I recently received one of those schmaltzy greeting cards from a friend. You know the kind -- gooey prose in scripted font, offering messages of support and encouragement to those of us whose lives resemble a medieval village after an invasion by the Huns. You can actually find your location on the Personal Misery Index by tallying the number of these cards that appear in your mailbox.

There is a canned epistle of hope for virtually every episode of despair. Mostly they deal with relationships and breakups, but there are plenty of generic "I'll Always Be Your Friend Even Though Your Life Is an Incomprehensible Mess" ones to choose from. These are the kind of cards that arrive at my doorstep -- prepackaged missives designed to cover the vast landscape of life's tribulations in the vaguest language possible.

I'm not knocking these cards, mind you. In fact, I rather enjoy getting them. I've got quite a collection. There's a perverse gratification that comes from knowing that friends agree with my brooding assessment of my current circumstances. But I do have one complaint -- there is no card for my specific situation.

You see, after eight years of marriage, two children, one mortgage and a rather hapless attempt at pet ownership, my husband told me he is gay. Immediately thereafter he got a telephone-book-size listing of support groups and an entire community ready to embrace and congratulate him. I got nonspecific greeting cards promising me that the storm will soon pass and the clouds will lift.

I was sure I was alone in my ordeal. I convinced myself, selfishly perhaps, that the circumstances surrounding my marital breakup were unique. Research taught me otherwise: It happens that there are legions of reeling individuals out there, dealing with the emotional ramifications of discovering that the people with whom they planned to live happily ever after were harboring profound secrets and leading double lives.

I discovered my cohorts online. It was an eerie revelation. Their stories -- our stories -- are surprisingly similar, most often involving years of inexplicable neglect and intellectual dissembling followed by emotional chaos. We thought we were crazy, we were told over and over again by our spouses that our instincts were off the mark and then -- slam! -- we learned the truth.

These people, their stories, gave me purchase in a peculiar situation, something I couldn't find in traditional therapy. At first I simply lurked and cried out loud at the amazing parallels in our experiences. I read postings about "Gay Hubby's Excuses for No Sex" that were both agonizing and liberating. I read stories about how angry some gay spouses became when confronted with "The Question," and how helpless and withholding they could be with information and emotional support.

When I finally had the courage to post a message myself, I titled it "New to This" and briefly told my sorry tale. I was with my husband for 10 years, married for eight. He was my best friend and, for a short period of time, my lover. We had two children, a home and so much in common that most people assumed we were a perfect match.

But something was amiss. He became increasingly indifferent toward me, unaffectionate and quick to erupt in anger. My struggle with him was private and sensitive, a conflict between intimates in which one party refused to communicate honestly with the other. I had a nagging feeling, so went digging for answers myself, like an archaeologist searching for a lost city. That's when I unearthed the photographs -- homoerotic memoirs of my husband's sexual adventures prior to our marriage. I was paralyzed.

It took me a long time to mention the photographs to anyone, including my husband, because I so desperately did not want to believe what I thought they might be telling me. So I crawled into the cave of denial with him and stayed there for years.

