Los Angeles, give me some of you! Los Angeles come to me the way I came to you, my feet over your streets, you pretty town I loved you so much, you sad flower in the sand, you pretty town.

--"Ask the Dust," 1939

In the company of writers, when the conversation turns to the serendipity of literary fame -- great writers unpublished; lousy ones celebrated -- sooner or later the name John Fante will come up. Not everyone will know of him -- not on the East Coast, anyway -- but those who do will respond with feeling. To them, he'll be one of the precious proofs of literary justice: a moral story illustrating all the ills of Hollywood and the immortality of talent; a rare and precious illustration that talent, no matter what the odds, will out.

As always with these stories of virtue rewarded, it's a three-act morality play. In Fante's case, it starts in 1930 when an impoverished young Italian-American man escapes his suffocating home in Colorado, armed only with a Jesuit high school education and the insane desire to write novels, and challenges Depression-era Los Angeles to deny him his glory. Flash forward to 1978, and Act 2: The aged hero sits in a wheelchair in his luxurious Malibu, Calif., house, having lost limb and eyesight to diabetes. Between the two scenes lies a lifetime of forgotten novels, buried by a career of soul-destroying screenwriting and a half-century of dedicated drinking and gambling, a brilliant talent wasted and forgotten. And then comes the last act.

In a throwaway line in his 1978 novel, "Women," the iconic Charles Bukowski -- the best-selling cult poet whose wild readings are the stuff of beat legends and whose epic drinking, fucking and writing were captured by Mickey Rourke in the movie "Barfly" -- mentions two utterly forgotten Fante novels, published respectively in 1939 and 1938: "Ask the Dust," and "Wait Until Spring, Bandini." These novels, it turns out, had sustained Bukowski 25 years before when, in the depths of his half-mad drinking days, he found them in the Los Angeles public library.

The mention sparks interest, notably that of Bukowski's publisher, America's foremost champion of the literary avant-garde, John Martin at Black Sparrow Press -- it was Martin who had discovered Bukowski in the '60s and turned him into one of America's bestselling poets. Martin acquires a copy of "Ask the Dust" and immediately sets about putting it back into print. And over the next 10 years, not only is Fante's forgotten life's work brought back to readers, but previously rejected works are published, new ones are written and hundreds of thousands of copies are sold to a cult audience in America and a mainstream one in Europe. It is a story everyone likes to hear.

Certainly it was a story that I couldn't resist. When, in 1991, I discovered Fante, I read his life's work one book right after the other. Here, I saw, was a writer as powerful as any in the American canon and far more subversive, more original and inventive than most. His voice ranged from gratingly raw honesty to a Thurberesque humor with the ridiculous figure of the writer himself -- particularly in his role as father and homeowner -- as its object. The language was astounding, always unsettling, always shocking in the beauty for which it reached again and again, the heights and depths of emotion it attained, and the risks it was prepared to take. To describe this writing as Dostoyevskian was not far-fetched; to identify it as among the finest fiction ever written in America was, for me, a certainty.

It was an unusually troubling discovery. On the one hand, I asked myself why Fante's writing had, despite its promise, fallen so completely out of print until John Martin's last-minute rediscovery. Why had he written so little after aiming so high? Why had an audience never found an author this talented, and what did this failure say about American literary life? Which of the Fante myths was true: the story of a true talent rewarded, or the story of how Hollywood, drinking and gambling destroyed a literary gem? Or was there another, even darker story -- the tale of an artist of passion and genius who, ultimately, was not equal to his own gifts?

And so, on two separate trips to California, I collected some interviews among major figures from Fante's life, like Joyce Fante, the writer's elegant, articulate wife and his finest reader, who has so beautifully and intelligently taken care of the work as she once took care of the writer. I spent a long night talking with Linda and Charles Bukowski in their San Pedro, Calif., living room over endless Heinekens and bidis. I met Edward Dmytryk, who directed key Fante screenplays ("The Reluctant Saint," "Walk on the Wild Side"); collaborator Harry Essex, most famous for "The Creature From the Black Lagoon"; and friend and co-writer Al Bezzerides, the legendary noir stylist.

They were wonderful trips. Not the least because, even from those who held Fante personally in less-than-perfect regard -- "a personality like a buzzsaw," was the way one interviewee described him -- I never heard a word of anything other than joy for the recognition he was receiving. I came to know the Fante story so well that Paul Yamamoto, the estate's literary agent, approached me about writing the authorized biography (a job I'd have taken in a flash if I'd had an academic salary to support me while I was doing it). And I became only more convinced that Fante was a great American figure who could and should and indeed must take his place in our literary canon next to James Farrell, Nathaniel West and William Saroyan.

But I never really settled my questions about success and failure in this writer's career. And so, 10 years later, when I received "Full of Life," Stephen Cooper's new biography, I opened it with real eagerness, hoping at last for answers to the enigma of John Fante.

