

Spammers are the snake oil salesman of our generation, traveling hucksters who wend their way across the Net peddling their wares: offbeat inventions and the modern day equivalent of homespun remedies in thick glass bottles. They are out there, invisible, hunched over computers in small towns and big cities, squirreling away addresses like precious gems and firing away enthusiastic missives in the hopes that someone, anyone, will respond.

But the great mystery of spammers is why they load up your in box with their entrepreneurial dreams, but then don't make it easy to buy their advertised wares. Try to respond to the spam and you'll see: There's no one there, no one to sell the products so hyperbolically promoted. The Web sites they so urgently insist that you visit are usually yanked down by the spammers' Internet service providers before you can even click on that highlighted URL; the voice mail at the end of those 800-numbers never seems to elicit a response. Why do spammers bother to send out messages, en masse, if they aren't going to be there to greet their customers? Spam is an even greater waste of bandwidth than you imagine.

Over three weeks I saved my spam; I received exactly 310 spam messages, or about 14 messages a day. Of those, many were repeat messages -- several meandered their way into my in box up to 10 times over the course of three days. You've seen the e-mails, too, I'm sure: "LOSE WEIGHT WHILE YOU SLEEP!!" "Search Engine Secrets Discovered!" and "The Internet Spy Guide." There's "homeworker needed," "$10,000 in 30-45 days," and so on. As the Net has exploded, spam has become as familiar and American as apple pie.

And as the Net expands into new media outlets -- broadband, wireless, portable devices -- you can expect to see even more spam. Just as junk faxes begat e-mail spam, e-mail spam will surely beget wireless spam, cell phone spam, perhaps even interactive TV spam. Already, cell phone owners are starting to receive spam in the form of text messages. Those who subscribe to wireless PDA services, such as Palm.Net, which charge for each downloaded kilobyte, will undoubtedly be incensed when they have to pay to read the 29 kb, 4,900-word multilevel marketing spam "Dream of a LIFETIME!!"

By saving megabytes of mail jammed with precocious samples of entrepreneurial wit, I was hoping to get a sense of what all that spam says. Have I been missing anything by deleting it, unread? And who is sending it to me -- anyone I should know? I spent whole days trying to locate the people behind the spams in my in box. I imagined a grandma in Poughkeepsie selling bulk e-mail software or a slimy salesman hawking illicit Viagra, but finding these supposed salespeople is harder than you'd think.

Think of spam, and your mind probably goes straight to those most obvious, and least prosaic, porn solicitations -- those tantalizing tidbits from "Candy" and "Debbi," so rudely personal that it's almost a shock to open them. "Here is that site you asked for, it's the hottest FREE hardcore you will ever see!!" they say, and it takes me a second every time to register that I didn't, in fact, ask for any free hardcore at all.

But porn is just the tip of the iceberg. If I were to believe this spam I've collected, I can get every pill and drug I've ever wanted, and some I've only imagined. I can visit a Viagra site that will sell me this prescription-only impotence drug with no questions asked, if I'll just read and agree to an extensive "legal" permissions form that waives the spammer's liability for a host of embarrassing side effects. (Four days after I first visited the site, I returned to copy the text, but, like so many other sites advertised in spam, it had been effaced.)

Alternatively, there's something called "America's #1 Natural Super Sex Pill Herbal V," which proffers a roster of sex-crazed clients as proof of its magical ingredients: "athletes, movie stars, retired businessmen, playboys, even a former Olympic basketball coach!" To get the sex life of a retired businessman, apparently, all I have to do is send $29.95. Even better is a spray called Snoreless (the spam generously explains that snoring is "a hoarse, harsh noise made by breathing through the mouth while sleeping"), which I can force my bed partner to ingest. Merely $34.99 for a 60-day supply.

"Cyber Hound 2000" is a racy little software package that will help me find hidden assets and debtors, and investigate my friends and neighbors. ("Everybodies [sic] getting it!" blurts the title, so surely my friends and neighbors are already investigating me.) And there's the "Celebrities Exposed 2000" CD-ROM, which offers nude pictures of Leeza Gibbons and Meryl Streep, among others; "Internet Spy and You," which, I'm guessing, needs no introduction; and the InfoPro CD-ROM, which promises Microsoft's foolproof sales recipe for Internet success, whatever that may be.

