Man conceives brilliant idea in the heat of the night -- a Web site that will change the world as we know it. Man (and it is usually a man) throws caution to the wind and follows his dream. Man suffers, slightly, but ultimately is vindicated when adoring investors throw millions of dollars at his vision -- and our ambitious hero becomes the latest Internet poster boy.

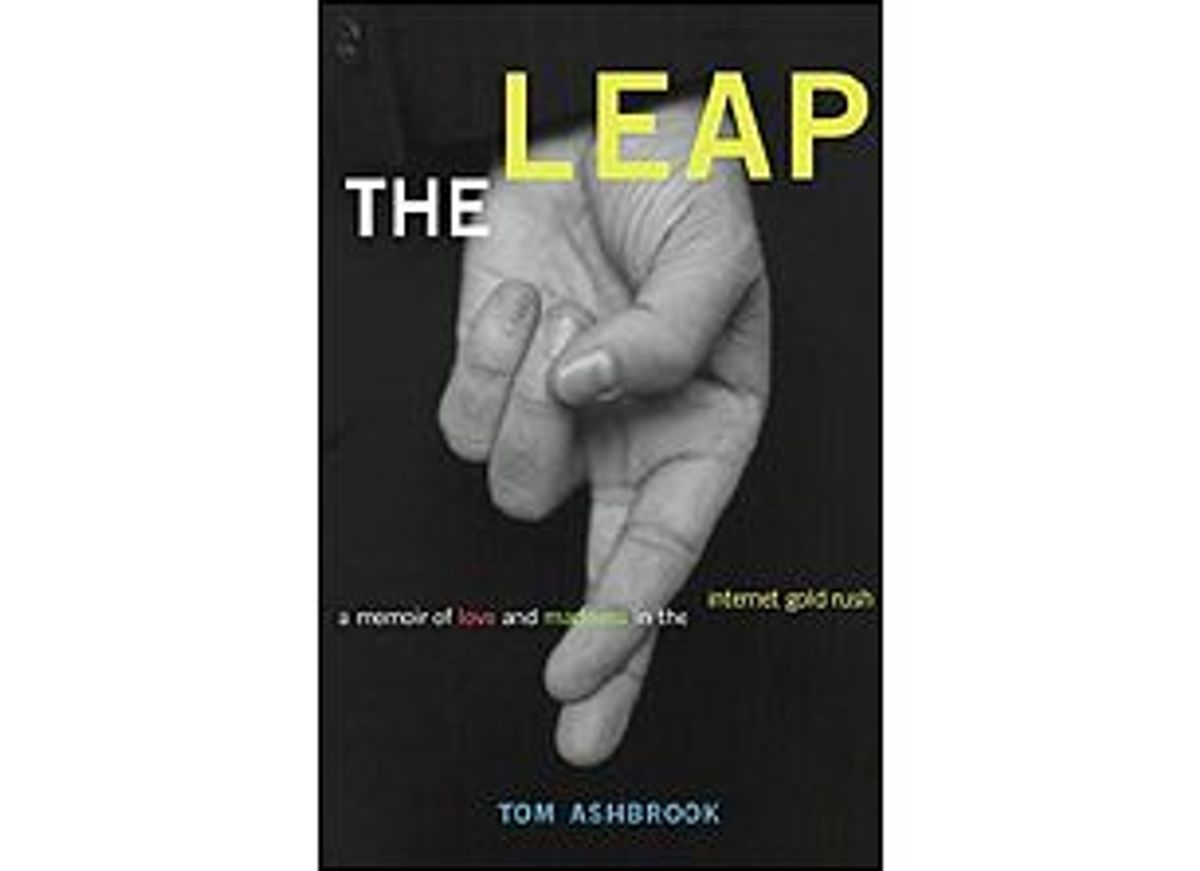

Yes, we've heard the story; we've read it hundreds of times in the five short years since the commercial Web was born. Tom Ashbrook, author of "The Leap," is determined to tell it to us again. To his credit, he still manages to make it both interesting and inspiring -- and Lord knows we can't seem to lap up enough of this thoroughly 21st century success story. I'm guessing this one will be a hit.

"The Leap" is a curiously morbid document of just how painful the Internet start-up process can be. A friendlier version of Michael Wolff's "Burn Rate" (about the starting up of a start-up), "The Leap" is laden with less juicy bridge burning and more angst, along with a happier ending. Rather than a gossipy Internet tell-all, this book is a thoughtful record of the agonies of a midlife crisis; it just happens that instead of a torrid extramarital affair or a new convertible, Ashbrook pinned his new-life hopes on the Net.

In 1995, Ashbrook was a high-powered editor and foreign correspondent for the Boston Globe; he was rapidly approaching age 40 when he began suffering a midcareer itch to get out and do something new. That new something, of course, was the Internet; his college friend Rolly Rouse, a twitchy genius type with a lot of big ideas, soon talked him into developing a business called BuildingBlocks. The vision: a CD-ROM to help homeowners conceive their "New American Dream Home" -- a product that its developers thought would inspire a renaissance of Victorian-style architecture, full of crenelation, ornate moldings and homey little details.

