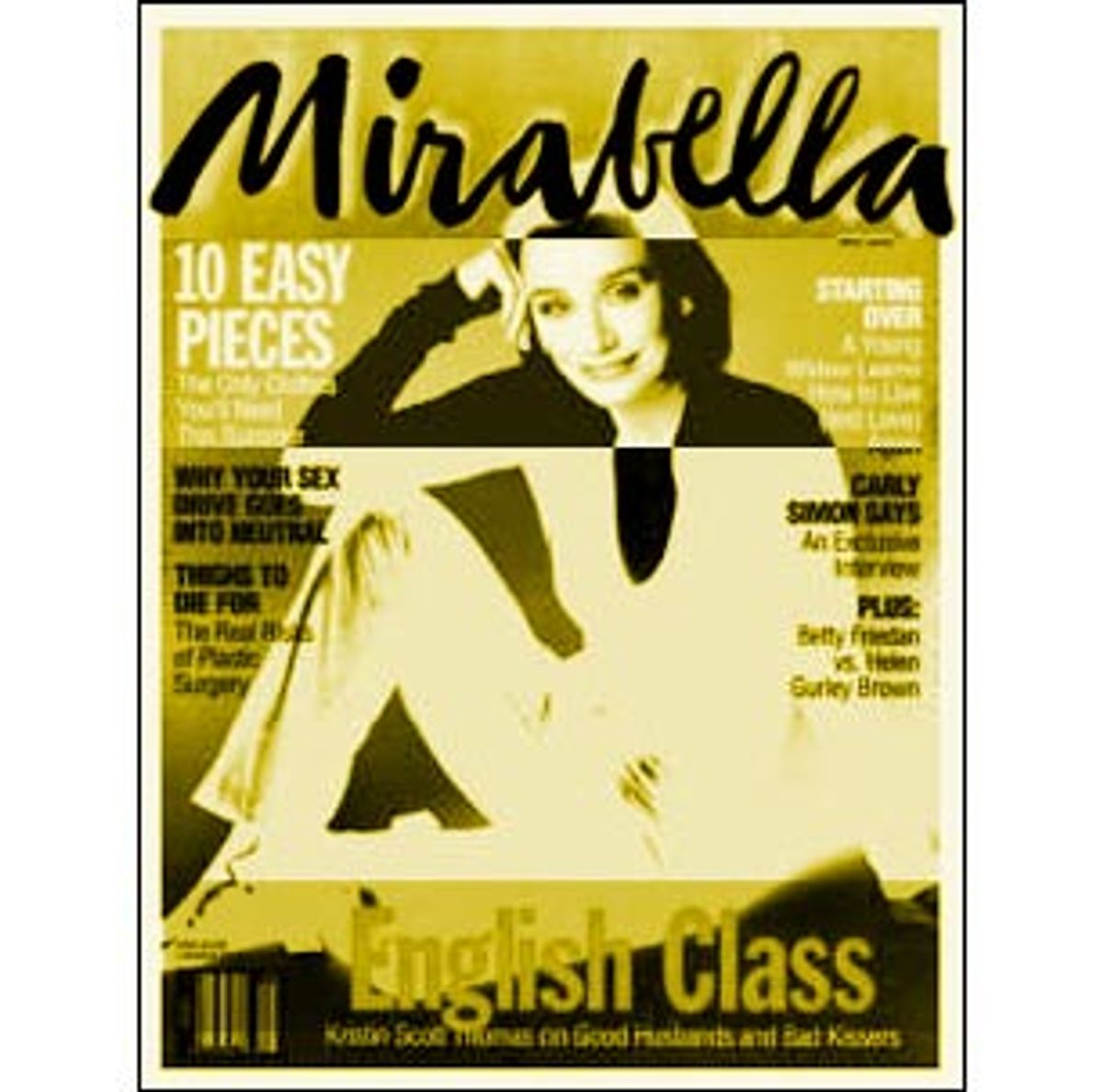

Mirabella was the most intelligent of the women's magazines, and I once wrote a book review for it. But the news of its demise makes me rejoice. It would be a good thing for everyone except those who earn their livings from the women's mags if they all disappeared.

