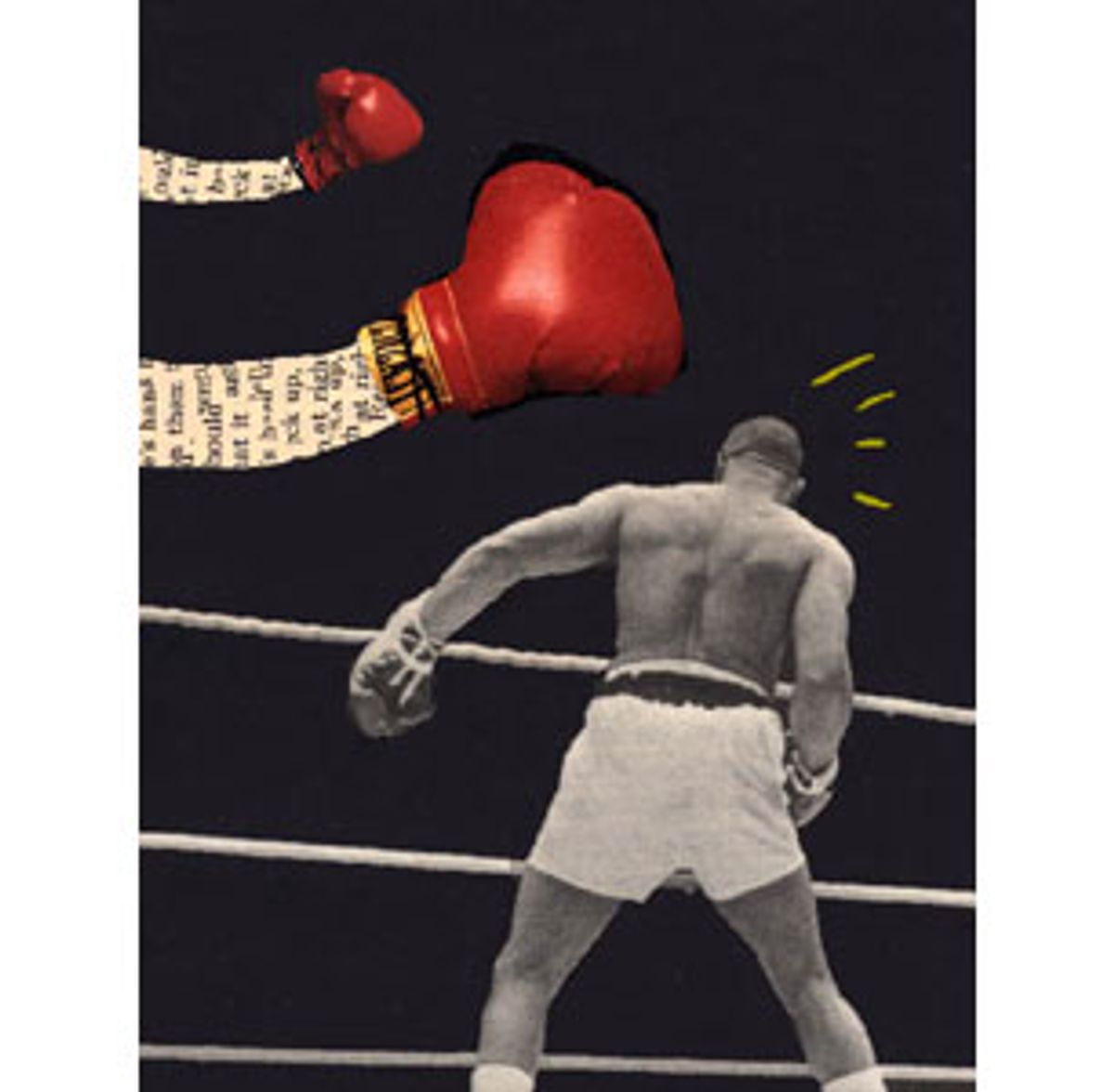

To the list of white journalists who

have underestimated Muhammad Ali we can

now add Nick Tosches. Ali figures

only in the last third of Tosches' "The

Devil and Sonny Liston," but Tosches'

treatment of him says much about the

fantasies that power this book. Here is

Tosches after Ali (then Cassius Clay)

leaps into the ring at the conclusion of

Liston's rematch with Floyd Patterson in

1963:

