I am standing in the kitchen of the one they call the Pirate Kingfish. It's two weeks before the verdict will be delivered in Edwin Edwards' corruption trial, and after nagging entreaties, the former Democratic governor of Louisiana has permitted a peek into what could be his last days as a free man ("Get on down hee-ahh," he grudgingly acceded over the phone).

Edwards is late for our afternoon appointment, so I'm grilling George, his cook, a liberally tattooed ex-con. As George sings the Guv'nah's hosannas while stabbing a strawberry pie crust with a fork, a haggard Edwards walks in, tossing his keys on the counter. Back from a third day of jury deliberations, he looks unhappy to have a visitor. I don't wait for an introduction before presumptuously making chummy. I inform Edwards that George, here, has allowed me to rifle through Edwards' underwear drawers. Edwards does not offer a courtesy smile, and instead fixes me with a stare through those possum-like orbs that served him so well during governor's-mansion poker games. "It don't both-ahhh me none," he shrugs. "Everybody else does."

In Louisiana, there have always been three truisms: A) No matter how ugly a truth you visit upon a native (the state's obesity and syphilis rates are among the nation's highest, while livability and literacy rates are the lowest) they'll still give thanks to the Lord for creating Mississippi; B) If one finds oneself at a fine-dining establishment and is tempted to rely on the "How to Eat Crawfish" instruction poster, one better stick to shrimp, in the interest of avoiding ridicule; and C) If one is in the employ of the U.S. Attorney's office, one will be regarded as too sluggish, too stupid or too unlucky to catch Edwin Edwards.

Or so it seemed -- until Tuesday. That's when Edwards sat impassively in the Russell B. Long federal courthouse, where a portrait of the son of Huey Long (the original Kingfish) keeps sentry over the lobby. There, a jury convicted Edwards, the only person to ever serve four terms as governor of Louisiana, of 17 counts of racketeering, money laundering, conspiracy and extortion. It's ironic perhaps that the man often likened to a riverboat gambler (who has slipped the feds in nearly two dozen investigations, as well as two corruption trials in the 1980s) is finally headed up the river for attempting to rig the disbursement of state riverboat-casino licenses.

On the courthouse steps, Edwards looked the part of the vanquished gladiator as he stood stoically with his wife Candy, herself looking glum in an otherwise-festive pink pantsuit. Only four years ago at the building's ribbon-cutting, then-Gov. Edwards joked that the ceremony was "my first invitation to a federal courthouse not delivered by U.S. marshals." It was a typical Edwards line: no fat, black-humored, enhanced by his velveteen Cajun accent. A political Houdini, Edwards has always had a knack for making use of his worst liability (the perception that he's crooked), and wrestling it into submission in a sort of rhetorical aikido: he absorbs the momentum of the suspicion, then flips it to his advantage.

