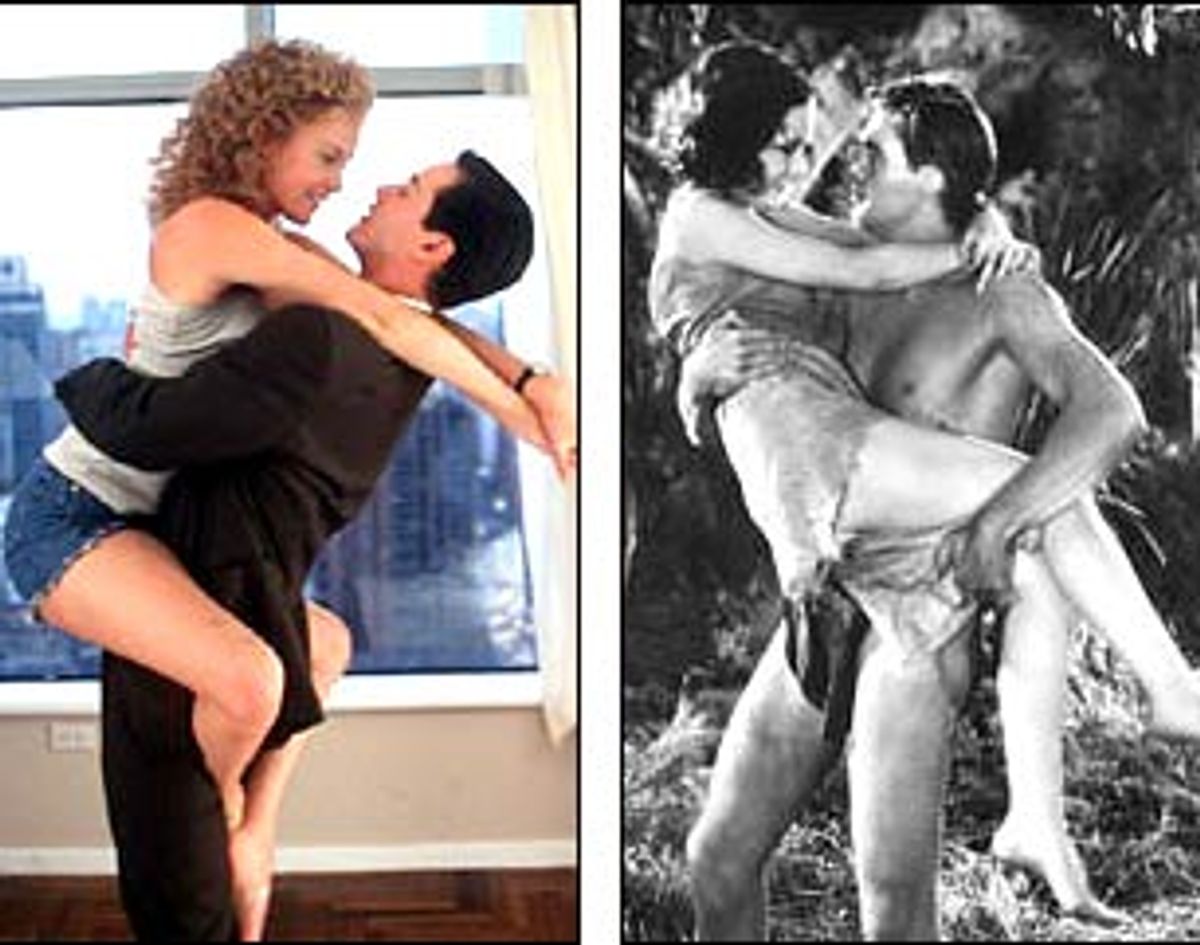

In a long, charged sequence in "Dirty Dancing," the working-class hunk Johnny (Patrick Swayze) is teaching the pampered teenager Baby (Jennifer Grey) how to dance.

