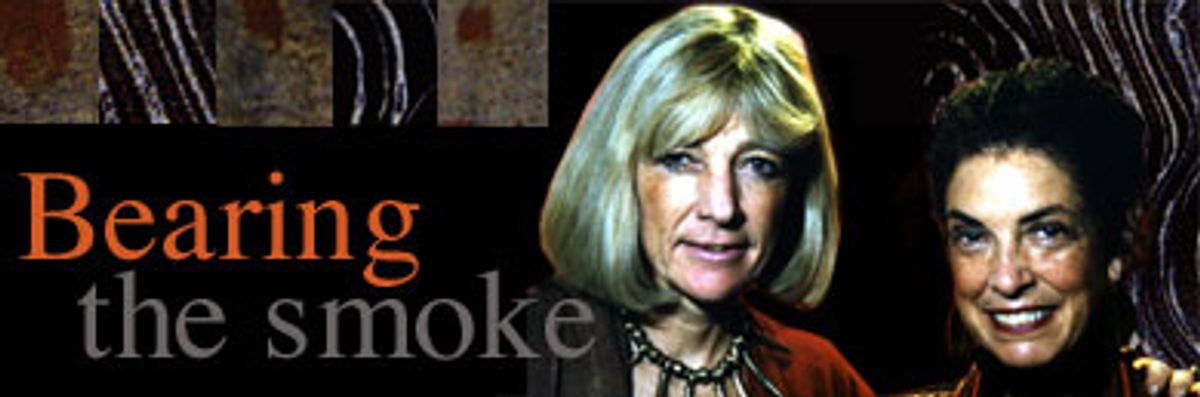

When Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher, the photographer-authors behind "African Ceremonies," came to the Salon offices to be interviewed, heads turned as they walked past the cubicles. This was partly because of the eye-catching clothing and accouterments they were wearing -- elegant, flowing African robes in deep, earthy reds and browns and golds, plus pendulous golden necklaces, earrings and bracelets. But it was also, I think, because of the air they exuded -- a mind-catching combination of passion, theatricality and humility.

In the ensuing hour, as their words transported us back to an Africa we all love, I was filled with inspiration and admiration for these women -- Beckwith, an American graduate of the Boston Museum School of Fine Arts, and Fisher, an Australian-born social-science graduate of Adelaide University -- who had had the sensitivity, intelligence and persistence to glimpse the African soul and, even more amazing, gain an intimate access to that soul as no other foreigners ever had. And I felt a profound gratitude that they had chosen to offer up these glimpses in a sumptuous celebration that all of us can share -- and that will enrich our lives and the lives of generations to come, around the globe.

A major exhibition of photographs from "African Ceremonies" will open at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York on July 14 and run through Sept. 27. The book is available at most bookstores and through online booksellers.

"African Ceremonies" is such a monumental work. How did you originally come up with the idea for the book?

Beckwith: Carol and I both had a dream that we wanted to record all the ancient ceremonies and cultures in Africa, across the continent, before these wonderful traditions disappear. We had just finished a book called "African Ark," which was a five-year collaboration about the Horn of Africa, and people said to us, "Are you going to do another book?" and we looked at each other and thought, "This is the moment to start."

"African Ceremonies" was a 10-year project. The first year was taken raising funds in America to cover the fieldwork. We really wanted to tell a story in Africa that goes into every kind of passage in life that people take: the transition from birth to initiation, then from courtship to marriage and then finally into adult life and gaining richness. Then we did a series of communal ceremonies that included seasonal ceremonies, and ceremonies of religious beliefs and healing, and the final passage of life, which is the passage of death and the passage into the afterworld -- the world that many Africans actually view as greater than the world that we're in today.

How did you plan such an ambitious project?

Fisher: We actually put up a very large pegboard around the room, and we would pin up ceremonies that we knew existed, according to the months. We had January through to December on the pegboard, and we would say to ourselves, "Right, we know that the traversing of the Niger River in Mali is something that happens in December, and the great cattle crossings are December to January," so we'd make a little mark there.

We put everything we could possibly think of onto that board and then we started researching and finding out the ceremonies that, say, happen every 12 years -- could we get that into this period? Or could we get, say, a Masai passage from warriorhood to elderhood, which is once every seven years in Kenya, onto the board? And we made a kind of organizational plan where if a ceremony happened only once every year or once every several years, that ceremony got priority. And then we would map out year by year.