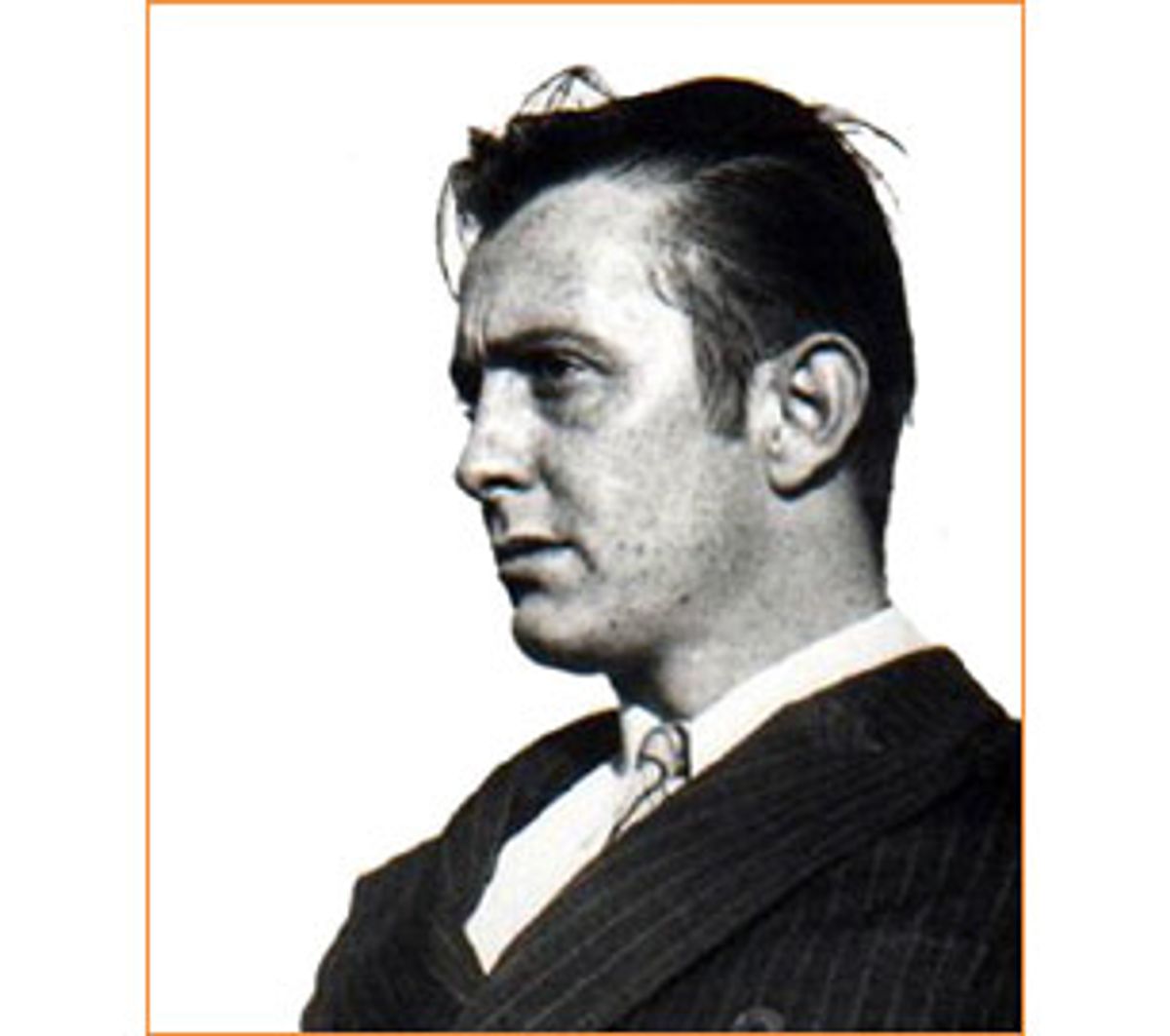

Any reader of Fante's highly autobiographical fiction knows a lot about the manic, touchy, proud, borderline-alcoholic author, a short and handsome man whose energy, at any moment directed in numerous mutually exclusive directions, was as self-destructive as it was creative. From the early works of his tetralogy about his Depression-era fictional alter ego, Arturo Bandini, his readers know the mad desire of this young man to escape his overbearing immigrant father and the deeply oppressive Catholic Church, as well as his manic ambition to be a famous writer. And we know how that boy aged into the man of the later novels: Henry Molise, a suburban father always besieged by a houseful of kids, always lost in the march of history through World War II, the years of the Red Scare, the '60s, and on into the failure of his health in the '70s.