No, this isn't another diatribe about anorexia. The women's magazines' worst sin isn't their promotion of an "unrealistic body image" or excessive thinness. (Frankly, given the ballooning of the average American, male and female, the problem is in the opposite direction.) Their sin isn't even the promotion of consumerism as a substitute for real experience, or the insipid hedonism they purvey (we'll get to that later).

The problem is that women's magazines depend on the notion that the major signifier of identity is gender, and this is less and less true. Gender roles just aren't as important in daily life anymore, and the work world is readier to ignore sex than most of us are. Mirabella's demise may be a leading indicator of this new, de-girlified reality of women's lives.

The magazine had its own internal problems -- it was bought and sold and went through several editors in its decade-and-a-half lifespan -- but the fact that its educated and affluent women readers were abandoned may herald further changes down the demographic ladder.

Then there is the psychological impact of the recent changes in our increasingly sex-neutral material world. The predominance of media that produce less tangible artifacts -- from CDs to digital cameras to VCRs to the Web -- also reduces the attention we pay to our necessarily gendered bodies. As more of our lives are conducted using digital rather than analog technologies, the role of touch diminishes, and the sensuality of life with it. This would seem to be both a good thing and a bad thing, and the consequences are still difficult to see.

Gender as the primary identifier was true for only a pretty brief period in human history, maybe 1860 to 1960. Before that, class and religion were equally basic to the way people thought about themselves; in developing countries they still are. In our Bible Belt, obviously, religion never went away as a principal component of identity. I'll bet you that Christian, Muslim or Jew have a greater resonance for many people in this country than male or female do. And while the paraphernalia of upper-class life are available to anyone with the money to buy it, those born into old money still see their class status as a fundamental aspect of their identity.

After the 1960s, age became another major way of identifying yourself, though oddly that's fading now that everyone wants to be, and to some extent thinks of herself as, young. As my 73-year-old mother says, "80, that's old."

What we're left with now is, well, interests. Narrow-casting. You're a 26-year-old female gay Chinese-American webmistress in San Francisco and you mountain-bike to work and collect vintage handbags and rock-climb on weekends. You're a 47-year-old white male lawyer in Manhattan, divorced with twin boys, and you play club tennis and serve on the board of a small theater company and collect Italian mid-century furniture.

Maybe both of these people would enjoy reading some of the same articles and you could probably sell them some of the same products, but is their gender really the key to reaching them?

The recent fate of several men's magazines -- Details, Bikini, Icon Thoughtstyle, POV have all folded -- suggests that it isn't. Young men, it seems, would rather be addressed through their particular interests -- music or extreme sports or business or pictures of naked women or literature -- than as "young men."

In fact, the American men's magazines that have targeted the "laddie" sensibility most strenuously have gone out of business the fastest, while those like GQ and Esquire that address a broader range of interests and pride themselves on the quality of their writing have flourished.

My hunch is that Mirabella's demise foreshadows the end of service-oriented women's magazines. Part of this has to do with big social trends like the rise of women in the workplace, and part of it has to do with the increased use of the Internet.

What Web browsing suggests is that narrow-casting is the best way to reach most people. Tap into the niches out of which they forge a self. Advertisers are starting to get it. But as a quick glance at the current crop of women's mags shows, they don't yet see that gender isn't the best basis for narrow-casting. For one thing, it ain't that narrow. For another, it's not related to enough economic activity. Only a small percentage of purchase decisions are directly gender-linked, mainly clothing and personal-care products. And how many of these can you buy?

I have always felt vaguely insulted by how little women's magazines deemed to sell me. Women's mags assume I never buy furniture or wine or tennis rackets or cars or in fact anything other than clothes and makeup. I guess the premise is that I will page through Tennis magazine if I am in the market for a racket and Gourmet if I want cooking equipment and Wallpaper for lamps. But the Web should have taught them, and us, that reality doesn't line up that way.

One of the corollaries of the fact that we now have everything available to us all of the time is that we are ourselves available to everyone all of the time. You can reach me reading a trade publication online and convince me to look at some sporting equipment that's on sale, or catch me on eBay trolling for art pottery and suggest a new book.