It sounds very organized, but Africa is completely different from that, so what we would find is that we'd set off with a plan to record a king's 25th anniversary, let's say. That was a set date, so we could record that, and then we thought we would go on to do a fantasy coffin funeral -- and we'd find that there wasn't one at the moment, but there was something else happening with voodoo on the border of Ghana and Togo. So suddenly we were off to record that. We really kept our eyes open and asked a lot of questions, and sometimes got some of the best ceremonies completely unexpectedly off the backs of ones we'd already planned. Eventually, we spent six to seven months a year -- not all in one visit but in several visits per year -- for the 10 years to record the ceremonies, and learned a lot through the process.

So the book was organically growing as you were in the field, finding out about new ceremonies?

Beckwith: Yes, we initially thought that the book would take us three to four years. After three to four years, we realized that if we could achieve this coverage in 10 years, it would be fantastic. At the end of 10 years, we had over 200,000 images, which had to be edited down to the best 850. We had the most intense year of editing images, of deciding which ceremonies represented a category, how to give the expanse of the whole continent showing the richness and diversity of it, how to contrast one side with the other in terms of marriage rituals and the like.

And there were so many surprises along the way.

For example, we taught our great nomad chief friend, Mokao, in the Sahara Desert to write in Fulfulde. If a major ceremony was happening, he would write a letter phonetically in Fulfulde, send it with a camel rider in the nearest town and get it posted to us. We would have to leave London on 24 hours' notice in response to these very special invitations from across the globe. Sometimes we would arrive and learn that the ceremony had been postponed for six weeks, and Mokao would say to us, "We have a wise Wodaabe proverb: She who cannot bear the smoke will never get to the fire." And that became our motto for having patience over the course of our fieldwork.

How did you get access to so many of the ceremonies, some of which had never been photographed or even witnessed by outsiders before?

Fisher: Both of us have been passionately involved with traditional Africa for 30 years each, and we have made very strong friends in different communities across the continent; we see every visit as a visit into a new community where we are going to become a part of that community. By the time we came to doing "African Ceremonies," we had become connected with certain families who really wanted us to record things. Also, when people realized how dedicated we were to something, they would say, "Have you heard that the Bella people, who have worked with the Tuareg, also do a very interesting part in the Cure Salee ceremony? Or this is a time when all the camel people come together, and they're looking for a salt cure from the ground, and you'll get a mixture of Tuareg, Wodaabe and Bella people all at once."

We had spent enough time to really win people's confidence, and we also believed that whenever we did anything in Africa, we should always repay in a way that was appropriate. Sometimes people really needed wells being dug for them, and sometimes people really needed millet to be carried into a village, or sometimes people just wanted personal razor blades for haircutting and fishing hooks. That kind of community made doing this book possible, because people let us into things that other visitors would never see.

Clearly you have a very deep-seated respect for the local cultures and the people you encountered along the way. They must have sensed that respect and sensitivity on your part, and probably opened up to you in a way that they wouldn't normally open up to outsiders.

Beckwith: We entered very slowly into villages. We would come in, we would meet the village chiefs, we would sit under an acacia tree, getting to know the chief and his family. We'd learn 50 words of every language group before we went in -- we'd usually write them on our hands so we wouldn't have to pull notes out and could be more spontaneous -- and just the effort to learn 50 words was so appreciated. We could greet people properly, we could thank them, we could ask basic questions. It was only when we really got to know the chief and his family in the village that we would pull out our cameras, because they would understand then what we wanted to do, and would have agreed to allow us to be there. Our goal was to be as invisible as possible. And when we finished our work -- because as Angela said, there's such a wonderful principle of reciprocity in Africa -- we would usually sit with the elders and say, "How is life for you and what do you need?" And our goal wasn't to give them something that would depend on us to maintain but, rather, to help them with something that they could have for themselves, totally apart from us.

So sometimes it was needing water from a well, and sometimes it was, as in the case of the Masai, "Could you help us to start the very first all-Masai primary school?" And we would say, "Why do you need this?" -- because they were so resistant to sending their children to school -- and they would say to us, "The government is forcing us to send our children to school and we're sending them out to Kikuyu schools; they're learning about agriculture and they're coming home ashamed of being traditional pastoral people and thinking that they're being 'primitive.' We want our children to be proud of who they are and, if they must enter the 20th century, to enter with their values intact and with a sense of how pastoralism can survive and enhance the country. So we would like to teach our children with Masai teachers and Masai textbooks." We got very involved in this project and helped start the first all-Masai primary school on the border of Kenya and Tanzania. Our feeling always was to give back and honor all that people had given us to make our work possible.

