Edinburgh was born of fire and sculpted by ice. At one point the entire area was under a shallow tropical sea that was subject to intense geothermal activity -- volcanoes bubbling under water. When the ice age arrived, it deposited a 2-mile-thick sheet of ice on top of this land. When the ice moved, it tipped upward so dramatically that it scraped away all the soft debris, earth and rock, and carved out seven hills. These hills became Edinburgh, and they are still volcanic.

The first references to Scotland's central city of Edinburgh appear in A.D. 160, in the notes of Ptolemy, but the area had already been inhabited for at least 6,000 years. The first residents were hunters and fishermen, followed by Celtic tribes who had been forced out of Europe. In A.D. 80, Roman legions marched in, hung out for a while and then headed home. The Romans were followed by the English, who may also be heading home.

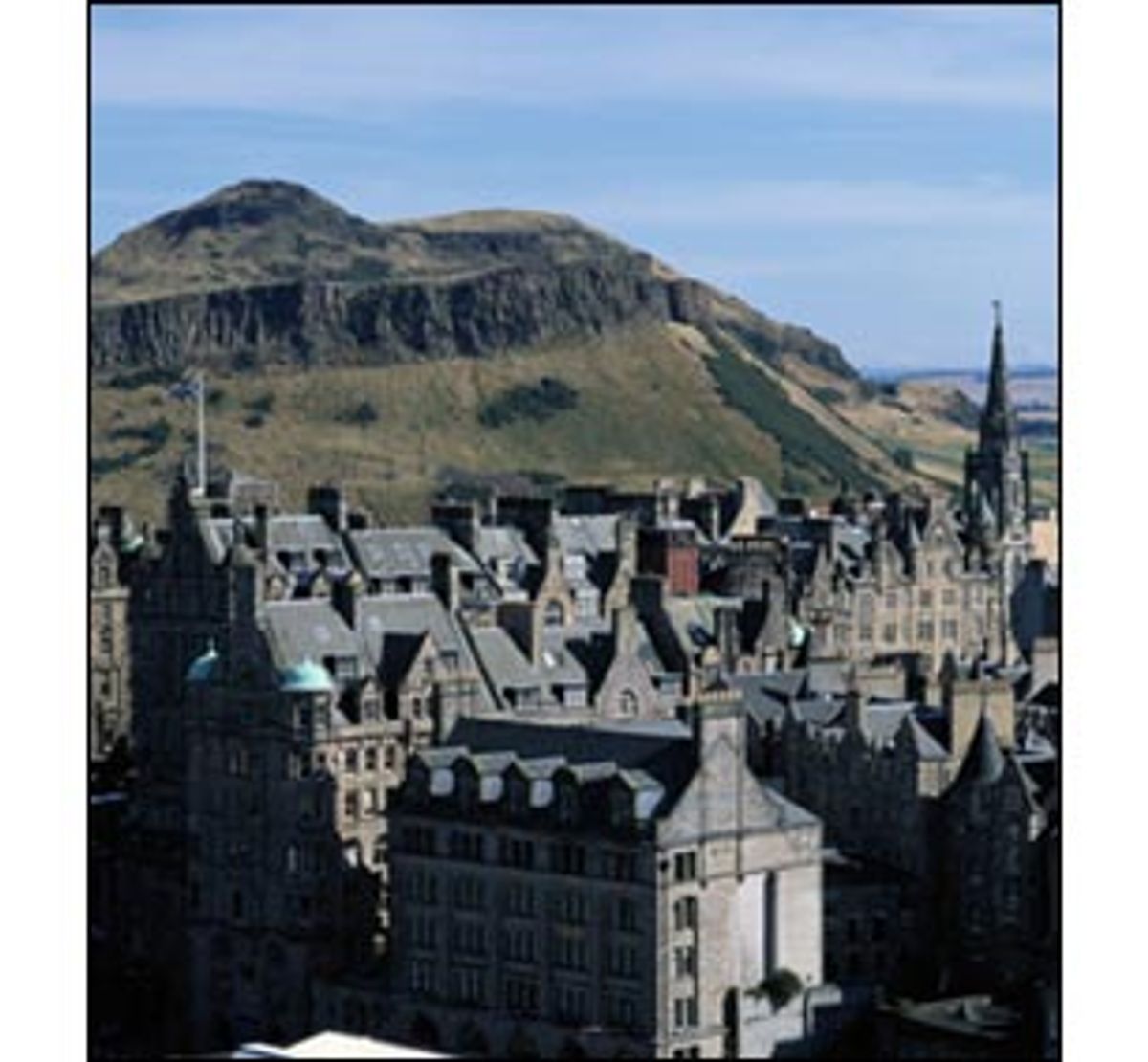

The first site in the area to be colonized was probably a hill called Arthur's Seat, just outside of modern Edinburgh. Precisely which Arthur actually sat there isn't clear. Romantics suggest the legendary King Arthur of the Round Table, though no evidence supports that view.

The top of one of Edinburgh's hills is home to the town's oldest building. It is known as "The Castle," and it dates back to the 12th century. In 1313, the Scots burned it to the ground so the English couldn't secure a stronghold in Scotland. Everything went except tiny St. Margaret's Chapel. The Scottish military still hold weddings and christenings in it, partly because of its historic significance but also because it can only hold 16 people, which makes for a very inexpensive wedding.