Perhaps the most poignant spams are the inventions -- products spawned from toilet-seat epiphanies and household frustrations, hawked by entrepreneurs in far-off countries and housewives hoping to turn their brainstorms into some extra cash. Witness the Phone Cushion, which is marketed by one Tabitha K as "an incredibly soft foam pad that easily attaches to your hard telephone earpiece" that will help me weather those long days on the phone. (Tabitha, however, doesn't respond to my e-mail asking for more information.) There are cable TV descrambler gadgets, and something called the Liquor Gauge which will help ensure that my staff isn't stealing my cognac.

The winner of the most-cheery-spam award: the Enviro Fan, a water-powered bathroom fan sold by an Australian firm. If such environmental concern weren't endearing enough, this spam actually includes emoticon drawings:

\\\\|//// \ ~ ~ / / @ @ \***************************o000--(_)--000o**************************

The vast majority of the spam I sifted through had URLs that were broken -- queer misshapen things like http://3463729345/11.html or http:CDPROMOTION.homestead.com/, which I can tell just by looking at them will lead nowhere. Others offer to sell their products on sites that are yanked by angry ISPs just hours after the spams go out -- many ISPs quickly terminate accounts and shut down Web pages of customers who are spamming. Only a handful of the URLS in the spams I received actually led to active sites.

A lot of spammers don't seem to get the medium at all and want you to print out forms and mail in money to anonymous P.O. boxes or suspicious-sounding companies. Others beg you to e-mail them for more information. I e-mailed 12 of these spammers, but none responded; four of the e-mails eventually bounced back, the accounts abruptly terminated.

Yet other spams -- mostly the get-rich-quick schemes -- want you to call an 800 number and leave a message. First, of course, I have to choose between making $10,000 in 30-45 days, $2,000-$3,000 a week, $46,000 in less than 90 days, $50,000 in 90 days, $20,000 per month or up to $250,000 -- all from companies who fail to explain what, exactly, I'll have to do to earn that money. Oh, the agony of decision! I made five phone calls to this genre of spammers, and only one person returned my call: a rather nice young man at a company that hawks a series of promotional tapes teaching you how to make a fortune. But this gentleman, Chris Orr, when I told him I was actually a reporter rather than a potential sucker, quickly tried to get off the phone. I'd need to talk to his boss, he said.

Still, I wheedled some details from Orr: This was the third e-mail he'd crafted for this product), he said, and the wording he'd used this time seemed to be generating a good response. "There are a lot of people doing bulk e-mail and most of them get not very good responses," he explained when I pressed. "In every business you'll get looky-loos, and your shoppers. So far with us it's a little early, but initial response has been very positive."

He promised his manager would call me to talk some more about how spamming works ("It's free press," I pleaded), but I never heard from him again. Nor did I ever get a response from the other phone calls I made. What shockingly bad business practices -- and a phenomenal waste of bandwidth to boot.

"When you do a postal snail mail direct-mail campaign, you're really happy if you get 2 percent response. Spammers can live with response rates that would put postal direct marketers out of business in a few short weeks," explains John Mozena, co-founder of the Coalition Against Unsolicited Commercial Email. "With an unlimited dial-up account, they can send a few million messages for $20. If they are selling a widget or Viagra, the odds are that they will never deliver anything anyway -- all they want is a credit card or a check," he says.

"If they send out a million messages and only get one response, they've still made their money back plus a bit of profit," he points out. "And if you look at a million people, you'll always find one bone-dumb idiot to send off a credit card number."

The spam industry prefers to call itself the direct e-mail advertising industry, and goes into contortions if you dare suggest that not every single commercial e-mail they send is a fabulous service to recipients. The Direct E-mail Advertisers Association, an organization that purports to be "anti-spam," tells its bulk-mailing members that they should only send e-mail to lists that have been purged of anyone who has complained about bulk e-mail; that they should always include the indicator "ADV" (for "advertisement") in the subject lines; and that they should never mail the same solicitation twice.

