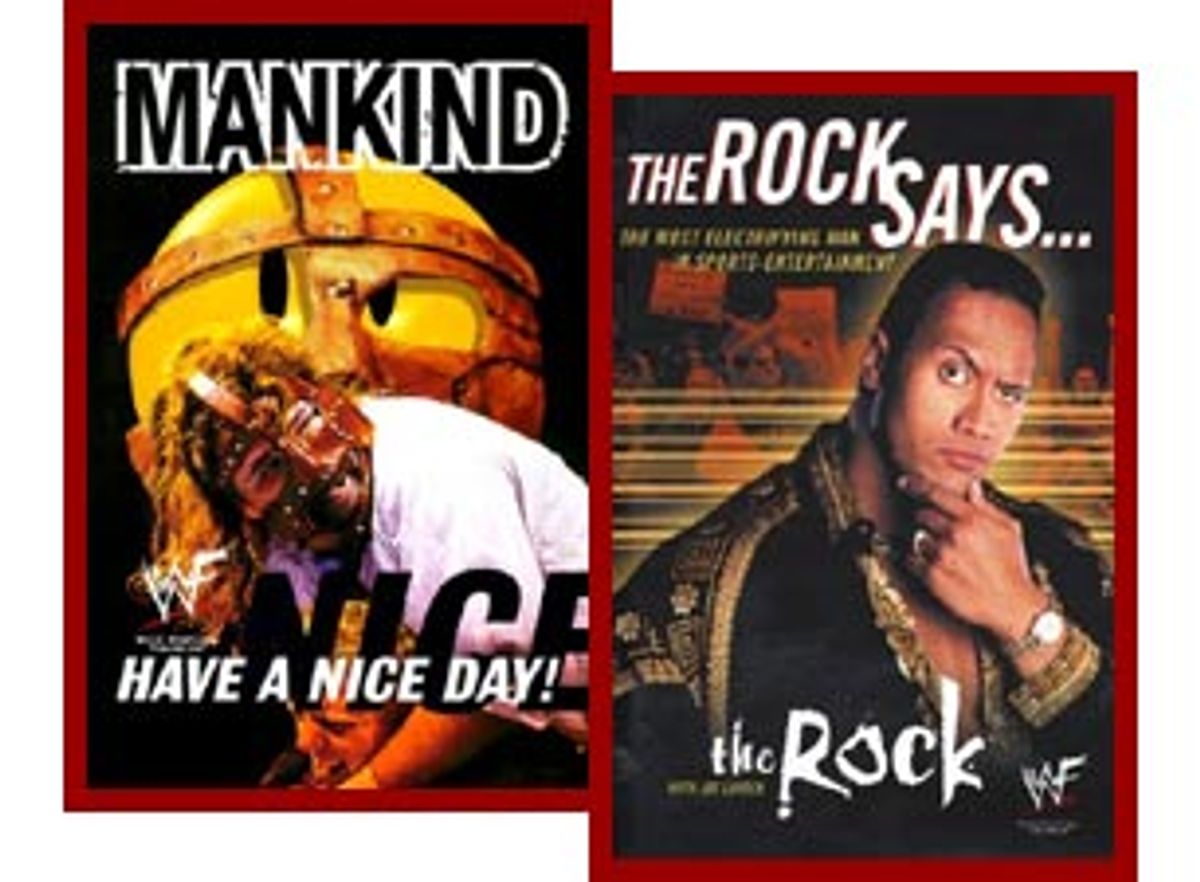

In ordinary American speech, to open up is to share your thoughts and feelings, to become emotionally vulnerable. In professional wrestling, to open up is to bleed. Mick Foley -- known to wrestling fans as the lunatic Mankind and, before that, as the wild man Cactus Jack -- has opened up, in both senses of the term, more than most people. Maybe it comes to the same thing in the end. As he suggests in his winsome bestseller, "Have a Nice Day!" his intense connection with his fans seems to correlate with his reckless abandon, his willingness to absorb punishment while they watch in some mixture of horror and delight. Almost literally, he sheds blood for their sins.