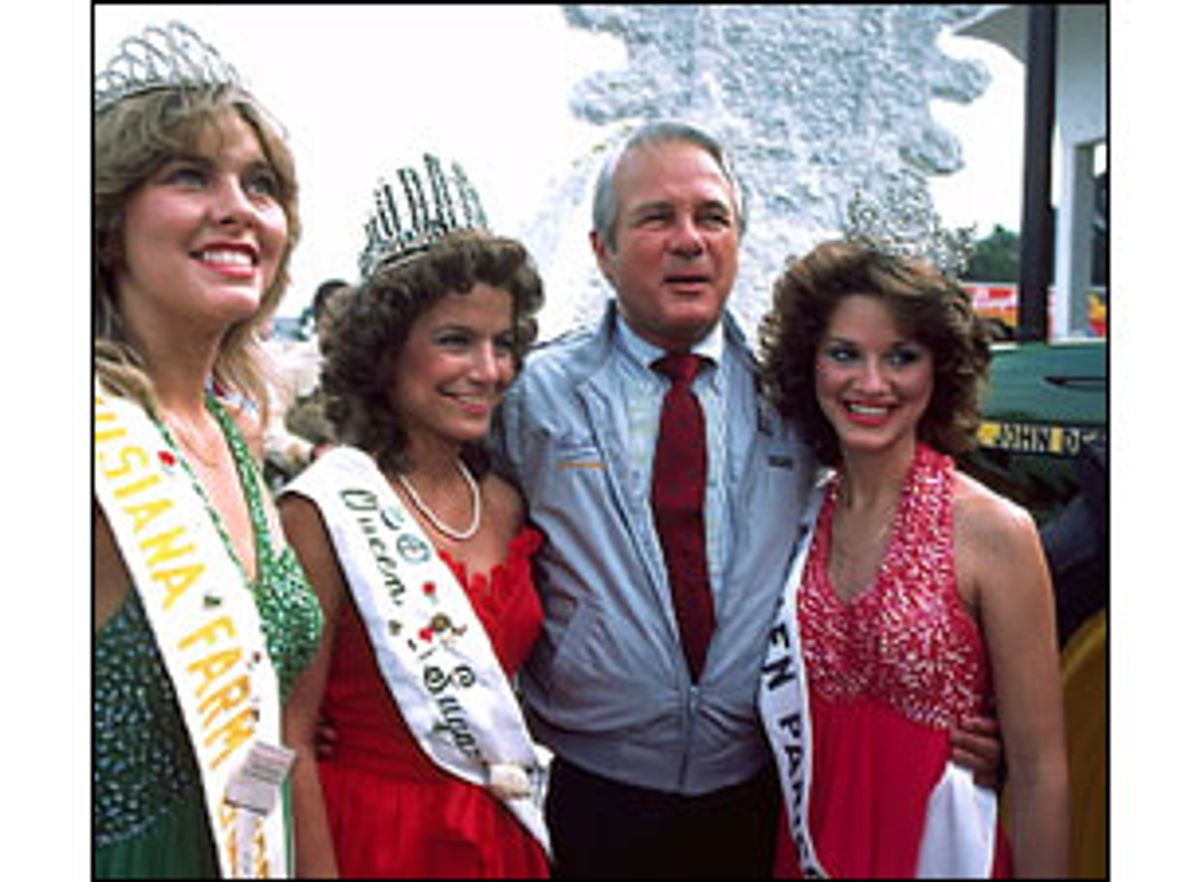

The perception has given him ample opportunity to employ his wit, which amuses even his enemies -- a large segment of his audience. In 1983, in the course of a single campaign against the vanilla incumbent Dave Treen, Edwards pulled a hat trick, formulating the three most entertaining lines ever uttered by an American politician. The deliberative Treen, he said, was so slow, "he takes an hour and a half to watch 60 Minutes." While Treen had surmised that if Edwards won, he'd be up to his armpits in the public cookie jar, Edwards rejoined that if voters reelected the ineffectual Treen, "there'll be nothing left to steal." Then, after it became apparent he would steamroll Treen, Edwards boasted that the only way he could lose was "if I get caught in bed with a dead girl or a live boy."

After the verdict, however, it was hard to tell if Edwards was joking. "I have lived 72 years of my life within the system," he said of the decision, "and I will live the rest of my life within the system." If Edwards isn't in peak comic form, it's certainly understandable. For a devoted gambler who has reaped millions rolling lucky numbers down the fast felt of Las Vegas craps tables, Edwards faced a series of daunting numbers that didn't hold much promise. A two-year FBI investigation, complete with surveillance tapes and wiretaps, yielded 26,000 recorded conversations, 5,000 of which involved Edwards. This resulted in a 33-count indictment against Edwards and six co-defendants (including his son Stephen), involving six extortion schemes in connection with 15 riverboat casino licenses.