If, therefore, the enormously painstaking biographical research that Cooper -- a professor at California State University, editor of Fante's short stories and a reader whose competence in Fante predates the writer's rediscovery -- brings to Fante's childhood and early manhood didn't much enrich the fiction for me, I still found it irresistible. This early part of the biography brims with Cooper's affection and admiration for his subject, and yet never obscures the fact that, his brilliance and talent notwithstanding, in many ways Fante was a pretty awful person: flighty, combative, manipulative and capable of real cruelty.

Cooper allows us to understand that it was not just the Depression, and not just the cruelty of literary destiny, but the man's difficult character that was evident during his long period of penury and half-crazed writing in Los Angeles throughout the '30s -- the time fictionalized in the third novel of the Bandini tetralogy, considered by many to be Fante's masterpiece, "Ask the Dust." But despite his starvation, his mania and his constant efforts to derail his own career, Fante, like Bandini, found his way. Fueled by the encouragement from afar of H.L. Mencken, his first publisher and mentor, he placed short stories in such venues as the American Mercury, Atlantic Monthly and Scribner's Magazine.

Equally important as his first publication was Mencken's encouragement to Fante to enter into the sometimes-lucrative, often dreary profession of screenwriting -- "the most disgusting job," as Fante described it to Mencken, "in Christ's kingdom." A few years after arriving in Los Angeles, we find Fante signed with Elizabeth Nowell, agent to Thomas Wolfe and Alvah Bessie, with a novel under contract to Mr. Knopf himself, and fast on his way to becoming an established writer.

But nearly none of this early success panned out. Knopf rejected Fante's first manuscript; Nowell dumped him. Then, in 1936, Knopf rejected Fante's shockingly accomplished coming-of-age novel, "The Road to Los Angeles." Vulgar, antic, challenging and unfailingly beautiful, this novel about Arturo Bandini's insanely energized climb out of the working classes toward his art would be rejected again and again, with David Zablodowsky of Viking finally recommending that Fante abandon "this vicious little satire on adolescence." Indeed, the book wouldn't be published until after Fante's death.

Throughout all this hardship, though, Cooper allows us to see that there is also a success story being told -- and not the screenwriting story. In 1938, at last, came the publication of the first Bandini novel by Stackpole Sons, "Wait Until Spring, Bandini," the volume that tells of Bandini's impoverished childhood in Colorado, struggling under the triple weights of poverty, father and church, aching to escape. Its reception was not bad at all: Praised by James Farrell and compared to Saroyan, "Bandini" was twice selected by regional papers for best book of the year. A short year later Fante published his second novel, "Ask the Dust," and if Stackpole's strange legal problems -- it was sued for an unauthorized publication of Hitler's "Mein Kampf" -- hurt the promotion of "Bandini," it is nonetheless true that, another year later, Pascal Covici at Viking published Fante's first story collection, "Dago Red," to wide praise. It sounds, when you think of it, like a pretty promising debut.

But again and again, throughout the '30s and '40s, Cooper shows us Fante snatching failure from the jaws of promise. A heroic drinker and a driven gambler, consumed by dreams of fame and ever hungry for money, Fante seems determined to dive into the exploitative depths of B-movie projects rather than pursuing the critical reputation that was, literally, within his reach. Documenting this dimension of Fante's life, Cooper is at his best, with a fine understanding of the ins and outs of the cryptic world of Hollywood deal making. And, by all accounts, Fante wrote some very fine screenplays. But his entire filmography in the end amounted to 12 titles, of which exactly three have unshared credit. His best film work, in all likelihood, was never produced.

And the 12 credits, no matter how lucrative, came at a high price. Between "Dago Red" in 1940 and "The Brotherhood of the Grape" in 1977, Fante published only a single work of fiction, and two manuscripts written during this period were rejected until after Fante's death, including "My Dog Stupid," his brilliant novella about an aging and compromised screenwriter. It was the time of the diagnosis of Fante's diabetes, during which he suicidally declined to stop drinking. It was the time when, to name one example of his stormy temper, he sent his wife by taxi to the hospital to give birth to their fourth child. It is, Cooper makes clear, the key period in Fante's life when his greatest work should have been done, and the time when his career's back was broken.

The notable exception is "Full of Life," a charming and hilarious short novel about early parenthood, published by Little, Brown in 1952. But this -- the most commercially successful piece of fiction Fante ever published (it eventually was made into a film in 1956) -- can't help but remind us, in its very airiness, of the dark, important work he failed to do during this time: Cooper aptly captures this book as a "sanitized reverse-image of the way things were with his life as a husband and father." Family life demands a great deal from Fante, and the lure of drinking, gambling and golf are never far off. Nonetheless, it is a time when he earned a great deal of money for doing some very nasty work -- 1965, for example, finds him agreeing to do a Nabokov rip-off, "Lola," for Roger Corman. And it is the time during which he described his narrator writing a novel, in "My Dog Stupid":

I could feel the blow in my gut and kidneys, sheer panic, creeping up my back and riffling the hair on my scalp. It wasn't a novel at all. It was conceived as a novel but the wretched thing was actually a detailed screen treatment, a flat, sterile one-dimensional blueprint of a movie. It had dissolves and camera angles, and even a couple of fade-outs. One chapter began: "Full Establishing Shot -- Apartment House -- Day."