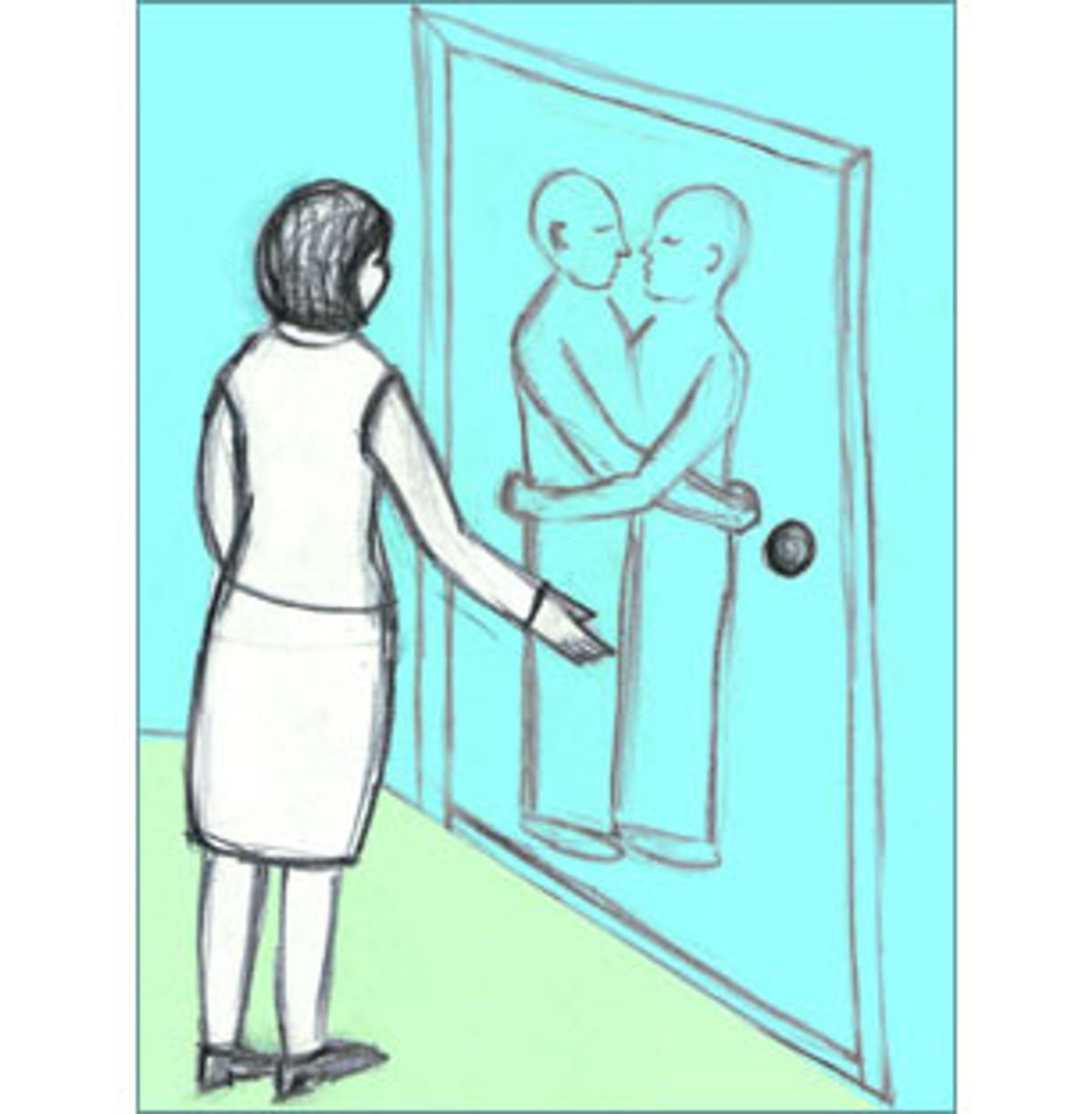

But our relationship slowly deteriorated -- he became little more than an agitated roommate subject to fits of anger toward the world, and especially toward me. I repeatedly told him of my suspicions, and he repeatedly denied them. Only when I angrily slapped the photographs down on the dining room table did he finally tell me about his homosexuality. I received no detailed explanation, no heart-to-heart exchange about his profound struggle or my role in his life over the past 10 years. Basically he just gave me the short version -- he was finally free.

I, on the other hand, felt like a captive, wrapped in a blanket of depression trying to reconcile a lifetime of lies and deceit. Why did he marry me in the first place? How blind could I have been? Who exactly was he thinking of during those infrequent times we had sex? Why did he wait so long to tell me? Did he ever love me? He was impatient with my torment and stormed out the door when my questions (and I had many) became too probing or uncomfortable for him.

Amity Pierce Buxton, author of "The Other Side of the Closet: The Coming-Out Crisis for Straight Spouses and Families," estimates that 2 million families have been affected or will be affected by the fallout from "mixed orientation marriages." Jean Copeland, a veteran member and host of the online support group Straight Spouse Network, calls Buxton's number "conservative" and adds, "We have only seen the tip of the iceberg."

As it becomes a less frightening process to come out, she explains, more gays and lesbians married to straight spouses will find the courage to reveal their feelings and more of the spouses left behind will speak up.

Copeland says she found little support after discovering that her husband of 26 years was gay, so she channeled her energy into heightening public awareness of this complex issue and providing a safe haven online for dumped spouses to seek advice, gain perspective or simply vent. The ultimate goal, she says, is "to lessen the isolation of spouses and offer them as wide a range of resources for support as we can." In the four years since Copeland came to the network, she says, she has watched it mature from a mere six members to thousands of visitors and veteran participants.