And by doing that, you became woven into these people's lives.

Beckwith: For years and visit after visit. We visited the different groups many times.

How many different groups did you actually visit?

Fisher: Probably about 45 different groups. The interesting thing is that our photographs became far more interesting after our third or fourth visit. We'd look at them and think, "Isn't that fascinating, that we knew exactly where to take that photograph from?" or "That photograph of so-and-so is much better; he's really relaxed with us." There's just an area where you realize that familiarity and trust in photography -- as well as, for us, familiarity with what's happening in a ceremony -- are important. If you can see a ceremony twice, you can actually think: That whole group is going to go down to the chalk cliff and paint their bodies and go through the forest; we'd be better off in this position if we can possibly get access.

So for days in advance we could ask the elders, "Would it possible for us to go into the forest and take the chalk cliff?" It's just a feeling of pre-guessing things, as well as having people feel very comfortable with you. We would hang out with them 24 hours a day, and some of the nicest photographs would just be taken very casually, when you'd just suddenly think, "Doesn't she look wonderful? I want to take her picture. She's just doing her thing."

Beckwith: What was really delightful was that the longer we stayed with people, the more the women would want us to transform to look like them. With the desert nomads in Niger, for example, after a few months, they said, "To tell you the truth, we don't actually like the clothing that you wear, and your hairstyles aren't very fashionable. Could we tress your hair, or could we dress you properly?" And so pretty soon we were wearing embroidered wrappers and little tunics, and our hairs were in many braids, and they'd say, "We know you may not want to be scarified, but can we draw little patterns on your cheeks so you have our designs, and put head wraps on you?" And pretty soon, we were looking just like the desert nomad women, and they were so much happier with us.

The difficulty came when we'd be sitting with the women sharing intimacies and suddenly the men would start doing something absolutely amazing, and we really needed to be photographing it, but we couldn't leap up because we'd become honorary women.

So Angela and I realized that if we put on our camera jackets and trousers, we would suddenly become genderless again. People would say, "Oh, yes, now they're outsiders, with their camera jackets and trousers; they're half-men and half-women." Then it was fine with everyone if we jumped up and ran off and photographed the men.

As long as you changed your clothes.

Beckwith: Yes, as long as we changed our clothes. Because in Africa, what people wear, whether it's clothing or adornment or jewelry, tells the story of where they are in life, their status, whether they're married or unmarried, whether they have to behave in a certain modest way or whether they can be a bit more aggressive. So the story and statement of our clothing and jewelry, whether we were them or foreigners, allowed us a certain curious freedom as photographers. We were very lucky because we were given incredible access to both male and female worlds, which we could never have had if we had come in as men, who would not have been allowed to penetrate a female world. We couldn't believe how we had luck and access and invitation to photograph some of the most intimate ceremonies of the males.

Can you think of one in particular?

Fisher: We did one circumcision with the Teneka in Benin that I don't think any outsider has photographed before. This circumcision, which happens at about 27 years of age, is very grueling for a young man. They go through many days and weeks of ritual building up the courage to do this. We were not only allowed into that area, we were sort of taken in as part of the community. We went through every single ritual with them; we even witnessed the elders, who have a special dance where they hug the man who's about to be circumcised. They would hug him around the chest as they danced, and they were actually listening to the pulse of his heart. If they felt his heart was racing too hard, they would give him very quietly -- and not seen by the rest of the community -- a special herb that would calm him down so he would be able to face the next few days and the challenge of initiation and circumcision. These are the kind of secrets that you learn.

Is there a woman's ceremony that stands out in your mind?

