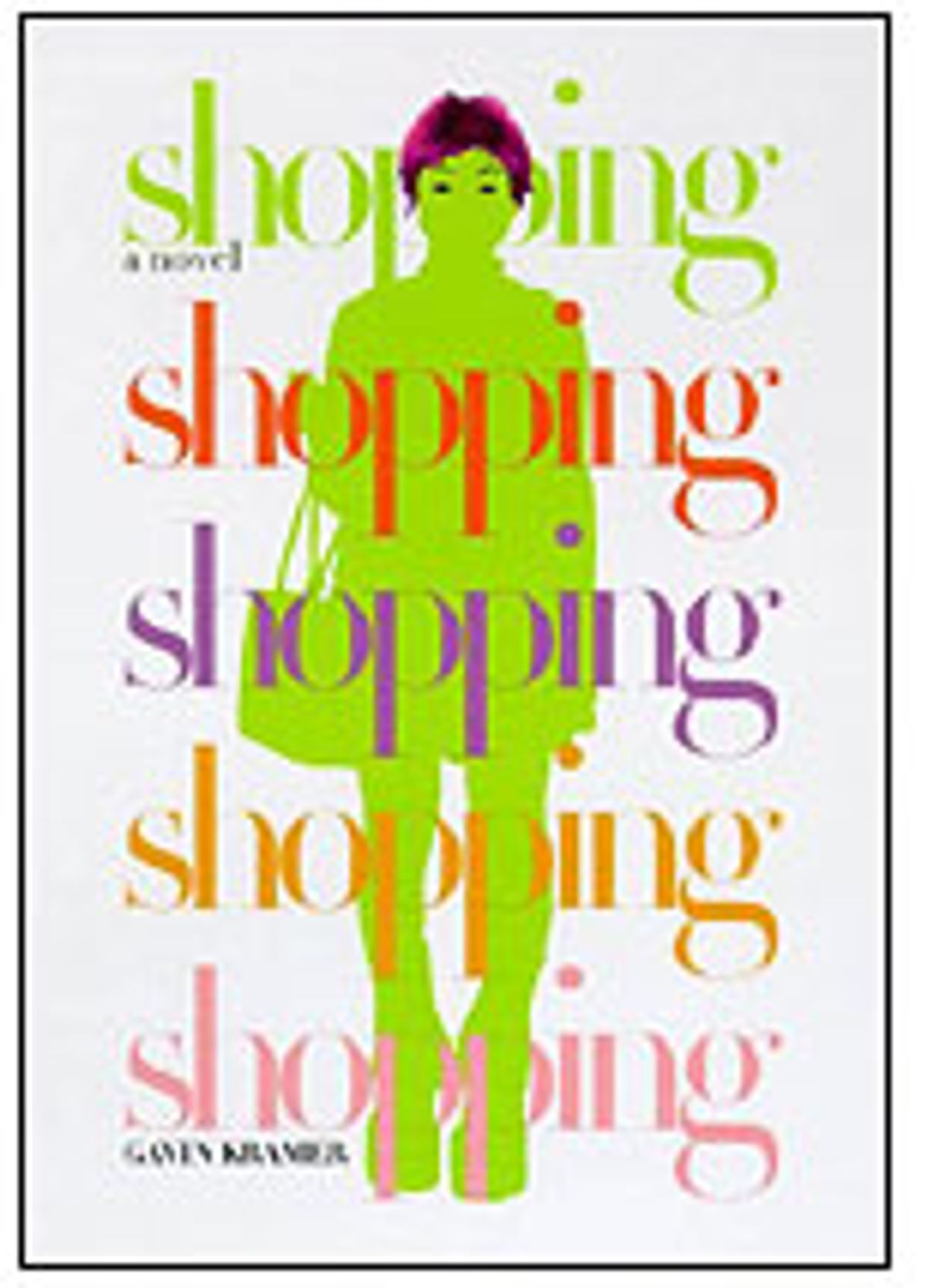

More than half a century after incinerating two of its cities and then turning the entire country into a war-spoiled quasi colony, Westerners like to think that they get Japan -- that a smooth continuum of cultural understanding bridges the Pacific, neatly joining Tokyo and its PlayStations to the Port of Los Angeles. "Shopping," Gavin Kramer's debut novel, sets out to show that we couldn't be more wrong. Short-listed for the 1998 Whitbread First Novel Prize, "Shopping" goes out of its way to depict how utterly bizarre and awkwardly, bafflingly symbiotic the relationship between Japan and its World War II foes is. As far as Kramer is concerned, the war never really ended -- it merely shifted to less violent, more ambiguous battlefields.

