The threat of secession is dividing the deep South. A confederacy of Miami voters, incensed by the Elian Gonzalez affair, is pressing for a recall of the Cuban-American mayor, and, possibly, a partition of the city.

"If we can't live with them -- I mean with the radical Cuban element -- then let's live without them," says Annette Eisenberg, a fomenter of what has become known as the Bayshore Secession movement. According to the rebels' plan, the predominantly non-Cuban neighborhoods that hug Biscayne Bay -- including the liberal enclave of Coconut Grove and the downtown business center -- would break away from Miami and form a city known as Bayshore Miami.

On Thursday the action in the Elian saga moves to Atlanta, where lawyers for the Miami Gonzalez family on one side and Elian's father on the other will battle in federal court over the boy's right to be considered for political asylum. Whatever the court decides, the hearing will keep alive an issue that many Miami residents are ready to see resolved.

The idea of a Miami confederacy is a long shot. Attempts to divide or dissolve the city have failed in the past due to legal technicalities and the voting power of Cuban-Americans who don't want to cede relatively affluent areas of the municipality.

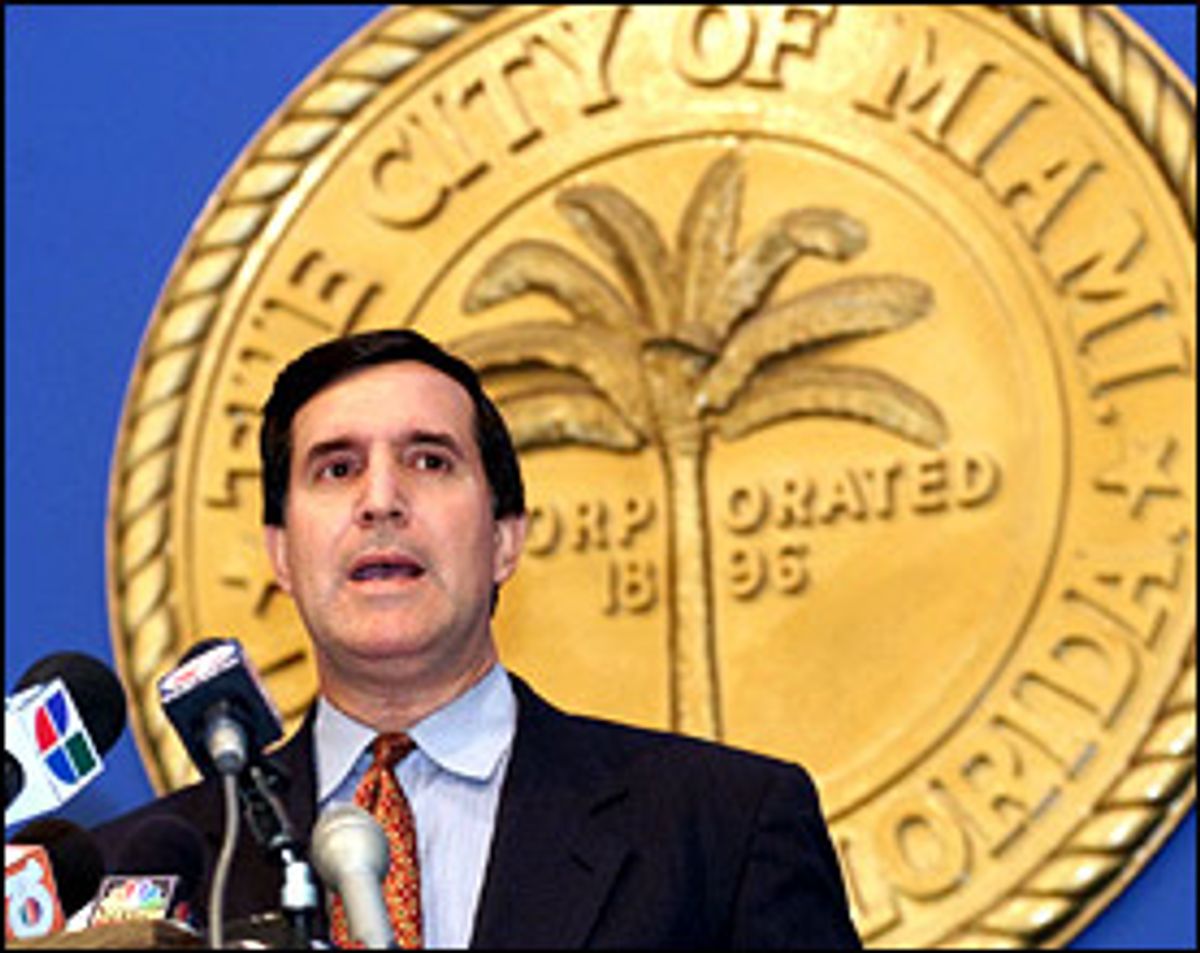

On the other hand, a movement to recall Cuban-American Mayor Joe Carollo is dead serious, its supporters say, and it may have political legs. They are organizing in the wake of a series of divisive moves by Carollo after the federal government removed Elian from the home of his Miami relatives April 22.

First, Carollo ordered the city manager, Donald Warshaw, to fire Police Chief William O'Brien after learning that O'Brien knew ahead of time about federal plans to snatch the boy, but didn't notify him. When Warshaw refused to do so, Carollo canned Warshaw. O'Brien then resigned. "I refuse to be chief of police when someone as divisive and destructive as Joe Carollo is mayor," O'Brien announced.

Those events sent City Hall and the largest city department, the police, into turmoil. But the mischief wasn't over. Warshaw briefly fought his dismissal and accused Carollo of having violated the law in the past by secretly requesting illegal surveillance of 20 people -- city commissioners, political foes and journalists, including the publisher of the Miami Herald.

Carollo denied those accusations, breaking new ground in hyperbole, in a town known for hyperbole. "These are outrageous lies," the mayor said. "Warshaw is the most evil man I have met. He makes Rasputin look like a child."