The four-and-a-half month trial featured 66 prosecution witnesses, three of whom turned state's evidence against Edwards. Only one of those witnesses (Eddie DeBartolo Jr., former owner of the San Francisco 49ers), could directly link Edwards to an "extortion" attempt, and even then it was somewhat ambiguous, since in Louisiana, one man's graft is another's "consulting fee." DeBartolo testified that Edwards, by then out of office, scribbled a number -- $400,000 -- on a piece of paper in a Radisson hotel bar, indicating what it would take for him to wield his influence with the state Gaming Control Board to approve DeBartolo's casino license. The feds failed to record this conversation, but they were willing to take the word of DeBartolo -- which Edwards says isn't good for much. Edwards is heard on tape grousing that DeBartolo skipped out on a half-million-dollar gambling debt, a dishonorable act to a former governor who paid his casino tabs with suitcases of cash -- a habit that did not go unnoticed by investigators.

But the numbers that really mattered were those returned by the jury: two defendants acquitted, the other five guilty (including Edwards' son). Edwards himself was convicted on 17 of 26 counts, for a potential maximum sentence of 250 years. To frame that horror in Edwardsian terms: If it were possible for the 72-year-old Edwards to outlive the sentence, his 35-year-old wife Candy would no longer be less than half his age, as is commonly emphasized, but nine-tenths of it. Not that he has any intention of letting that happen. Edwards has always been a realist, and figures he only has six to 10 years left of "biblically-allotted time."

Local handicappers aren't yet making book on Edwards' chances for appeal, but if ever there was a case filled with irregularities, this was it. While most defendants are convicted by 12 angry jurors, Edwards only had 11, since Juror No. 68 (as he was known under the judge's anonymity order) was bounced in the middle of deliberations after a three-day logjam of sealed notes and closed-door huddles. The local media had a field day speculating why -- everything from the juror being a piney-woods pew-jumper, whose religious beliefs prevented him from judging others, to him being ostracized by his fellow jurors for refusing to deliberate. Whatever the reason, everyone generally agrees he was kindly predisposed toward Edwards, and one dissenting voice is all it takes to hang a jury.

Another possible reason for appeal concerns the impetuses for wiretapping Edwards in the first place. The original order came as a result of tips to the feds by Michael and Patrick Graham, two brothers who'd been investigated for everything from phony real-estate development schemes to forgery. In their new line of work as FBI informants, one of the brothers admitted that they'd been given immunity for more crimes than they could remember committing. The wiretaps were allowed to continue largely because, an FBI agent conceded in testimony, he wrongly established in affidavits that Edwards had bribed five members of the Gaming Control Board. "I cannot say Edwin Edwards passed money to anyone," said the agent. That's hardly surprising. Most veteran Edwards watchers will tell you the former governor is way too greedy to pass along a bribe.

From there, all manner of baroque absurdities abounded. Almost every transaction under investigation involved large amounts of cash hidden in strange places. There was cash carried in briefcases and worn in money vests, stashed under Jacuzzis and frozen duck carcasses, and deposited for pickup in dumpsters and ash bins. In one cash-carrying point of contention, an Edwards attorney argued that his client couldn't have worn a money belt filled with $400,000 of DeBartolo's money while walking through the San Francisco airport, since he'd have been stopped for looking "like the Michelin Man."

Edwards on tape is as clipped and cagey as ever, leaving many of the schemes open to interpretation. But some of his alleged bagmen had verbal tendencies that seemed to cast a shadow on the rectitude of their "consulting" arrangements. At one point his son Stephen can be heard wondering of a prospective business acquaintance, "You don't think that motherfucker could be wired?" And Bobby Johnson, another Edwards crony, employed similar subtlety when informing a casino applicant that he'd be requiring 12.5 percent ownership to make the deal happen: "I ain't being an iron ass, but I mean, I want a piece of that."

Johnson, a self-made cement magnate who used to live in a cardboard box under a bridge, was not the sharpest Ginsu in the knife block. His own attorney called him a "buffoon." When Johnson begged out in the middle of the trial so that he could have quintuple-bypass surgery, the crotchety Judge Frank Polozola (not-so affectionately nicknamed "Ayatollah," after threatening to jail squabbling attorneys and barking at reporters for tromping through courthouse flowerbeds) was rebuffed when he offered to let Johnson communicate with the court through an Internet hookup. Impossible, Johnson's attorney said, because Johnson could neither read nor write.