At one point he's behind her and, with one hand on her bare belly, he uses the other to raise her arm up behind his head in a passionately nuzzling posture. Then he releases her arm and lets his free hand trail down her side, tracing her underarm and the outside curve of her breast. Baby bursts into laughter. And every time he attempts the move, the squirmy, eager girl gets the giggles. She just can't contain herself.

Finally, after a few stern, almost disgusted looks from Johnny, Baby manages to keep a straight face. Her eyes twinkle softly, and her movements and breathing slow down -- Baby has found her groove. Only now can the dance lesson proceed.

"Dirty Dancing" is the movie equivalent of a dopey juvenile novel, but it has a number of such primal scenes, and when it opened in 1987 it quickly became a surprise hit. Theaters were jammed with beaming, liquefying women of all ages, many of whom saw the movie over and over. What excited and pleased them wasn't just images of great pecs, fab butts and poppin' energy. It was the movie's portrayal of a young woman opening up to her deep sensations of lust and desire (and perhaps also the fantasy that she could come into her own, sexually, in a matter of weeks).

These days I think the culture of moviegoing has developed an incurable case of Baby's giggles. Too often when at the movies, I feel the way I feel when I look at the local magazine stand -- blinded by overbrightness, as though the whole world had gone on Prozac.

All this sexiness and so little eroticism. What happened? Eroticism has always been a wonderful motor force for moviegoers and moviemakers. Older readers will remember the sultriness in movies from the teens through the '80s. Silent-era stars such as Theda Bara and Clara Bow had it -- Bow's most famous movie was called "It," and erotic allure and vivacity was what "it" referred to.

Clark Gable radiated a gloating dangerousness; Cary Grant embodied, in Pauline Kael's words, "the perfect date." And Marlene Dietrich made her very first appearance in an American movie, the 1930 Josef Von Sternberg film "Morocco," dressed in a man's suit, showing off exotic cheekbones and singing a slow, insinuating song. She kissed a female customer on the mouth, tipped her hat rakishly and disappeared into the shadows, leaving audiences to look forward to what ambiguous delights she might purvey next. It was a moment of Mayan/deco splendor the equal of the ornate movie theaters of that era.

Even jungle fantasies did their best to give eroticism form. In 1932's "Tarzan, the Ape Man," Johnny Weismuller's build and swimming prowess are still impressive. In his loincloth, and with his hairless chest, this Tarzan is a genuine hunk. He has a heavy-lidded, sexily coiffed beauty, and his command of the animal kingdom has its allure.

Maureen O'Sullivan's Jane is ladylike and practical. When she's kidnapped, she's pawed, poked and hauled around by the ape man and his animal friends; her dishevelment and wet-eyed looks of distress are very suggestive. She and Tarzan grow comfortable with each other when they horse around together in a river. She's never felt so physically at ease as she does with this man-beast; for a moment, she bobs there in his arms, amused and aroused that he can't understand a word she says.

There's a dissolve, and the next time we see Jane, she's lying on a branch above a stream. Her hair is askew, her hands weave the air and water idly, and she's comfortable in her hips in a new kind of way. The image has a comic dreaminess -- it's one of the best movie images of post-coital satisfaction. Everything about Jane is smiley and relaxed; everything about her says, "So that's what it's all about."

The way black-and-white photography stylizes movie action may help explain why so many movies of the '30s have the quality of erotic reverie. But even in the 1950s, when color grew commonplace, directors and cinematographers knew how to use magazine layout-like compositions and designer-kitchen colors to stamp the eyeball in ravishing ways.

Hitchcock's 1954 "Rear Window" is full of images worthy of being isolated and turned into movie posters. Grace Kelly, with perfect blond hair and red lips, wears black and white chiffon and, later, a memorable mint-colored suit; she spends the whole movie trying to seduce James Stewart.