Beckwith: Among the Krobo people, who live in eastern Ghana, there is a very beautiful and poignant initiation ceremony that takes place each year. During a three-week period, an entire generation of young girls makes the transition to womanhood, which is something very different from what we know in the West. During this period, they learn the domestic arts, they learn the cultural arts of music and dance, they learn the arts of female beautification and they even learn the arts of seduction. One of the striking rituals of this is that the young girls are led by their ritual mothers at the climax of the ceremony into a sacred forest, where they undergo a test of their virginity. Each girl is lowered onto a sacred stone from Krobo Mountain, which is the place of their origin. As her buttocks touch the stone the priestesses study her belly. If her belly remains calm, they say she's a virgin; but if her belly trembles, it means that she is not a virgin. In the olden days, she would have been thrown off Krobo Mountain, but today her family is heavily fined. At the end of this ceremony, where the girls have been taught by ritual mothers -- not their real mothers but mentors whom they have for life -- all that is necessary to enter womanhood, the girls are presented at a ceremony to the community, to family and above all to potential suitors. It's a beautiful ceremony. It takes place with grace, delicacy and refinement, and the girls are considered to be among the most desirable wives in all of West Africa.

Were there any circumstances where you felt emotionally conflicted or ethically conflicted? Where a ceremony you were photographing was in some way troublesome to you?

Beckwith: I think that in Muslim societies we sometimes met resistance to ceremonies being photographed. The fathers or the brothers of the women felt that they didn't want their women photographed, that they didn't want any of these pictures published. We were very sympathetic and we understood this and we always asked for permission to photograph, and if they said no, we respected it. But sometimes with time and with an understanding of the project, the noes would turn into yeses. I remember on Lamu Island, off the coast of Kenya in the Indian Ocean, we spent many years with one family, who finally said, "Yes, you may photograph my daughter, but she must be covered with the bui-bui, a black veil -- only her eyes will show -- and you have to take her in this little corner of the rooftop in order to have natural light with three corners shielding her from the eyes of the town."

And we did. We took the picture. And it was a beautiful picture because the expression of who she was and everything she stood for came through her eyes. She was trying to say to us, I think, "I know I can't show any more, but I'm going to tell you everything." And of course her hands were also beautifully painted for the photograph, so this is really a portrait of a woman expressing her inner being through her eyes and her hands, and it came out of a great patience and respect for the resistance and, in time, the no turning into the yes.

Do you remember the moment when the no turned into a yes?

Beckwith: It was terrifying because we thought, "What if we blow this?" We had this one chance to take this picture and thought, "What if our exposure's not right? We know that they'll give us about five minutes to do it -- what if we don't load the camera right?"

I remember once, and thank God it only happened once, we loaded the camera and the film didn't catch on the sprocket, and we spent the whole day in the Sahara Desert with desert nomads, photographing a most wonderful ceremony. At the end of the day, we unrolled the film and suddenly realized what had happened, and we went into a total sulk. We went off to the corner of the nomad camp and looked so gloomy and blue that the nomads came over and said, "What's wrong with you?" When you're in nomad society, you're expected to be present and social all the time. We explained what had happened, and they said, "Oh, that's absolutely nothing; we'll do everything for you tomorrow that we did today, so start smiling again and come join us."

Fisher: The first trip we did with the Wodaabe was really extraordinary because it so typified their motto: "She who can't bear the smoke will never see the fire." Carol and I had decided to meet in Niger, in the capital. We flew in within three hours of each other, not knowing what flights we were on, waited for each other and took our bags and our little cameras and went down to the truck depot in the town, caught a truck -- and within six hours we were in the desert in a town called Abalak. In Abalak we knew that if we got off the truck we would actually meet some of the Wodaabe people who were coming into the market, because we had researched market days and Friday was market day in Abalak. So we literally had just arrived, on the back of a truck, got off at the market and walked around the market to find the Wodaabe corner. We found a chief who was called Hasan, and we said to him, "We have come to photograph the annual Geerewol ceremony where men do beauty dances to attract wives, and we're serious, we really would love to record it." And he said, "Absolutely, would you like to come with our family?"

It all happened so very quickly. "What you need to do," he said, "if you've got the money, is buy yourself a donkey and put the luggage on the back of the donkey, and then you're free to walk." So he helped us buy a donkey, and then that night we left the market with the nomads, with our little belongings on top of the donkey.

Six weeks later, we were still walking with the nomads. No ceremony had begun. And what was remarkable was that we actually learned at this stage that we were becoming very bonded to the family, and we knew that through this something very special would happen to our lives. Every day was very enjoyable; we walked about 10 kilometers [6.2 miles] a day in the midday sun -- I don't know why they walk in the midday sun, but they do -- and we actually managed to live off a calabash of milk a day. We didn't have other food with us at all and we were in the middle of the desert.