What you are less and less able to do is convince me or, especially, people under 30, to sit still for 400 pages of one thing, whether it's fashion or politics.

Then there's the issue of timeliness. When any of us can assemble a more or less ideal "magazine" from material available for free on the Web, why should we be expected to pay for a less well-selected, out-of-date version? After all, the monthly women's magazines' notion of what's new is selected, necessarily, with a three-month lead time. Even from the standpoint of beauty-product information, they are out of date compared with material easily available on the Web. Tear up that Allure, and make up your own damn magazine as you scroll.

The other problem with the gender-casting that drives women's magazines is a social ill: the reduction of gender identity to its lowest common denominator, personal appearance. This happened because somewhere along the line, some marketing genius figured out that all women wear some women's clothes and most of them wear some makeup.

All of us, male and female, are ill served by this trivialization of femininity, this equation of womanhood with the application of cosmetics and personal care.

It was not always thus. Even in the most repressive Victorian circumstances, women were granted the dignity of being esteemed for their character, and the tasks they were supposed to be good at, while no matter of choice, were not all ridiculous.

Is it more prestigious to be renowned for your bread-making or for your mascara application? For your church attendance or your knowledge of where to get a great facial? Yes, femininity is always going to be a social construct, but the version the women's mags market is a particularly mediocre one.

Moving back further in time, think about how rarely Jane Austen speaks of the appearances of her heroines, or for that matter of their clothes. Certainly these ladies lived in relatively oppressive circumstances. We would not trade places.

But they had the dignity, charm and allure of human beings whose identities were based on their character rather than their superficies. They spent their leisure hours riding or walking in the country rather than shopping for nail polish or conditioner. They danced at balls, not in classes at gyms.

Today's women's magazines are 19th century in their insistence on the indoors as woman's sphere. The world of the women's magazines is an indoor world, one of trying on clothes, of shopping for makeup and applying it. Even the exercise recommended is of the indoor variety -- aerobics, exercise classes, yoga. The emphasis in fitness is on "toning" rather than strength, on avoiding risk rather than finding pleasure in it. For every one article on some very mild adventure travel there are 10 on spas.

I know these magazines are supposed to be fun, to allow women the playfulness of experimenting with self-image and ornamentation. Of course those can be good things, in their place. But most of the women's magazines offer their readers the merest shadow of real, spine-tingling, breath-catching fun.

Most of the magazines offer a scaredy-cat hedonism of puerile pleasures like baths and massages, with a childishly erotic undercurrent. Maybe this diffuse eroticism is meant to appeal to women who want to avoid genital sexuality. And despite the celebrated emphasis of Cosmopolitan and its imitators on sex, their typical sex technique piece has all the erotic charge of an aerobics manual.

Young readers don't realize that the content is driven not by some definitive vision of what a woman is, but only by outdated visions of what women will buy. The magazines themselves have become institutions, part of our culture's definition of femininity, but we forget that their version of womanhood is but a blip in the great screen of time.

Capitalism may have created this monster, but even more capitalism is bringing it to an end. That is what is wonderful about the time we live in, and why I love capitalism: Greater efficiency and lower search costs in the exchange of information and goods do lead to greater freedom in the ways we invent ourselves.

We owe a lot of this freedom to the commercial exploitation of the Internet, and to the libertarian culture it brews. I am sympathetic to some of the observations and arguments of writers like Paulina Borsook about the shallowness of e-commerce culture. But I am overwhelmingly grateful to everyone who made it possible. Never have so many holes been dented so quickly in what looked like a monolithic culture.

At 41, I remember well what it was like to grow up in the '60s, when intelligence and interest in the sciences marked you as a weirdo in school, when half of one's questions were answered, "That's just the way it is," when women and blacks and Jews all knew their places. How good it is that we are no longer there.

I am always amazed to read that women aren't supposed to be quite comfortable online, or that we need special (third rate) Web sites of our own. Hello? The Web has given women (and people of color) a splendid new chance to defy those who would stereotype us. The only question is whether we have the courage to seize these opportunities, or whether we will continue to be the prisoners of gender -- this time in cells we build for ourselves.

Shares