For someone as dim as Johnson, it would seem a formidable task to locate a jury of his peers. But the court managed. When deliberations began, one juror asked the judge for a dictionary to determine the meaning of extortion. Another jury note inquired, "Do you become a part of a conspiracy if you except [sic] extortion money along with others?"

But if jurors weren't easily educated, neither were they easily charmed. Edwards tried, tossing off snappy rejoinders on the stand, such as when he was asked if he'd been lying throughout his testimony. "No," he replied, "and if I were, you've got to assume I wouldn't be telling you."

Many longtime Edwards watchers, including his biographer John Maginnis, say Edwards's shtick is now shopworn. It lacks the spark and imagination of, say, his mid-'80s courtroom performances, when he was on trial (and eventually acquitted) for profiting off of state hospital contracts. Back then, Edwards rolled up to court in a horse-drawn buggy in order to illustrate the slow wheels of justice. And a younger, sprier Edwards fearlessly taunted his tormentor, U.S. Attorney John Volz, once rising to his feet for a toast in a French Quarter bar while trilling, "When my moods are over, and my time has come to pass, I hope they bury me upside down, so Volz can kiss my ass."

It's perhaps a measure of his fading potency that even his mortal enemies sound a tad nostalgic after his conviction. "It's good for the state," says Volz, who suffered a heart attack and lost two judgeships in the fallout after losing to Edwards in federal court. "Still," adds Volz, "we're seeing the end of an era. There'll never be another Edwin Edwards in our generation."

Even David Duke, who Edwards felt a certain camaraderie with, as they were "both wizards under the sheets," passes up the obvious gloat. Edwards trounced Duke in the 1991 gubernatorial election, as skeptical voters rallied behind the bumper sticker "Vote for the Crook, It's important." Duke's political career has waned ever since, but he says, "As much as I dislike Edwards, I think I dislike the wiretapping federal government a lot worse."

Times-Picayune readers seemed to agree. When, during the trial, the paper polled its readership in an Edwards referendum that ran right next to a question about banning silly string from parade routes, readers came back three-to-one in Edwards' defense. Such tolerance of Edwards is borne not only of his considerable contributions to Louisiana civic life (rewriting the Constitution, instituting open primaries, funding patronage jobs and services on the backs of once-booming oil companies), but also for his sensibility. For while every discount A.J. Liebling who parachutes into the state likes to establish that Louisiana is ruled by scampish Cajun kings, tin-pot Napoleons and back-slapping, nut-cutting populists of the Long stripe, it is a stereotype that historically has been, well, sort of true.

Novelist Walker Percy, a native, best explained the effects of cross-cultural corruption in the port city of New Orleans: "Unfortunately and all too often, the Latins learned Anglo-Saxon racial morality and the Americans learned Latin political morality. The fruit of such a mismatch is something to behold: Baptist governors and state legislators who loot the state with Catholic gaiety and Protestant industry." Edwards, unlike Huey and Earl Long, was never a Baptist (he's a non-denominational churchgoer, by way of Catholicism, by way of the Nazarenes, which is to say, he's covered his bases).

It's no small wonder why most pre-verdict discussions of Edwards' guilt or innocence, outside the courtroom, were purely academic. Much more important than "Did he do it?" was "Would he get caught?" As one of his trial-lawyer boosters snorted when I inquired what he thought of Edwards' guilt, "Hell yeah, he's a crook, but what's that got to do with anything?"

The electorate's collective yawn over such matters has historically meant a teeter-totter between Long-style populists and their less entertaining reformer counterparts. But even the latter camp, in Louisiana, can sometimes use peculiar methods. Liebling once related how Cousin Horace, his pseudonymous source, was so overcome with disgust for Long's corruption that in a flare-up of civic consciousness, he joined like-minded reformers to raise funds to bribe the Legislature to impeach him. Louisiana is probably one of the few places in the country where Potch Didier, a sheriff from Edward's native Avoyelles Parish, could win reelection while serving a sentence in his own jail. Likewise, the last three insurance commissioners have been indicted, including Jim Brown, the current one, who, as luck would have it, is a co-defendant with Edwards in an upcoming state insurance corruption trial -- yet another jurisprudence nightmare on Edwards' horizon.