Some citizens challenged Carollo's comparison between Miami and czarist Russia. They preferred the term "banana republic," and delivered bunches of bananas to the front steps of City Hall as tribute to the mayor. But most people aren't joking. Many non-Cubans in Miami are outraged that strictly Cuban political issues have been allowed to unhinge their civic affairs and have led to the firing of experienced non-Cuban public servants.

Both the police chief and city manager were replaced by Cuban-Americans, creating an ethnic stranglehold on power in the city, and angry non-Cubans blame Carollo. Several citizens' groups have cranked up the recall campaign. The activists include George De Pontis of Coconut Grove, a chief political strategist in Carollo's past campaigns for city commissioner and mayor.

"I've always been in his corner in the past. But Miami really needs leadership right now and what is the mayor doing? He's throwing gasoline on a smoldering city," De Pontis said. "Many people who have lived here all their lives are getting the message that this is not their city. Many feel they are not being represented," De Pontis said.

The recall campaign is targeting six Miami neighborhoods, including the Carollo stronghold of Little Havana. "We feel that even there you'll find large numbers of Cuban-Americans for whom this has all been an embarrassment," he said.

This week, members of the recall movement applied for legal recognition as a political action committee from the state government in Tallahassee, the first step in any Florida recall movement. They say they will soon start circulating petitions. De Pontis said they need 6,000 verifiable signatures to achieve the first legal requirement, but they are aiming to get 6,000 in each of the six neighborhoods. With

35,000 bonafide signatures, the Carollo opponents can then demand a citywide

vote on whether the mayor should be recalled. If Carollo loses that vote, he

must stand for reelection. Neither Carollo nor his spokesperson was

available for comment on the recall Wednesday.

In relatively affluent Coconut Grove, where residents pay 15 percent of the taxes and receive only five percent of the services, the movement should be extremely strong. Organizers also expect to get major support from the city's two African-American bastions, Overtown and Liberty City.

In polls, 92 percent of South Florida blacks opposed Carollo's position on Elian, and relations between blacks and Cubans have always been rocky. "People in our part of the city are overwhelmingly in support of recalling that nut," said Nathaniel Wilcox, executive director of PULSE, a black community organization, referring to Carollo. "The only people in this city who could support him are other nuts."