Skeptical at first that anything's amiss across the courtyard, she's resourceful and twinkly once her imagination is touched, and almost impossible to shock. She's like an enchanting child whose sweetness leads you to believe that she's an innocent -- yet, moments later, you stumble in on her playing sex games with a neighbor boy. The boundary between the innocent and the dirty simply doesn't exist for her. She's socially proper and privately amoral at the same time, as though that were perfectly natural; she's as open to the pleasure of illicit thoughts as the biggest lecher, and has a secret pride in that fact.

At one point she brings over to Stewart's apartment a tiny suitcase and announces that she's going to spend the weekend. When she pops the suitcase open, revealing a fluffy pile of silky and satiny nothings -- you can almost smell the gentle perfume she's sprinkled on them -- she gives Stewart a softly quizzical look. It's the slyest, most charming image of a woman (boldly and demurely, proudly yet shyly) revealing her pussy to a man that I know of.

European stars such as Jean Gabin, Jeanne Moreau and Marcello Mastroianni introduced several generations of Americans to the seductiveness of the downbeat and the fatalistic. The 1960s can also boast Anna Karina and Angie Dickinson, Federico Fellini and Claude Chabrol.

And then there's 1967 and the moment near the end of "Bonnie and Clyde" when Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway realize they're surrounded by the law; they manage to give each other a "you've been the world to me, baby" look the instant before the bullets begin to tear them apart. The 1970s were almost dementedly full of movie sex: 1971's "McCabe and Mrs. Miller's sultry, opiate-filled mood; the obvious and classic "Deep Throat" (1972) and the buttery "Last Tango in Paris" (1973) are a few examples. And in 1978, "Saturday Night Fever" showed how sexy dancing could be and how frustrated young men could get in the back seats of their cars.

Even the bad old Reagan/Bush 1980s and early 1990s yielded a generous, potent crop of erotic movies: David Lynch's "Blue Velvet," for instance, as well as Mike Figgis' "Internal Affairs," and Stephen Frears' "Dangerous Liaisons."

In the Clinton years, for whatever reasons, movie eroticism has become scarce. This is a peculiar moviegoing time. There have been a few pictures that have made a point of capturing and purveying eroticism -- Taylor Hackford's "Devil's Advocate," for example, had a reckless, overheated extravagance (and also helped introduce two promising young blonds, Charlize Theron and Connie Nielsen). The French have come through with some movies that have a shimmer: examples include "Mon Homme," "Un Coeur en Hiver" and "Romance." The straight-to-video underground still delivers the occasional treat. The Italian vampire movie "Cemetery Man," for example, is worth digging up for its trash poeticism and zanily morbid fervor.

But what's sold to us now and praised as sophisticated often couldn't be more anti-erotic. "American Beauty"? I appreciated the voyeurism and teen nudity, but could have done without the anti-suburbia scolding. "Boys Don't Cry" did deliver Chloe Sevigny bare breasted and trembling for a minute or two, but made you pay a high price -- you spend the entire movie dreading the final rape/beating/murder. "Exotica" was "Showgirls" for high-minded depressives. Neil LaBute's specialty seems to be taking the joy out of everything, in a corrosive, NC-17 kind of way.

Has there been a recent movie you've wanted to attend primarily in the hope of encountering some intriguing eroticism? Examples such as "Eyes Wide Shut" and "How Stella Got Her Groove Back" -- effective or not -- haven't been numerous.

Another puzzle of recent years is: Why have the movie critics been treating movie sex and eroticism so flippantly? Can eroticism really be of so little importance to them? What, for heaven's sake, do they go to the movies for? But perhaps they really aren't all that interested or their editors don't want them to go on about the subject. Or perhaps I'm an exception. If it weren't for movie eroticism, I might well be an average suburbanite, and an occasional moviegoer.

Because of movie eroticism, I've been a dedicated moviegoer for 30 years. I can enjoy an action/adventure pic, or an indie, or a comedy. OK, seldom an indie. (And, God knows, never a Chinese film.) But I'm always, always hoping to stumble across some resonant sexiness. I'm fascinated by the way certain shots and situations work, whether for me or for other people.