Everywhere one turns, it seems, a whiff of larceny permeates. You sense it in the 34-story state capitol building in Baton Rouge, where Long fell either to an assassin's bullet, or to his bodyguards' return fire -- or, if the woman standing next to me fingering the bullet holes in the wall is to be believed, by agents of Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was concerned the Kingfish would take over the world like he had Louisiana. Throughout the edifice, inmates from the Dixon Correctional Institute swab the floors, while future inmates populate the legislative chambers (48 public officials were indicted in 1998 alone).

You also sense it pushing to the outskirts of the city, to Edwards' home in a gated golf-course community that also boasts as residents Master P, C-Murder and other felonious rappers from the No Limit empire, with whom Edwards has not yet had occasion to barbecue. Inside the tastefully decorated house, George the cook, a former governor's mansion trusty whom Edwards pardoned for his role in a robbery, holds down the kitchen.

George is whipping up strawberry and lemon icebox pies for that evening's "defendant's sup-pahhh," a regular ritual the accused and their attorneys engage in while waiting for the verdict. Andrew Martin, one of Edwards' co-defendants, who like Edwards will shortly be convicted on multiple counts of racketeering, is also mulling about the kitchen, assuring me that though I'm not invited to stay, all I'll be missing is crab rtti, shrimp as thick as midget's forearms, and people "getting drunk, singing and telling dirty jokes -- the usual routine."

As Edwards and I retreat to his living room and sink into his chenille sofa, my eyes pass over the built-in shelves which hold beautiful, leather-bound books, the spines of which appear to have never been cracked. There's "A Stillness At Appomattox," "Catch-22" and "All the King's Men" -- the story of a gifted populist Southern governor who gains the love of the people, but who suffers a fall when reverting to bribery and intimidation in the service of his selfish ambitions.

Edwards takes a while to warm up, since Judge Ayatollah has everybody spooked with his restrictive gag order prohibiting the trial's players from talking to the media. "You have to understand," Edwards says, "I can't say a damn thing." But after assuring Edwards that I won't publish until after the verdict, he relaxes, as he's never been too great a stickler for other people's rules. Of the wiretaps, which ultimately did him in, Edwards tries to take lemons and make lemon icebox pie. "Fortunately," he says, "there was nothing derogatory towards anybody -- no use of racial slurs, or threats of violence, or references to drug trafficking or anything like that."

Regarding the betrayals of old friends who flipped for the state, Edwards tries to remain a forgiving Christian, though he suggests their motivation to testify was dictated by something other than veracity. "There's no telling how much money [the feds] could have gotten out of [Eddie DiBartolo]." Edwards says. "He's worth 400 to 500 million dollars, but only had to pay a fine which is the equivalent of you paying $25. They gave him probation and no jail time, so what the hell? I'm not prepared to say I wouldn't do it myself if I was in that situation."

When discussing other incidentals that don't bode particularly well for him, he employs the Socratic method. Of the allegations that he made plans to profiteer while still governor, with payments deferred until he got out of office, he is incredulous: "You think if I was the kind of person who wanted to take a bribe, I'd do it on the installment basis?" Maintaining that he was being paid consulting fees from casino applicants, Edwards notes that in some cases, he was actually paid more money than he allegedly extorted. "If a person kidnaps your child and sends a note for a $2 million ransom," he says, "do you send him $2.2 million?"

Of payoffs being left in dumpsters, Edwards bristles with contempt. "Nobody's gonna put $100,000 in a paper bag in an ash dumpster and not wait around to see who picks it up. Do you believe that?"

I ask Edwards if the stress of the trial has caused him to lose any sleep. "Hell no," he says. "I sleep like a baby." Though he wouldn't make a prediction as to the outcome of his case ("I don't want to look like some stupid ass") he had not made much preparation to go to prison: "Not financially, not psychologically, not nothing."