But it took lots of part-time days to build the "Dream Home" plan, and by then CD-ROMS were no longer hot; to revamp the business model and use 3-D modeling to create fancy home designs from scratch would have required expensive, memory-intensive technology. Besides, just as Ashbrook and Rouse started visiting venture capitalists, all the buzz was devoted to e-commerce. So they remodeled their original "Dream Home" and created an upscale shopping site -- an idea that won them $25 million in funding.

Today, you can visit BuildingBlocks' premier product at HomePortfolio.com. You can't use it to build new versions of your dream home on the fly, like some kind of Net-enabled game of Lincoln logs -- but you can pick up fancy couches and sleek chrome fixings and fireplace screens embedded with little tea lights. So much for the new Victorianism.

The grand scheme to turn modern architecture on its head was undermined by sobering market realities; as a result "The Leap" is, among other things, about the paring down of ambitious dreams.

In painstaking detail, Ashbrook describes the years of conception and frustration and poverty: dozens of rewrites of the business plan, endless meetings with venture capitalists who just didn't get it, the company bank account that kept hitting bottom and bouncing back only because of the devoted generosity of friends and neighbors. There are heart attacks and fights with his wife, meetings with advisors from Harvard Business School and late nights of agonizing soul-searching.

Too much soul-searching, in fact. It takes Ashbrook two years and approximately 200 pages to take the plunge and quit his job to commit full time to his start-up; the first two-thirds of the book is dedicated to his indecision about taking the leap, as it were. "Could this little company make it to the other side? Could we cross the canyon? Or was this just the overture to an elaborate midlife crash-and-burn? Don't think too much. Just go." Indeed, after a couple of hundred pages of this repetitive second-guessing, you want to slap him upside the head and tell him to get on with it, already!

Will Ashbrook succeed? Well, of course he will -- the kicker is given away on the book flap, which serves as a self-promotional ad for his start-up: "Tom Ashbrook ... is a founder of HomePortfolio Inc., creators of HomePortfolio.com, the leading Internet destination for premium home design products."

It's good to see that Ashbrook has learned Rule No. 1 of the business world: Never let an opportunity for free advertising slip by. The more suspicious side of me looks at this book as an extended promotion for his "vision" and the brilliance of his Web site. I can't help wondering if the site's traffic will get a boost as his book creeps up the Amazon.com online sales rankings.

If it does, he deserves it. Ashbrook is a striking writer -- sometimes pulling breathtakingly lovely prose out of his hat -- and his honesty about himself and his vision is an exhilarating change from the often wooden characterization one finds in most books chronicling the Internet age. His wife, Danielle, in particular, pops off the page -- how, you wonder, did Ashbrook manage to marry such a saint? A partner who hangs on as her husband disappears into the wilderness of Internet-mania with their life savings, sending them into precarious financial straits and forcing her to cancel her tiny daughter's dance classes?

But Ashbrook is also an unfortunately avid fan of metaphors, and goes on and on about "the tremors in the ground of our lives ... we were walking some fault line, holding hands and hoping we would keep our grip." Three hundred pages of metaphors about the Internet gold rush and new media dinosaurs and sailing off to a strange new land is simply too much. By the time the book ends with a description of how "our little boat was pushing out into the jetstream just as the lines went north," I was ready to whip out my red pen and start editing the darn thing myself, since his editor at Houghton Mifflin seems to have been far too lenient with the grandiosity extractor.

All the self-analysis, ruminations and odes to the patient wife ultimately make for a less riveting read than Wolff's viciously fascinating train wreck. "The Leap" treads dangerously close to an apology for Ashbrook's departure from the "important" world of the third estate and foreign policy to the more pedestrian pursuit of the IPO and e-commerce partnerships and "fuck you money" (as he puts it). But journalism itself, he explains, is a nasty, sinking industry fixated on O.J. Simpson and Monica Lewinsky; the Net could hardly be worse.

That's not to say that the book isn't a good read -- I'd certainly recommend it for anyone who thinks it's easy to become an Internet entrepreneur. It's refreshing to read a tale of start-up glory that details the agonies of trying to found a company when you aren't a 20- or 23-year-old wunderkind with an MBA, in-depth knowledge of C++ and no commitments except to your goldfish. As Ashbrook admitted in his farewell Op-Ed in the Boston Globe, reprinted in "The Leap" for our edification, "By 1996, the economy of the cyber era has already named its visionary explorers and brave pioneers. I make no claim at all to those ranks. Now comes the big migration, the waves of settlers. And I'm sailing to make my claim."

No pundit or futurist -- just an ordinary Joe who started an ordinary $25 million Web site. No doubt his readers will identify with him, love his story and want to try it too. If he could pull it off, why couldn't they?

Shares