The Internet is familiar territory to a lot of the dejected and rejected spouses, though not always as a source of solace. Many of us were made aware through domestic disaster that there are hundreds of chat rooms and message boards out there where gay spouses meet or arrange meetings with new partners or engage in cybertrysts without compromising their carefully maintained facade.

While I had heard some fairly amazing tales from out-of-the-closet unmarried gay men before, the cyberworld allowed me to watch it go down. There they are, "happily married men," posting their profiles online in search of "discreet encounters" with other men. Ironically, these sites offer troubled straight spouses a means of uncovering the truth about their life companions (we do snoop) and a way to find support after the explosive revelations.

Very little has been written about the impact of the coming-out process on straight spouses and their children. Buxton's book, published in 1994, is considered the most reliable text. Writer Lisa Rogak, whose husband came out three years ago after two years of marriage, published a novel last year -- "Pretzel Logic" -- that is loosely based on her own experience. "Husbands Who Love Men" by Aileen H. Atwood also is popular in the support community for straight spouses. And Copeland is a contributor to "The Gay Husband Checklist," a resource book by Bonnie Kaye on mixed-orientation marriage scheduled to be published later this year.

Buxton, who is updating her book, says that "straight spouses go into their closets when their spouses come out. They therefore cope with painful issues in isolation and feel they are the only ones in this bizarre situation." Adds Rogak, "It drops on you like a bomb out of nowhere. At first you think that since it appeared instantly, it will go away instantly, so a lot of people suffer silently, hoping the whole mess will go away by itself."

The most common scenario, say Buxton and others, involves straight women married to gay men. Our stories differ in the particulars, but we do tend to share feelings of anger and humiliation at being used, posted as sentries to guard our husbands from the judgments of a hostile and sometimes violently homophobic world. We mourn the lost years -- in some cases, many years -- that might have been spent rebuilding our lives instead of stumbling blindly along with someone who was building a new life behind our backs, preparing to leave when the time was right.

Watching one's spouse leave the closet can be painful viewing. It can be hard to dwell -- with kindness and political correctness -- on the happiness you might feel for a loved one who is finally acting on his or her desires. Immediately after our separation my husband began dating and informed me that it "felt right." He reveled in his new life -- accessorized by a new car, a gym membership, a new circle of supportive companions and a lover.

I have become his 10-year mistake, someone who pesters him for answers he doesn't want to provide. I'm told to "move on" because he has. But his journey is new, one in which he is finally realizing his true being. My journey is more of a static exercise -- I've pulled emotional K.P. I try to fathom the deceit of a lot of years while caring for two young daughters who are confused and devastated by the breakup of their family. They know only that Daddy couldn't love Mommy the way she needed to be loved, but still refer to that empty spot on my bed as "Daddy's side."

Of course, not all of the suddenly single spouses are women. And not all of the marriages end. Some couples try to muddle through. Buxton's research indicates that while only a minority of unions last more than three years after a spouse comes out of the closet, some do endure. Most of the known marriages that last involve bisexual husbands.

Sarah and Don (not their real names) have been married for 30 years, and for the past six she has known of his same-sex yearnings. While Don professes his love for Sarah and his desire to keep the marriage intact, she experienced all the stages of grieving before agreeing to a "don't ask, don't tell" arrangement. They have a committed relationship in which there is an unspoken agreement that he will periodically have homosexual liaisons. It is not perfect, she admits, but neither she nor her husband could endure the alternative of ending the marriage.

The question that plagues us -- straight and gay -- is why we get married in the first place. Buxton, despite her years of research, has nothing to reveal except what we mostly already know: The vast majority of gay men and women who married straight partners truly loved them, wanted children and felt enormous pressure to conform to the cultural standard. Many believed that being safely ensconced in a heterosexual union would somehow quiet their same-sex longings.

But those of us who are left behind find it difficult, if not impossible, to integrate this cold logic into our disrupted lives. We are, so often, the last to know and the first to be vilified. We feel chosen and sacrificed by our spouses to resolve their inner conflicts. Our trust evaporates; our hearts are broken.

Several gay rights organizations are sponsoring a Millennium March in Washington this weekend. A contingent of straight spouses will be present to demonstrate that we do exist. It will be one of the first acts of public unity by the former and current partners of many who march. You could say that we are coming out of the closet. At last.

Shares