But of the 310 bulk e-mails I received, exactly three contained the ADV tag; each of those three landed in my in box more than once. And I've certainly never opted in to any of this crap. Only one contained this informative disclaimer: "This ad is being sent in compliance with senate bill 1618, title 3, section 301.

http://www.senate.gov/~murkowski/comerciale-mail/s771index.html further transmission to you by the sender of this e-mail may be stopped at no cost to you by sending a reply to this e-mail address with the word 'remove' in the subject line."

According to Drow (he goes by one name, "like Madonna or Prince back when he was pronounceable"), a webmaster who maintains the highly subjective Spam Stats page, Extractor Pro is the most popular specialized bulk e-mail software, responsible for a large percentage of the spam that hits your in box.

Extractor Marketing, the company behind the software, is successful enough to have 10 employees on staff and over 1,000 "affiliates" (i.e.: the resellers who also spam you in hopes of getting you to buy Extractor Pro) across the United States. The company was built entirely on e-mail marketing; Extractor sent out up to 10,000 e-mails a week hawking its product. Some 6,000 customers have bought Extractor software, according to Rachel Doletzky, a spokeswoman for the company. So apparently someone responds to the spam in their in boxes.

But who are Extractor's bulk e-mail clients? E-mails Doletzky: "A half-dozen large, Fortune 500 companies, hundreds of well-known business and organizations, hundreds of small to midsized business, International operations, MLM/opportunity seekers, Pastors/Churches, schools, government offices, political candidates, authors, doctors, professors, real estate agents, publications, and so on." (Unfortunately, Doletzky couldn't round up even one of Extractor's clients to talk with me, so none of this could be confirmed.)

What happens when a bulk e-mailer sends out a spam? According to Doletzky, about 25 percent are undeliverable (malformed e-mail addresses, canceled accounts, mailboxes that are too full, etc). Another 25 percent will complain and ask to be removed; 40 percent will get "lost in cyberspace," never to be heard from again. But 10 percent, she says, will respond.

This, of course, comes from a source interested in promoting the merits of her software, and there's no way to confirm the numbers. And why, even when I did respond, did so few of the spammers follow up? Doletzsky has no good answer: merely, "That sounds like plain old bad business to me!"

Despite the difficulties I had finding someone to sell me something -- anything! -- there are apparently those who do purchase what arrives in their in box. Take, for example, the multilevel marketing spam titillatingly titled "as seen on TV," which arrived full of befuddlingly complex calculations and percentages explaining just how much money I, too, would make if I just send off $5 in cash to five different strangers in Texas, Florida and Georgia. This e-mail also came titled, this time, as "Fulfill Your Potential," boasting the exact same text, but five different strangers to mail my money too. And again, the next day, as that "Dream of a LIFETIME." Three new strangers this time, but two -- a Paul Bowen of Florida and Renee Lewis of Ontario -- were firmly lodged at the same position in the hierarchy as the last e-mail. Someone, clearly, had been sending in their money and sending the spam 'round again with their names attached to the bottom.

What mysterious rotations had this spam been making, and who on earth had been so silly as to fill five envelopes with $5 bills and send them off to the strangers' addresses? I shudder for the gullible and weak of wallet who have never seen a spam before (is there such a person, I wonder?) and who take these messages from beyond as personal solicitations.

The most successful spams, I'm guessing, are the ones that are selling spam-tool kits. As Extractor has learned, selling the software itself can be lucrative indeed; there are dozens of spams offering to sell me databases of e-mail addresses and bulk-mail software that will help me mail off my own spam -- for hundreds of dollars a pop. It's ironic that the most tangible products of a spam industry that hawks few real products are the tools themselves. As Mozena notes, "If spam were really a successful business and you were able to make money at it, why would you promote people setting up as competition for you?" And so the cycle begins again.

A hundred years ago, the traveling salesmen who showed up at your doorstep selling their bottled potions and quirky services could be told to go away, and they would, and not come back. Today's

traveling salesmen will, thanks to the wonders of digital media, soon be with us wherever we go -- and we won't be able to get rid of them either. The irony of it all, of course, is that they have

nothing to sell. The dream of a lifetime, indeed.

Shares