We talk a bit of politics, specifically about some of the good-government reformers on the ascent of late. "[They] are all passing fancies," Edwards dismisses. "They sound good. They look good in the press. But they accomplish nothing." Edwards realizes the media no longer rewards politicians for flamboyance and eccentric individualism. He indicates that the new climate would suffocate Huey Long or Uncle Earl or maybe even a young Edwin Edwards. "I'll draw the last breath of a dying breed of populist governor," he sighs.

As for the charge that Edwards spent most of his time on the stand committing perjury, he says doing so to escape prison wouldn't be worth "condemning my soul to some never-ending hell of pain and agony and torture for lying under oath." When I suggest Edwards should become a Baptist, like the Longs, whose beliefs would not dictate that one is banished from the Kingdom for fibbing in a courtroom, Edwards scoffs. "If you're one of those once-in-grace-always-in-grace Baptists, maybe you could get away with it," he says. "But I don't know if I could ever get to the grace, so that wouldn't do me any good."

If there is one thing that Edwards the gladiator and gambler does not seem to cotton to, it's all these weak sisters taking pity on him. "Everybody was surrounding me patting me on the shoulder saying 'I'm sorry you have to go through all this,'" he says of his days on the stand. "Hell, I'm having fun. The adrenaline flows. It's the clash of minds -- the challenge. Why did Hillary climb Mt. Everest -- because it's there. I'd rather spend my time doing something else, but if I've got to spend my time doing this, let's have at it."

While I'm expected to leave before the "defendant's sup-pahh," I catch up with Edwards in court the next day. When we reconvene in the courthouse cafeteria, we're joined by his adult spitfire daughters, Victoria and Anna. Anna playfully shakes me down, telling me if I intend to interview her father, I ought to pay for breakfast. Edwards doesn't seem concerned. He's too busy working the room full of reporters, who eagerly serve as punch-line fodder when he inquires how they got through security or whether they intend to find respectable employment.

As he sits down at a Formica table, forking a Styrofoam plateful of bacon, eggs and grits, Edwards grows paranoid. The cafeteria is crawling with prosecutors and he's at least trying to observe the spirit of the Ayatollah's gag order, if not the letter. "I can't be seen talking to you while you're writing," he says, prompting me to drop my notebook under the table.

To be safe, we take it outside, and as we walk down the courthouse steps, Edwards looks at longingly at the microphoned media corral. He's been forbidden by the Ayatollah to play to the cameras, where he's always done his best work. If it wasn't for the gag order, he says, "I'd be having a press conference every day." Though Edwards hasn't been of much use to the media lately, one reporter takes a shot anyway. "Governor," he yells, "how have you been spending your time?"

"Miserably," says Edwards, pointing to me. "Look who I'm spending it with."

We adjourn to the parking lot, along with Edwards' daughters. The four of us chat in Victoria's Dodge Durango, well out of earshot of nettlesome prosecutors. "Daddy, why don't we take a ride?" Victoria offers. As we briefly tool around downtown, Victoria points nonchalantly: "That's where I used to live."

There's a fence around the grounds now, though there wasn't when Edwards was governor. He and his daughters say that during his tenure, the house was filled with an endless stream of legislators and supplicants, who had all-access passes to the governor. Sometimes they'd be lined up in the anterooms, sipping iced tea while waiting. One might even run into uninvited voters, who'd sometimes knock on the mansion door and be invited to stay for lunch. But it's different now -- with the fence and Edwards' successor, Mike Foster, a millionaire sugar heir and self-proclaimed reformer, whose campaign ads touted that he wasn't just another pretty face. "He sure isn't," quips Victoria.

Before I leave Baton Rouge, there is one more mission to carry out with Edwin Edwards. It involves the Caesar matter. If there was any doubt that the fates have decided to kick in Fast Eddie's slats, Caesar is barely living proof. It seems that on the last day of closing arguments, George the cook brought the Edwards' 7-year-old yellow Lab, Caesar, down to their lawyers' quarters to eat lunch with Edwin and Candy. But on the walk back to the courthouse, a vehicle plowed into the dog, then fled the scene (nobody knows who was driving, but some have suggested overzealous prosecutors). The car launched poor Caesar airborne, and when he hit the ground, he suffered everything from a scleral hemorrhage in his eye to a broken hip.