After about four weeks we looked at each other and thought, "We don't look bad! We really look healthy! In fact, we look the best we've ever looked!" And we realized that we were very lucky, as the two of us obviously have an enzyme inside the body that allows us to break down milk, which many Western people don't have. But we, like the Wodaabe, could get complete nourishment from just eating and drinking fresh milk from a calabash. And after six weeks, sure enough, the ceremony started, and we were the only outsiders to be there.

Beckwith: When the ceremony was over, the chief who had been our host came to bid farewell to us. It was so difficult to leave because we had become so close emotionally to these people. And I had managed to learn their language over a period of time, so that eliminated the need for an outside translator. When we came to leave, the chief came running behind us, scooping up sand from our footsteps, and he took this sand and he put it into a little leather talisman pouch over his heart, and said to us, "If I wear your footsteps over my heart, I know that in this way you'll return to me again." We've been back about 15 times since then to visit those Wodaabe nomads.

Looking back at your books and at all the years you've been doing this, what do you feel you've learned from Africa -- what have you taken away from the continent?

Fisher: We've realized that the ancient cultures of Africa, the still-whole belief systems, are very important in life. We've realized that one of the most important things is the passing on of knowledge from one generation to another, the benefit of elders in a community, where you can really learn from people who have lived and experienced and who can guide you through life. Another thing is that in photographing some of the initiation rites and the rites of marriage and courtship, we've realized how important it is that people have the chance to go through life being trained at each stage for the next situation in life: You don't go in blind to your next role; you go in with a feeling of confidence in your ability to be a good wife and look after a husband, bring up children, become a good lover, grind grain and do beautiful dances. Whatever is required of a woman, the teaching is always there -- and the same applies for a young man coming into manhood.

The other thing we realized is that Africans really understand that if you live in an environment, it is very important to pay homage to that environment, to always give back when you take something. For instance, agricultural people always offer a blessing to the ancestors and ask permission before cultivation. It's a kind of respect and a feeling of trying to live in a complete world rather than in friction against your environment. So the ceremonies that keep you in balance with your environment are very strong in the traditional world.

The other balancing ceremonies are the times when people can actually be in contact with their own spirit world; at these times people pay their respects to their own belief systems and have time to think about them and reflect on their own inner thoughts.

When we come back into the Western world, we realize that many of these very cherished values are actually missing from our world. People are growing up in apartments on their own; people have areas of loneliness or areas of trauma; they are put into roles that are too complex for them, or become initiated into adulthood just by taking a driver's license. And you think to yourself, there's no real concept of letting an individual move through life from one stage to another with a sort of regular balance of learning and harmony.

We hope that "African Ceremonies" actually captivates the world and helps people realize that there are still traditional values that are very important, that the traditions in our life are very important and that the ancient values that belong to all of our cultures are very relevant.

As you tour to promote the book, are you encountering a lot of ignorance about Africa, and is that really frustrating?

Fisher: We feel that the Western world is really misled about Africa. The press and the exposure on television and radio is always the bad news -- the wars, the politics, famine, drought. Africa has had some amazingly bad and horrific situations, but behind that, it is an enormous continent, and you're really hearing only about the small pockets of disaster areas. There are hundreds and hundreds of cultures that aren't suffering from these at all, and are leading probably more prosperous, in one sense of the word, lifestyles than we are in the Western world. In Africa, the sun is always shining. And on top of that, people really enjoy laughing -- I mean, people really laugh every day. There's a sense among many cultures and different communities of how to enjoy what you have and how to balance what you're able to take on and what you're not able to take on. Sometimes a slightly simplified life is a more enjoyable life.

And when you don't have a thousand things happening at once, people get terrific enjoyment. They have great times in the markets selling butter and grain; they have wonderful times when they're herding cows. There are hard times, too, of course, but they've actually learned to really enjoy whatever is offered to them.

We feel that most Westerners have never really had a chance to be exposed to this part of Africa -- unless they've actually traveled there themselves -- so people think, "Oh, my God, you've been in such an incredibly dangerous environment," or "This must have been so difficult to do," or "Africa is going through such torment at the moment, we would never go there." But Africa is a huge continent and we can benefit so much from seeing other ways of living, from having our eyes opened. Our Western way of living is wonderful, but there are other ways that are also wonderful. There's creativity that's completely different, and there are people who have actually managed to exist in terrains that we in the Western world couldn't survive a day in. And how they've done it, and the calculation of all the things that one has to be very sensitive to -- the elements, and the rains, and the seasons, what cattle can actually take on and what they can't, and how often you have to visit a well and water animals, how long an animal can go across a desert, how long a camel can last without water. These things are very, very finely tuned by people, and it's very much a deep experience to see it.