The plot is minimal: A jaded, expatriate narrator recounts the collapse into debauchery and near-madness of Meadowlark, an uptight, dim and lunkish fellow Englishman who finds himself slip-sliding uncontrollably across the alluring neon surfaces of Tokyo's "nightless city." "Of the young professional expatriates," the narrator says, "it was clear to which category Alistair Meadowlark belonged. They were here against their will, condemned to serve in this city because of the vast, unified effort ... to plug a once bomb-levelled country into the very heart of the worldwide money machine."

Meadowlark -- his name provides a gentle clue to his haplessness -- is a minor cog in this effort, a lawyer running on professional autopilot whose grasp of Japanese customs, mores and contemporary styles is as limited as the dicor in his bland high-rise apartment. He's an Anglo Everyman who, unfortunately, can't disappear in Tokyo because he's a big white guy in a land of small brown people. He seems to lack interest in the sexual smorgasbord of the city's Roppongi district. He has almost nothing in common with his narrating compatriot, who has gone native. (He's one of the expatriates who "liked to be seen in places where we were the sole white face.")

But then Meadowlark encounters Sachiko, a Western-fashion-obsessed teenager from Tokyo's suburbs. He meets the Asian Lolita at McDonald's, where she's sipping a strawberry milkshake. "I suspect what attracted him," the narrator says, "was the image she presented of the miniature businesswoman, the doll-size auditor of books." Later: "Each time she spoke to him ... with her girlish yet icily precise little voice, his excitement (I inferred) irrevocably grew."

It doesn't take long for Meadowlark, the British rube, to fall apart in Sachiko's tiny clutches. The process of exploring his collapse from an upstanding dullard to an unemployed, head-shaved freak dressed in a chicken suit supplies Kramer with countless opportunities to fix Japan's youthscape in his Tory moralist's gun sights. "Anything can be bought," he writes of Tokyo's insatiable consumer appetites, prefacing a list of brand-name detritus that includes inflatable geishas, green-tea-flavored condoms and the collected works of Bashv. In this context, Sachiko is less a callow 16-year-old and more a physical manifestation of how far from its insular, carefully balanced past Japan has come. She's a label whore who manipulates the "white men in suits" to fill her closets with Italian clothes.

Apart from Kramer's distinctive prose style -- which is world-weary but also extremely tense, both sinuous and spiky -- what's appealing about "Shopping" is its nearly absolute disregard for what its Japanese characters might be feeling. It's the opposite of what we expect from a novel, but it serves his purpose well. Kramer is preoccupied with the city of Tokyo, its "stratum of sadness," which "is always there: subcutaneous, beneath the skin of everything, despite the brilliance of its surface, the ceaseless movement, the apparent plenitude." But he maintains a judgmental distance from whatever emotions might exist beneath his Japanese characters' skin. He allows us mainly glimpses of how miserable the Japanese -- who lost everything in the 20th century, only to convince themselves that they had gained it back -- currently are.

In the end, Kramer endorses a nostalgic view -- a Japan of heroically antiquated wood houses straight out of Hiroshige, a Japan that has rolled the clock so far forward that if it hopes to save its soul, it must consider rolling it back. To have arrived at this verdict requires a fair amount of aesthetic and ethical courage on Kramer's part; his is an unexpectedly engaging xenophobia. In the doomed romance between Meadowlark and Sachiko, he has given us a metaphor for the strained postwar seduction of the victorious West by the vanquished East.

Shares