I'm amazed and tickled at how much mental energy I can spend wondering about such questions as, What happened to Debra Winger's special lustiness? And what became of the inkily perverse Jenny ("Near Dark") Wright? Ever since seeing last year's surprise Ashley Judd hit, "Double Jeopardy," I've been thinking more than anyone ought to about that movie's couple of moments of female nudity. The picture is a suspense number for McCall's subscribers, the equivalent of a Mary Higgins Clark novel. (And women generally are turned off by nudity -- as a movie executive once said to me, "Men will drive 10 miles out of their way to watch a woman take her clothes off. Women are more interested in how a man wears his clothes than in how he looks without them.")

So how did "Double Jeopardy" deliver some nudity without alienating the middle-class women in its audience? Does nudity become acceptable when the rest of the movie caters expertly to their preferences? Did they take it as a bit of enjoyable spiciness? I don't know.

I do know that heterosexual men and boys, given a camera, will within minutes start to plot ways of shooting women getting undressed. For all the propaganda encouraging us to believe that women can look at men in the same way men eye women -- of course they can, but do they in practice? -- I know of only a couple of movies where a female filmmaker looks at men with this kind of insistent gusto: Leni Riefenstahl in "Olympiad" and Kathryn Bigelow in "Point Break." My theory is that most women tend to enjoy imagining themselves as the star who reveals herself to the camera, while most men tend to enjoy imagining pointing the lens.

Is there a better way to explain why the covers of both men's magazines and women's magazines so often feature beautiful women? An underseen movie that takes some of this into account is Karen Arthur's 1987 (those '80s!) "Lady Beware," starring Diane Lane. A reworking of Hitchcock from a woman's point of view, it isn't a triumph as a thriller -- have you noticed that women generally don't show the same passion for the mechanical and the suspenseful that men often do? But it's full of unusual moments of feminine bodily self-awareneness. The beauty, vulnerability and sensuality that Arthur and Lane put onscreen is a convincing display of female power. Why haven't feminist movie critics made more of this film?

If I remain an eager moviegoer after all these years, it's largely because of my pleasure in watching female performers. I sometimes fall in love with them a little; I develop imaginary relationships with them, and wonder about their careers and their acting choices. I'm exasperated by, yet fond of, the way some actresses will protect themselves in big commercial movies, yet will give their all for art. At the moment, I'm taken by (among others) Judd. I enjoy her talent, her beauty and her several personas -- she's part down-to-earth regular gal, part I'll-do-anything starlet, part serious-artist wannabe.

In "Normal Life," Judd played a crazy working-class woman -- a frigid cock-tease -- and spent a good part of the movie naked. Has her "Double Jeopardy" audience seen "Normal Life"? Unlikely. And how would they react?

I adore Joely Richardson above all current actresses, and pray for the day when the version of "Lady Chatterley's Lover" that she filmed under Ken Russell's direction becomes available in the States. Until then, memories of her angular eccentricity, her wit and her flesh from "Drowning by Numbers" will have to do.

Patricia Arquette, another current favorite, didn't get naked onscreen until Lynch's truly awful 1997 "Lost Highway." Was it the Lynch mystique that persuaded her? In the film's one scene of loony genius, a thug holds a gun to Arquette's head as she stands before a repulsive Mafia chief. Without a word, she understands what's expected, and slowly disrobes; at first she's fearful and resentful, then she starts liking it. The scene is like a creepy embodiment of what the director-actress or audience-actress relationship, can sometimes seem to be all about, and a touching reminder of how actresses sometimes triumph over the prying eyes of the men around them, and over their own self-consciousness, too.

Arquette wore her hair blond in "Lost Highway" -- do actresses feel more comfortable doing nude scenes as blonds? Do directors prefer to put blond hair on their naked actresses? Mulling over such questions, my head spins; I'm happy.

Shares