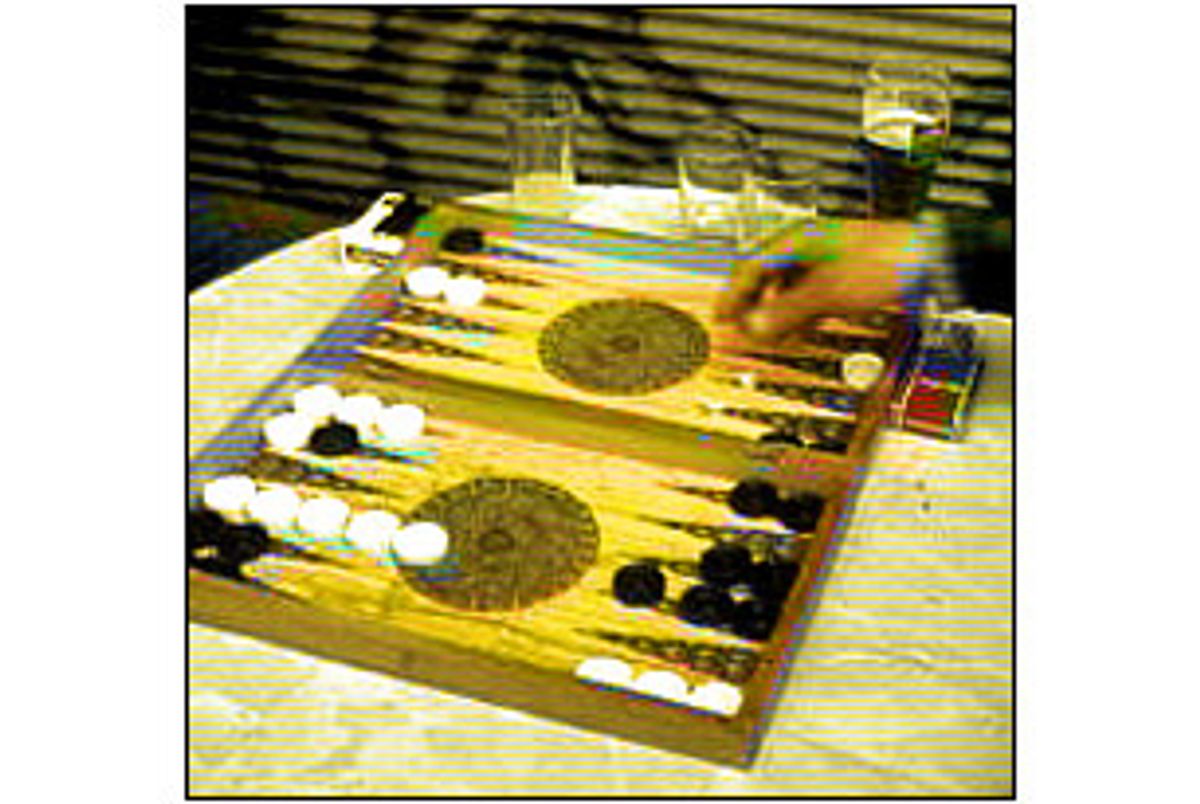

Three floors above newly sanitized Times Square, in a space that looks like the anteroom to a roller-skating rink, a shark is lazing under the track lighting waiting for the next pigeon to pay the house vig. It's a typical day here for Boris, the shark, one of about a dozen guys in Manhattan who makes his living as a backgammon gambler.

Boris, a 30ish Russian imigri living in Brooklyn, considers himself a professional in the sense that a musician is a professional; that is, he doesn't belong to any sanctioning organization, but pays rent and buys groceries with backgammon earnings, whether they be from official tournaments or from gambling.

The pros in New York hang out in small, legitimate, indoor clubs dotted around Central Park, places like the Ace Point, the Beverly Club and the New York Chess and Backgammon Club. The clubs serve as meeting points for casual players, doctors, lawyers, real estate investors, bankers and politicians as well as pros. Unlike the chump-change games played during lunch breaks from Liberty Park to Central Park, the indoor games can send losers to the money hospital.

Matt, a New York professional backgammon player with thick wild hair, is standing by the elevator bank outside the doors of one club rolling a joint. He's a former engineer in his mid-30s who generally wakes up at 2 p.m. and heads to the club. Like other pros, Matt favors casual attire. He wears shorts, a T-shirt and flip-flops to the club in the warm months and works (read: gambles) about seven months out of the year, three to five days a week.

"Backgammon is cyclical," Matt says. "If a rich guy's girlfriend takes him back or if he's got business out of town, I'm dry." When that happens, Matt, like many backgammon gamblers, turns to games such as chess and poker.

"Backgammon is like life," he explains. "It's a series of boring, innocuous days just like the day before with weddings and deaths and all that, and then there's 40 or 50 days out of the year where some really weird shit happens."

The typical daily grind means winning or losing a couple of hundred bucks in a few hours playing against a doctor or accountant in one of the local clubs. But Matt also has found himself in $100,000 games in hotel rooms stocked with money machines and call girls, matched up against high rollers from the horse-and-pony set and denizens of the underworld.

The Ace Point holds a popular tournament on the last Sunday of every month where the first-place prize is around $4,000. Not bad for a Sunday. But the real action is found in the impromptu side games. "If I don't win my match, I find a real money game," said Matt, describing how players will find a free table and make bets in another part of the club while the club-sponsored tournament rolls on.

The Ace Point, on East 60th, is bright and homey, with watercolors and a buffet table, sort of like a retirement home in Florida. The smoking section is to the left.

"We keep accounts for the players, but we have nothing to do with their winnings or losses," said one of the managers of the Ace Point. Her partner added: "Backgammon is a social game. People have to mind their p's and q's."

Sometimes players pay out of pocket, but they often use the Ace Point to transfer funds. After each game, a score sheet gets turned in at the front desk and the Ace Point cuts a check for the winner and deducts the losses from the account of the loser.

The Ace Point recently sent a tournament winner to Paris. Several pros in New York travel throughout the year to tournaments in Paris, Istanbul, Turkey, and Monte Carlo, Monaco, because the official jackpots can reach $100,000 and the side games can be just as lucrative.

One Los Angeles professional with thinning hair and a pallid complexion recently making the rounds in New York brings in about $40,000 a year, according to a competitor. "I wouldn't do this if that was all I made," said Matt. He declined to put a dollar figure on his annual take, but hinted it was in the six figures.

The winnings (at least those from the side games) are tax-free because most of the players don't pay taxes. As a result, the players asked that they not be identified by name. One player affectionately called the Croc because of his penchant for Izod shirts is now serving time in prison for tax evasion, Matt said. Other professionals include Falafel, who made his name when he was down and out and could afford to eat only falafel sandwiches; and Abe the Snake, who is reportedly a millionaire who made his money gambling in backgammon and gin rummy games.

Matt admits that his days are sometimes spent watching the closed-circuit television in one of the clubs, waiting for a good game to walk through the door. "When the buzzer rings, I go to the monitor. If I knows he's good action, I make myself available to him." By good action Matt means a moneyed player who loses.

Why bet against someone who is better? "Pigeons know they're weaker, but they love the game," Matt said the other day. Boris leaned over the backgammon board recently and offered a different excuse for the pigeons: "Sometimes people aren't satisfied losing $20. They want to lose more."

Shares