For a week, Caesar has been laid up at the LSU veterinary medical clinic, and now we're off to bring him home. But Edwin informs me at his house that we'll be taking separate vehicles, as he must run an undisclosed errand. To make the most use of my interview time, I suggest Candy ride with me. Edwin consents, but looks pained, as one suspects many younger men would like to part her from his company. If Candy were a refreshing beverage, she'd be sweet tea. She's all blond drawl and tanned legs, and today she is sporting linen shorts and an aquamarine shirt knotted over her taut midriff.

As Candy takes the wheel of my rental car so I can take notes, our heads pop like dashboard ornaments while she acclimates herself to my brakes. Edwin has warned her not to talk about the trial on account of the Ayatollah. So she doesn't. Instead, she talks about his prostate gland. It seems Edwin's errand involves going to give blood for a PSA test. "He doesn't have prostate cancer or anything," assures Candy. But, she says, searching for the correct medical terminology, "It's large. Most older men have enlarged prostates."

The Edwardses have been married for six years (they met when Candy was 25). And during that time, she has endured all manner of obloquy concerning her husband -- from the unsubstantiated charges that he removed expensive furnishings from the governor's mansion, to tales of his unrepentant womanizing (he reportedly used to cruise LSU's sorority row in the governor's limo). But that, Candy says, was all "B.C." their shorthand for Before Candy. "Since the day I've met him," she says, "he's been wonderful."

While Candy is not one to dwell on the specter of Edwin going to prison (she had a jitterbug band all picked out for the post-verdict victory party) she does say that Edwin told her that if he was incarcerated, "'You're going to need to go on with your life,'" she says, recoiling. "Like go on and find somebody else! As soon as he tells me that, I'm crushed. I just immediately break down."

When we arrive at the veterinary clinic, Caesar is in bad shape -- a shaved, stitched heap of surgical screws and hip plates. He looks fairly despondent. Then he sees Candy. She immediately sets about rubbing his rose-petal ears, showering him in baby talk (You're my baby, How's my baby? etc.), which he seems to enjoy -- and who wouldn't?

A while later, Edwin walks through the door and Candy's sugary drawl goes up an octave when she peppers Caesar with, "Wanna see poppy?" The dog's brush-thumping tail indicates that he does. But when Edwin approaches the cage, he is all manly vinegar.

"Git up," he barks, half mockingly.

"Look," Candy says to Edwin displaying the purple LSU kerchief around Caesar's neck, "a keepsake."

"I'll have a keepsake," Edwards cracks dryly, "a cancelled check."

For Caesar to walk out to the car, a nurse has to hammock a towel around his groin area while pulling up on both ends, providing support. As we hobble through the waiting room, an old woman tending her cat, cries out to Edwards, "Give 'em hell, Guv'nah."

Once outside, Caesar slowly limps over to a patch of grass and sniffs the ground in anticipation of his ablution, though his schwantz is aimed a bit too easterly from the pressure of the towel against it. While Edwards conspires with Candy about how to get Caesar into the vehicle, an onlooker approaches Edwards and offers her support. "I admire you," she says. "I'm one of your fans. You're going to beat the whole damn bunch of them."

Edwards neither smiles, nor does he hold his characteristic poker face. Instead, he wheels around, eyes afire, and thunders to his amen corner, "Let me tell you what, in America, nobody should be subjected to what I've been subjected to unless you're suspected of mur-dahh or espionage."

"People are out to get you," the woman concurs.

"They've been after it for a long time," Edwards says, permitting a slight grin.

As the woman departs, Edwards falls into preoccupied silence. He might be thinking about the well-being of his young wife, or the realities of imprisonment, or his prostate slowly growing to the size of a tangelo. Or maybe he's not thinking at all, as he watches Caesar, a creaky old yellow dog, trying to gain his balance in the weeds without squirting down his leg.

Shares