The recall movement comes on the heels of a tumultuous several years in Miami city government. In 1997, a citizens group tried to pass a referendum to do away with the city government altogether, and have it come under county management. This occurred after the city was brought to the brink of bankruptcy by a $68 million budget deficit and the Cuban-American city manager, Cesar Odio, among others, was indicted for corruption. Odio ended up in prison.

But the Cuban-American voting majority defeated that effort overwhelmingly, rather than lose its political power base. In that same election, Xavier Suarez was elected mayor in a runoff against Carollo. But the courts later ruled that many of Suarez's absentee ballots were illegal -- including at least one cast by a dead man -- and Carollo was declared the winner.

Then City Commissioner Humberto Hernandez, a Suarez ally and the young darling of the exile community, was convicted of voter fraud, as were other campaign workers. Hernandez remains in prison on that and other charges involving mortgage fraud. With the backing of the courts, Carollo swept back into office, the city started recovering from its economic travails and settled down, to a degree.

Earlier this year, political foes of Carollo tried to rewrite the city charter so that he would have to face reelection this year and not next, as scheduled. A judge turned them down and trouble at City Hall subsided.

But then came Elian and the war over his custody, an issue that has divided Cubans and non-Cubans more than any other in the city's history. During the standoff, Carollo and County Mayor Alex Penelas both proclaimed that their police departments would not aid the feds in removing Elian from Miami, declarations that gained them nationwide notoriety and the outrage of non-Cuban South Floridians.

"Ever since then Penelas has been trying to pull his foot out of his mouth while Carollo has been shoving his farther in," says Coconut Grove activist Glenn Terry, another leader of the recall movement. "Some Cubans take offense when Miami is called a banana republic, but a banana republic is an entity run by irresponsible and unpredictable people. That's what we have here. This isn't anti-Cuban. In fact we need the support of those Cubans who see the need for change. Crazy Joe is getting crazier."

Carollo has been known as "Crazy Joe" for much of his checkered political career. His risumi includes work for George Wallace during the 1976 presidential campaign, a stint on the county police force and a seat on the City Commission at the tender age of 24. During that first stint on the commission he systematically made enemies at almost every level of civic life. He called the police chief "a two-bit punk. "

He also won the enmity of Cuban exile patriarch Jorge Mas Canosa, founder of the powerful Cuban American National Foundation, by revealing that a would-be business partner of Mas Canosa's in a city deal had ties to communists in Europe. Mas Canosa, who said he felt he was being red-baited, challenged Carollo to a duel. Carollo declined, but still ended up with the moniker "Crazy Joe."

"And who can argue with the fact that Joe is bananas," said Glenn Terry. Terry spoke at a small rally in Peacock Park in Coconut Grove, where the new Citizens for a Better Miami was cranking up its recall campaign. The group sold banana cake to raise funds and folks threw rotting bananas at a likeness of Carollo. Terry referred to Carollo as "a paranoid fruitcake" and made up a recall campaign anthem to the tune of "I'm a Little Teapot." It's called "I'm a Little Despot."

Recall organizers say they hope to have Carollo out of office by November. Marie Petit, who lives across town from De Pontis in Belle Mead and also worked in Carollo's past campaigns, has joined the recall movement.

"In the past it has been hard to get some people around here involved in politics," she said. "The Cuban-Americans are a majority of the voters in the city, about 60 percent, and the candidates come out of that population. Many voters just didn't want to see two Cubans beating up on each other. But I think the whole Elian think has changed the climate. People are angry. I think this recall movement is a serious one."

But not everyone believes the recall campaign can work. "The fact is, Joe is stronger than he has ever been," said Tucker Gibbs, a Coconut Grove civic leader. "People say he's crazy, but what he's done is really very smart. He has overwhelming support in the Cuban community now. Lots of people won't sign those petitions. It's a McCarthyite thing. They'll be frightened."

Jude Bagatti, who attended the Coconut Grove rally, said she wouldn't be afraid to take the petitions door to door. "I don't like people who fly American flags and then act like fascists," she said. "He's gotta go."

Shares