If Foley's memoir, purportedly written by him on 760 pages of loose-leaf notebook paper, demonstrates that genuine struggle and agony remain compelling even in the business of fakery, "The Rock Says ..." tells a different story. The sometime World Wrestling Federation champion known as the Rock -- earlier Rocky Maivia, before that Flex Kavana and earlier still Dwayne Johnson, his given name -- is a charismatic, strikingly handsome performer with a finely honed sense of ring shtick. But this ghostwritten autobiography is pretty much what you'd expect from the newborn genre of hardcover wrestling memoir: a milange of appreciative anecdotes about the Rock's family and friends along with boastful recountings of his bouts that could have been extracted from WWF press releases. Both books have lingered on or near the New York Times bestseller list since they were published last fall, and if that tells us something it's probably trite: Wrestling, like publishing and life itself, is full of crap and full of surprises.

What the WWF's immensely successful foray into book publishing -- in collaboration with HarperCollins celebrity editor Judith Regan -- cannot explain is why a seemingly normal human being like Foley needs to wear a leather mask and get thrown onto cement floors for a living, or why so many Americans are enthralled by that. On one level, it's a dumb question. Wrestling has become the primary Information Age vehicle for the ancient traditions of circus and popular theater, and it isn't just reverse-snob academics who think so. It's right there in the Rock's book: "We're producing a live play, a highly physical, male-oriented soap opera, and [WWF president] Vince McMahon is our director. You have to look at it and judge it in that context."

That said, it's also true that the 1990s saw a tremendous renaissance of what could be called redneck culture, as wrestling, stock-car racing and country music all exploded in popularity. You could almost say that American mass culture has split into two zones of influence, and that everything

outside the black zone is pretty much the redneck zone. While wrestling still attracts a mainly white demographic, it sure as hell crosses those racial and cultural boundaries more than Jeff Gordon or George Strait ever will. (The Rock, for example, is of Samoan and African-American ancestry.) The peculiar genius of McMahon deserves its own book, but one of its key elements has been his consistent refusal to recognize the traditional limits on the wrestling business. Branching into publishing was no more bizarre than incorporating himself and his family in the WWF's running story lines (as nefarious heels, of course) or pushing what had always been wholesome Saturday morning showboating into NC-17 lewdness and violence.

Both McMahon's WWF and his principal rival, Ted Turner's World Championship Wrestling, have long admitted that match outcomes and the backstage plotlines known as "angles" are carefully scripted. But the blood shed when the script calls for a star like Mankind or the Rock to be opened up is real enough, as is the risk of serious injury. In the most infamous "shoot," or unscripted event, of recent years, WWF performer Owen Hart died last May after an aerial stunt went awry, sending him plunging 90 feet into the ring of a Kansas City, Mo., arena.

As a "good worker" known for his ability to take a "bump" (i.e., a horrendous beating), Foley has had his ear ripped off and four teeth knocked out and has suffered eight concussions, several broken bones and countless lacerations -- without even going into the muscle tears, dislocations and burn injuries. As the world of '90s wrestling has become increasingly baroque, his characters have been strangled with barbed wire, impaled on beds of nails and scarred by explosives. He has come home so often wearing the "crimson mask" (that is, with his face covered in blood) that his wife calls his post-match cleanup ritual the "Norman Bates shower." He once drove his kids to visit their grandparents, he writes, with his scalp still full of glass shards.

As a self-interrogating memoirist, Foley may be a few chops short of Frank McCourt, but through all his tales of mayhem he remains an agreeable raconteur, always happy to spin a yarn or crack a joke at his own expense. Given his greatest area of skill as a wrestler -- which is, as he puts it, "taking an ass kicking" -- a sense of humor is probably a prerequisite. Before McMahon hired him to play the slobbering, demented Mankind character, Foley had spent years as the shaggy, lumberjackesque Cactus Jack, traveling from West Virginia to Japan to Burkina Faso and sometimes earning as little as $25 per pounding (when he got paid at all). If the catalog of names, places and injuries is likely to numb nonfans, wrestling aficionados will devour Foley's exhaustive recall of his nights working for the Continental Wrestling Association (Memphis), World Class Championship Wrestling (Dallas), the ultraviolent Extreme Championship Wrestling (Philadelphia) and any number of smaller "territories."