Did you ever despair?

Fisher: I despaired once over the size of Africa. It was in covering the Sudan in doing "Africa Adorned." Sudan is by far the biggest country in Africa, and one could spend one's entire lifetime doing a book on Sudan. And when I realized that I'd taken on a project to record adornment across Africa, the despair inside of me was a confusion and an overwhelming [feeling] of "Where do I turn next?" I realized that I'd actually come to a point in southern Sudan where I couldn't figure out whether I should go north, east, south or west; the continent was just too vast. So I sat for a couple of days and then I thought, "You just have to make a stab at it." And ironically I went south across Zaire and met Carol in Niger, recording "Nomads of Niger." As it turned out, at that moment she needed a Suzuki jeep, and so the jeep that I'd been driving through Eastern Africa and southern Sudan and then across Zaire and West Africa changed hands -- and she went off in it back into Wodaabe land to record the Wodaabe people. So moments of despair, I think, have been moments only. One has had them and one has realized that in life, if you can't see an answer, you just have to sit for a little bit until it comes, and if it doesn't come, just make a stab at it. Africa's too big to think about too long; it's better just to keep going and trust that something will happen -- and something great always did.

Beckwith: I despaired when I saw the amount of need that Africans had, and how much of it was being met by world organizations that imposed what they thought was best for Africans on Africa. For example, when I was in Niger, I watched a $17 million aid program being set up for nomads, and the nomads came to us and said to us, "We've never been asked if this is going to work. But because we have a policy of hospitality and politeness toward outsiders, when they ask us if we like this project, we always say yes. We always say, 'Yes, of course in your project our cows are producing more milk,' because they need to hear the yes. They word the question in a way so that we have to say yes, but in fact, with our knowledge of the grasses and pasture, our cows are producing more milk, and we're using a system that's thousands of years old."

When I looked into this, I realized how much was being spent on this project, and how the nomadic peoples were not being asked what they needed, and how the project was setting up a dependency on the aid organization. And I felt that even though I could help the nomads in a very small way, I could make sure that any well that we raised money to help the nomads dig would belong to the nomads: "He who digs the well owns the well." He who digs the well knows how many people can come to the well before the water's depleted, and how much pasture there is around the well to support the animals. So that well was calculated to meet an exact need, as opposed to a well that costs 50 times more to serve everyone, and within a month there's no pasture left and everyone abandons the well. And since everyone is from different clans who don't get along with each other, you have to set up a police system at the well, too.

I despaired at the amount of "good" being brought into Africa that never succeeded in meeting need, and thought it's better to reach people successfully in a very small scale as a way of addressing need you see in Africa, rather than taking a monumental scale and not having it succeed. And I believe that it's most important to consult the elders, because the elders in every society are the repository of wisdom. They understand wisdom on so many levels, and one is survival. And if people go in and speak to the elders, they give such wonderful guidelines about how to help with survival, or how to leave people alone and let them get on with survival. That was my moment of despair.

You're both clearly so passionate about Africa. Is there a particular pinpoint for your passion that you can think of -- an incident, an encounter, something that was the doorway for your passion into Africa, or that embodies what you feel about Africa?

Beckwith: I think contact with people. In traveling across Africa, we encounter people who have very different belief systems, very different lifestyles, whether they're living in a rain forest, whether they're desert nomads, whether they're traditional animist people with traditional beliefs in the powers of the sacred forest and in nature or whether they're Amharic Christians who have a thousands-of-years-old belief system. What's extraordinary is that in living with people who are so different from us and each other, you come to realize that you're all sharing a common essence, that you all in the end have the same needs in life, the same challenges, the same questions, that your emotions are all shared.

Here you are with a Surma woman who's wearing only a large lip plate and a leather skirt and who lives in the forest. You think initially you could never find anything in common with her -- and then you're sitting side by side sharing the world together, sharing feelings about men, and about children, and about nature and survival and decoration, and about the ceremonies to come and what each stage of life is like. You feel incredibly bonded with people who are so different from you, and you somehow wish you could share with the world how possible it is to look at someone you might even think is your enemy in the Western world and realize how close you really are, and how much common ground there is between you. That happens in Africa when you open yourselves up and people open themselves up to you.

Shares