The youngest building on the hill went up in 1923 with rock from a chapel called St. Mary's. St. Mary's had been a Catholic chapel, demolished during the turbulence of the Reformation. But, being Scottish, they kept all the original stonework until they had something else to build. Following World War I, the stones were used to erect a memorial to the Scots who died in battle. Every Scot who died in a 20th-century conflict is listed by name. People come from all over the world to find the name of a grandfather or uncle or friend who died for Scotland.

Old Town

The castle originally served as a military fortress. People built houses in its shadow for protection, and eventually these structures formed the earliest homes in the Old Town. It became a walled city, concentrated on a rocky ridge with a huge population and no room to expand. As a result, it grew up -- with buildings as high as 16 stories. Many of these are still in use.

The Edinburgh author Robert Louis Stevenson, who wrote "Treasure Island," described what Old Town was like during the 1800s:

"It grew under the law that regulates the growth of walled cities, not out, but up. Public buildings were forced, whenever there was room for them, into the midst of thoroughfares; thoroughfares were diminished into lanes; houses sprang up, story after story, neighbor mounting upon neighbor's shoulders, until the population slept fourteen to fifteen deep, in a vertical direction."

One of the things I like about the Old Town was that all economic levels of the society lived in the same house. The rich and famous lived in the middle, and the poor and unknown lived at the top and the bottom; they were in regular contact with each other. They met in the hallways, on the staircases, in the courtyards, and they knew all about each other's lives. A dishonest businessman or an unpopular magistrate would be confronted upon arriving home. Often the confrontation took the form of a flying bucket of garbage: a most appropriate exercise of public expression. As I see our public officials leaving their elegant homes in chauffeur-driven limousines, I wonder if we should have a law requiring all government officials to go to work by public transportation -- just to keep them in touch.

Which brings me to William Brodie. During the day he was a well-respected deacon in the church, head of his guild, a magistrate and a wealthy cabinetmaker. At night, he was a burglar. As Brodie happened to be chairman of the committee examining the very crimes he committed, catching him was nearly impossible. Eventually he was caught in the act and executed on the new and improved gallows he had designed. It was the double life of William Brodie that inspired Robert Louis Stevenson to write "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde." You can visit Brodie's old stomping grounds by stopping into the Deacon Brodie pub on High Street along the Royal Mile.

The great flitting

In 1752, the Lord Mayor of Edinburgh secretly published a proposal for the improvement of the city. He complained that there was no place for the merchants of Edinburgh to do their business, no safe repository for the public records, no meeting place for the magistrates and the town council. The public agreed, and a New Town was constructed to meet the needs the lord mayor had described. Everyone with money moved from the Old Town to the New Town. The exodus from the Old Town was so fast and so dramatic that it has come to be known as "the great flitting."

The New Town of Edinburgh was built during Edinburgh's golden age, the period of amazing intellectual energy known as the Enlightenment. The New Town became the physical manifestation of what was happening in the minds of the people. In contrast to the Old Town, described by Stevenson as "so many smoky beehives," the New Town was light; a city of nature, gardens, reason. The streets were laid out symmetrically. Squares were balanced at either end, a reflection of the way the people of Edinburgh were trying to think. A good spot to see how the architecture was following the intellectual thought of the period is Charlotte Square, which looks much as it did in 1767.

A typical house from that period is the Georgian House, worth visiting at 7 Charlotte Square. It was built by Robert Adam, the greatest Edinburgh architect of the 18th century. These days it belongs to the National Trust, and has been fully restored.

Edinburgh had become an intellectual center and reminded people of ancient Greece -- to the point where it was called "the Athens of the North." But for much of the population, it was also an age of great change and confusion. For hundreds of years, the economy had been based on farming. The structure of life was simple. The year was kept by the rhythm of the seasons. And then, quite suddenly, everything began to change.

New inventions were being tested; new ideas presented. Workers were leaving the land and heading for factories. It was the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, and the great thinkers of the time were trying to explain what was happening.

One of the period's most influential thinkers was Adam Smith, who lived in Edinburgh from 1723 to 1790 and wrote "An Inquiry into the Nature and the Causes of the Wealth of Nations."

Smith tried to explain the way an industrial society worked, how it produced wealth and how it avoided chaos. He believed that everyone involved in business was interested solely in profit, and that the chaotic buying and selling of goods and services were regulated exclusively by the desire to make a buck -- or in Smith's case, a pound: "I'll supply you with something you are demanding, only if you have something that I want in exchange."

Smith also believed that any time the free market was restricted, it sent investment monies in the wrong direction. He looked at government policies that funded or protected specific elements of the economy. He looked at import duties and pointed out excessive taxation. He believed that the average businessperson would end up doing things that eventually benefited society.

On the other hand, he believed that the average government official would end up doing things that eventually hurt it. He was famous for saying, "The government that governs least is the government that governs best." Over 200 years have passed since Adam Smith's death, and these days many of his ideas are more respected than ever. Take a walk through Edinburgh, and it becomes clear that his wisdom is part of the foundation of Scottish life.

Shares