Foley's characters have been heels for most of his career, but in Turner's WCW Cactus Jack briefly became a "babyface" (or good guy), and Mankind was actually awarded a short stint as WWF champion. Even if readers have no real idea why Foley has inflicted this bizarre occupation on himself and his family, we can only feel grateful for these symbolic victories. After all, the bearlike man who allows himself to be thrown off 12-foot-high cages is nothing more than a big sweetie pie, not too far removed from the awkward Long Island teenager who was chronically hopeless with chicks and obsessed with TV wrestling. "I cry during the Christmas episode of 'Happy Days,'" Foley tells us, "the one where Richie spots Fonzie heating up a can of ravioli by himself on Christmas Eve." Later, remembering his fixation on female sitcom stars of the Barbara Eden-Julie Newmar ilk, he muses: "I might be able to nail some of them now that they're sixtyish and I'm on TV."

It would be a gross exaggeration to call Foley an intellectual, but he eagerly supports the notion that a good education is vital, even for those in decidedly unacademic surroundings. It was all that time he spent in German class that allowed him to utter, one night in Munich, a sentence that, as he observes, "probably had never been used before, and possibly will never be used again: 'Vergessen Sie nicht, bitte, mein ohr in der Plastik Tasche zu bringen.'" ("Please don't forget to bring my ear in the plastic bag.")

There are no foreign-language jokes in the Rock's book, no wry observations of his own inadequacies (there are none, it seems) or hard-luck stories about wrestling before two dozen abusive yokels in some freezing Appalachian gym. Perhaps that's only fitting, for the Rock is essentially WWF royalty, a golden child of the squared circle. His grandfather, "High Chief" Peter Maivia, wrestled in bare feet and traditional Samoan drag, while his father, Rocky Johnson, was among the first black wrestlers to make it big in the '60s and '70s. When Dwayne Johnson washed out as a pro football player in his early 20s -- he had played alongside several future NFL stars at the University of Miami -- he had the connections (and the athleticism) to move rapidly to star billing in the WWF.

Those who semiconsciously plow through "The Rock Says ..." will discover a few gems of valuable information on the biz, and Johnson's path toward becoming "the most electrifying man in sports entertainment" is not without interest. For some reason, this book is far more specific about how angles and bouts are developed and scripted than Foley's is. Furthermore, the Rock's journey from being a clean-cut babyface the public hated to being an arrogant heel it loved -- and finally to becoming the most abrasive and assholish of babyfaces -- offers an intriguing lesson in Machiavellian mob psychology.

But a book can capture only the letter and not the spirit of the Rock's ring persona, a strange and brilliant creation that sometimes seems like a parody of a lost original. His pseudo-aristocratic demeanor, his lexicon of invented catchphrases, his insistence on speaking in the third person, his almost fascistic invocation of "the people" -- they're all good, but frankly they're best delivered live and in modest doses. Mind you (to lapse into Rock-speak), I'm not saying the Rock is just some roody-poo standing on the corner of Know Your Role Boulevard and Jabroni Drive. Far from it.

It's just that the rhythm of "The Rock Says ..." gets pretty tiresome. On one hand, we get heartwarming family history, supportive comments about the Rock's hardworking wrestling peers and generic journal-entry thoughts. ("This is a strange and wonderful world in which we live, and it takes time to figure out how to deal with the quirks and peculiarities.") Then there are disconnected chunks of third-person narration in which the wall between performer and

audience is suddenly rebuilt, and we're regaled with accounts of how the People's Champion did layeth the smack down on this, that or the other candy-ass jabroni. The Rock's classic matches with "Stone Cold" Steve Austin were great live theater, all right, but on the page they lose, well, just about everything.

Rock, here's a memo from "the most electrifying man in book reviewing": When it comes to literature, know your damn role and shut your mouth. Or at least hire a competent ghostwriter.

Shares