And still, Fante the novelist was not done. Despite it all, somehow, in 1975, he manages to pull off that miraculous act of which so many screenwriters dream: He manages to write and sell "Brotherhood of the Grape," a novel about the death of a screenwriter's mad, alcoholic, diabetic father. The feat did not go unappreciated: Larry McMurtry in the Washington Post offered comparisons to "King Lear" and "The Brothers Karamazov." The superstar screenwriter Robert Towne -- who had encountered "Ask the Dust" while researching "Chinatown" -- optioned the book and interested Francis Ford Coppola in producing it. Was, at last, the recognition Fante had so long deserved going to come to him?

If so, it was coming too late. Having suffered from diabetes since the '50s, John Fante lost his eyesight in 1978 and began a steady descent into the cruel last stages of this disease that would end in the amputation of both his legs. And, at last, came the rediscovery of his books, thanks to Bukowski. "Out of respect for his idol," writes Cooper, "Bukowski had never dared approach Fante." Fante was blind when "Ask the Dust" was republished in 1980. And still he managed to close the Bandini tetralogy by dictating "Dreams From Bunker Hill" to his wife, in 1982. He died in 1983 at 77, following which both the unpublished work and the entire life's work were brought out again by Black Sparrow, and the Fante story came to be, as we know it today, a literary morality play quoted when the conversation turns, as it inevitably does, to the serendipity of literary life -- a writer whose story, somehow, has become better known than his stories.

So what, in the end, is the meaning of the John Fante story? Is it really a story of a great writer denied his audience? Is it really a tale of talent finally triumphing?

Yes and no. Sure, great art should have an easy path in the world. But the fact is that in writing, as in music, there is more talent out there than there is room in the machinery of publishing or in the public's attention. This being the case, the inherent difficulty of being an artist will always carry the ancillary frustrations of finding an audience. And sure, there is always luck involved. What if, for example, Bukowski had seen fit to acknowledge his debt to Fante in, say, the mid-'60s rather than the late '70s? There would have been a good 17 years of writing time available to Fante -- had he wanted to take advantage of it.

But would he have? In the end, Stephen Cooper's fine biography makes it hard not to feel that the opportunities were always there for John Fante -- many more opportunities, in fact, than he knew quite what to do with. And it's hard not to feel that more than a story about the fickleness of audiences or publishers, the story of John Fante is of a writer who, in a key period of his life, failed to wrestle his talent to the table. He failed because of whatever it was in his mind that kept him suicidally drinking, gambling and fighting his way through his life. My night with Bukowski and his wife started at 8 p.m. in a San Pedro restaurant and ended in their living room sometime just before dawn. A portion of the night's talk is on tape, and that part I can refer to today:

[What caught me in Fante was] when he was alone and starving and trying to be a writer in a tiny room ... Starving for your art for Christ's sake. That isn't done much nowadays. Seems like more in centuries past, guys would starve for their art. They'd go mad for it, throw everything up to be able to create ... People won't give up their comforts, they won't take the big risks. People want [the] name, they want fame, but they won't lay down their blood for it, they won't go mad for it, they don't have the passion for it. They want the reward, but they don't really have the inner drive to really do the thing that they want to be famous for.

Now, listening to the late poet's flat Californian voice sounding on my stereo, I wonder about that. It's striking that, for all Fante's calculation and attempts to engineer a writing career, the real fiction came by itself and survived by itself, and had he, like Bukowski, never done anything but pursue his art, he would likely have been the famous writer he dreamed of becoming.

When I think of it, I can nearly get angry. I can nearly feel that, like a farmer holding land in trust for a generation, Fante held a gift bigger than himself, the ability to make some little sense of the enigma of existence, the chance to capture the country he witnessed riding freights down the West Coast in the '30s, in California in the '40s, in the rich sounds of his Italian parents and in the sights of their immigrant world. Artists face incredible odds -- think of fellow Californian John Sanford, who has pursued his talent in the face of nearly universal rejection over nine decades, and he's at it still.

But perhaps, in the end, none of that matters. What matters is that there are 10 volumes of Fante's writing on my shelf, and two volumes of his letters: always in print, always there to be rediscovered, as I discovered them.

And perhaps it is not such a terrible thing to say of Fante that his readers will always close his books, not only grateful for the strange luck that allowed these books to survive, but also regretful that this angry and wonderful man never quite had what it took -- call it courage; call it luck; call it faith -- to follow his vast talent, like Bukowski did, all the way to the end.

Shares