That rush to the microphone

-- and Clay's career was becoming one

big rush to the microphone -- said much

about the youthful Clay.And, hell, man, fuck youthful: he was 21

years old, a grown man, and it was not

so much youth he was full of but

childishness.A photograph taken before the fight that

night shows Clay in a checkered sport

jacket, eyes bulging, mouth open and as

wide as the Holland Tunnel, screaming

his praise for himself, while

entertained white onlookers

smile.

You have to hand it to Tosches: He may

not be the first writer to turn himself

into a goddamned fool by dismissing Ali,

but at least he finds an original way to

do it -- and it would take someone

highly original to paint Ali as a

cartoon darky making the white man

smile.

It goes on:

He was, at this point in his

career, seen as an audacious but

enamouring child, a frivolity of the

noble white man ... His sense of humor

... was not much developed beyond the

playground realm ... His tiresome and

trying wit, his harmless and drably

colorful shows of playfulness, and his

affected audacity were perfectly suited

for the media of the day ... Clay should

be regarded as the first made-for-TV

boxing idol. As he danced and cavorted

in acceptable and inoffensive

outrageousness before the masses and the

cameras and the microphones of

mediocrity, so mediocrity embraced

him.

Bullshit. Tosches allots a single

sentence to the thrill that a proud

young black man who wouldn't play humble

gave African-Americans in the early

'60s. His claims that Clay was a court

jester to the white middle class are

laughable to anyone who remembers the

suspicion and hatred Clay aroused even

before he converted to Islam and defied

the draft. In a country undergoing a

defining struggle with racism, how could

the reaction to a boasting black

loudmouth be any different?

Tosches writes about the fear that

Liston's 1962 fight with then-champ

Patterson aroused in black

America. The soft-spoken, insecure

Patterson (the subject of the most

moving section of David Remnick's Ali

book, "King of the World," was a role

model, while Liston -- mean outside the

ring, vicious inside it and mobbed up on

top of that -- was someone most black

Americans considered the opposite.

Tosches doesn't address the dilemma that

a Liston-Clay match posed for blacks,

who, all too conscious of white opinion,

felt they were being forced to choose

between a thug and a braggart. Nor does

he cite any of the racist ridicule

that such established sportswriters as

Jimmy Cannon and Red Smith directed at

Clay. What accounts for Ali's appeal, in

Tosches' view, was his ability to play,

for white writers, "the dream cards of

manliness, racial understanding,

provocative sensibility and bond between

writer and warrior."

The key to Tosches' attitude lies in his

dismissal of Ali's fans in the press as

people "who could write no better than

they could fight." In much the same way

that Albert Goldman's "Ladies and

Gentlemen: Lenny Bruce!!" was a

performance designed to show off the

author's hip credentials, "The Devil and

Sonny Liston" is designed to demonstrate

that Tosches is fit to walk in the

shadow of the King Motherfucker himself.

While Liston demolishes opponents with

the brutality of his blows, Tosches goes

down the mean streets of professional

boxing, ventures into the shadowy

corners of mob dealings and dares to

reveal the fixed fights. He wants to be

on the page what Liston was in the ring:

the man who will not be fucked with.

But a biographer who aims to be a

mythmaker may wind up dealing in

inflated pulp archetypes. Tosches turns

Liston into a white writer's fantasy of

black rage. Where his Jerry Lee Lewis

biography, "Hellfire," was a mythic

battle between sin and salvation for his

subject's soul, this book is a story of

the devil triumphant. To Tosches, Liston

is the walking embodiment of bad voodoo,

"the big bad nigger who looked at you

like he didn't know whether to drink

your blood or spit on you, or, worse,

like he didn't even see you with those

deep dark grave-dirt-colored dead man's

eyes of his; the big bad nigger who come

up here from way down there and took

people round the neck from behind like a

beast."

Granted, Tosches is a remarkable

reporter. He digs up hangers-on and

fixers and flunkies who you would have

thought had gone the way of sharkskin

suits. But I couldn't keep straight the

promoters and the mobsters who populate

these pages, or sort out their deals and

their double-crosses. After a while, I

wasn't sure if it mattered. Like Martin

Scorsese's "Goodfellas," "The Devil and

Sonny Liston" is high on the big-balled

braggadocio of hoods and mobsters.

Scorsese got by with his adolescent

fascination through sheer energy. Bogged

down in the swamp of literary pulp,

Tosches sinks.

And though he has a reporter's

instincts, he doesn't have a reporter's

discernment. In one section, Chicago

attorney Truman K. Gibson (who helped

Joe Louis out of the financial morass of

his later years) tells Tosches that in

his years in boxing he knew of three

fixed fights. Tosches names two and then

demurs: "As for the third fix, I doubt

if history and the lawyers that stand

between these words and my paycheck are

ready for that one." That's a tabloid

tease -- a shocker too hot to reveal.

But what prevents him? Either he has the

evidence to back up his claim or he

doesn't.

It's in the allegation that Liston's two

fights with Ali were fixed that Tosches'

judgment is most in question, though.

He's hardly the first person to make

that claim. In the first fight, Liston

simply refused to come out of his corner

for the seventh round. In the second,

Ali's right felled Liston in the first

round. If these were fixes, they were

spectacularly obvious ones. Tosches

makes a good case that a man of Liston's

temperament would make a fix

obvious out of plain resentment. And he

includes the assertions of Liston

associates that Liston said he threw the

first fight.

But whatever the truth is, the way he

calls the fights themselves feels off the

mark. Ever eager to diminish Ali, he

insists the boxer was faking when he

claimed temporary blindness in the fifth

round. (Liniment applied to a cut under

Liston's eyes had gotten onto Liston's

gloves and into Ali's eyes.) But A.J.

Liebling, whose writing on boxing is

among the best, claimed that the best

fighter he ever saw was Pete Herman, who

had been nearly blind at the time

Liebling saw him fight. (Among other

things, Herman would move his head to

draw punches and determine his

opponent's position from where the blows

passed him.)

Tosches claims that the "phantom punch"

(as it's come to be known) of the second

fight was "a blow so slight that few

could see it." Really? A few years ago,

at the Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota,

N.Y., my wife and I took in a

documentary on Liston. When it got to

the rematch with Ali and the "phantom

punch" (recorded by one camera), I heard

my wife gasp, and when the punch was

rerun in slow motion, I could see

Liston's neck snap back and his head

crumple onto his right shoulder as the

rest of him followed suit all the way to

the canvas.

In fairness, Tosches is careful to point

out that the victors of fixed fights are

never in on the fix. (It has to look

believable.) But even if Ali became

champ through a fix, somehow he stayed

champ -- and that's territory into which

Tosches doesn't venture. Joyce Carol Oates has observed

that after the government deprived Ali

of his peak fighting years, he came back

to discover that while his youthful

speed was gone, he could take a punch.

If the older Ali could withstand the

blows of George Foreman -- a fighter who

was probably the equal of Liston in the

power of his punch -- couldn't a younger

Ali have withstood the blows of Liston?

Ali's triumphant strategy in Zaire in

1974 was to let Foreman punch himself

out and then move in to finish him off.

Couldn't he have worn down Liston in the

same manner?

Tosches knows there's a great story

here. And we may get it in the upcoming

film in which Ving Rhames is slated to

play Liston. But his tough-guy stance

and his slumming infatuation with sleaze

get in the way. He knows how to sort

through rumor, making a convincing case

that Liston's death in 1970 (apparently

from a heroin overdose) wasn't the mob

hit it's been claimed to be. But he's

not above allowing rumor to advance his

view.

The contradictions of Liston are

worth exploring. But have we traveled

much beyond the sentimentality of that

old boxing weepie "The Champ" when

Tosches tells us that Liston was kind to

children or that one of the mourners at

his funeral was his adopted son? Tosches

comes across, finally, as one more

stunned child mourning a fallen idol,

his prose the embarrassing result of a

childish fantasy that has been pumped up

to convince us of its manly resistance

to fantasy.

Shares