On Nov. 23, moments before a Northwest Airlines jet was scheduled to depart Las Vegas for Detroit, the captain let his belly get the best of him. The Minneapolis Star Tribune reported that the pilot was upset because his "special meal" had not been delivered. "He got off the plane, he walked by a number of food establishments that were open and serving, he got into a cab and went off-site," said Northwest spokesman Jon Austin. While searching for a meal that would please his palate, the finicky flyboy managed to delay Flight 1194 for more than an hour.

It took less than two weeks for airline management to terminate the captain. Like the special meal he so desperately desired, his 22-year flying career was consumed, digested, flushed down the toilet and forgotten.

Though such reactions are rare, food -- or the lack thereof -- is as volatile an issue for crew members as it is for airline passengers. Some union contracts require that airlines provide on-board meals for pilots. At Delta Airlines, where pilots have no such provision, the company recently announced a voluntary program to spend $3 million to $5 million for cockpit crew meals on flights where food is served.

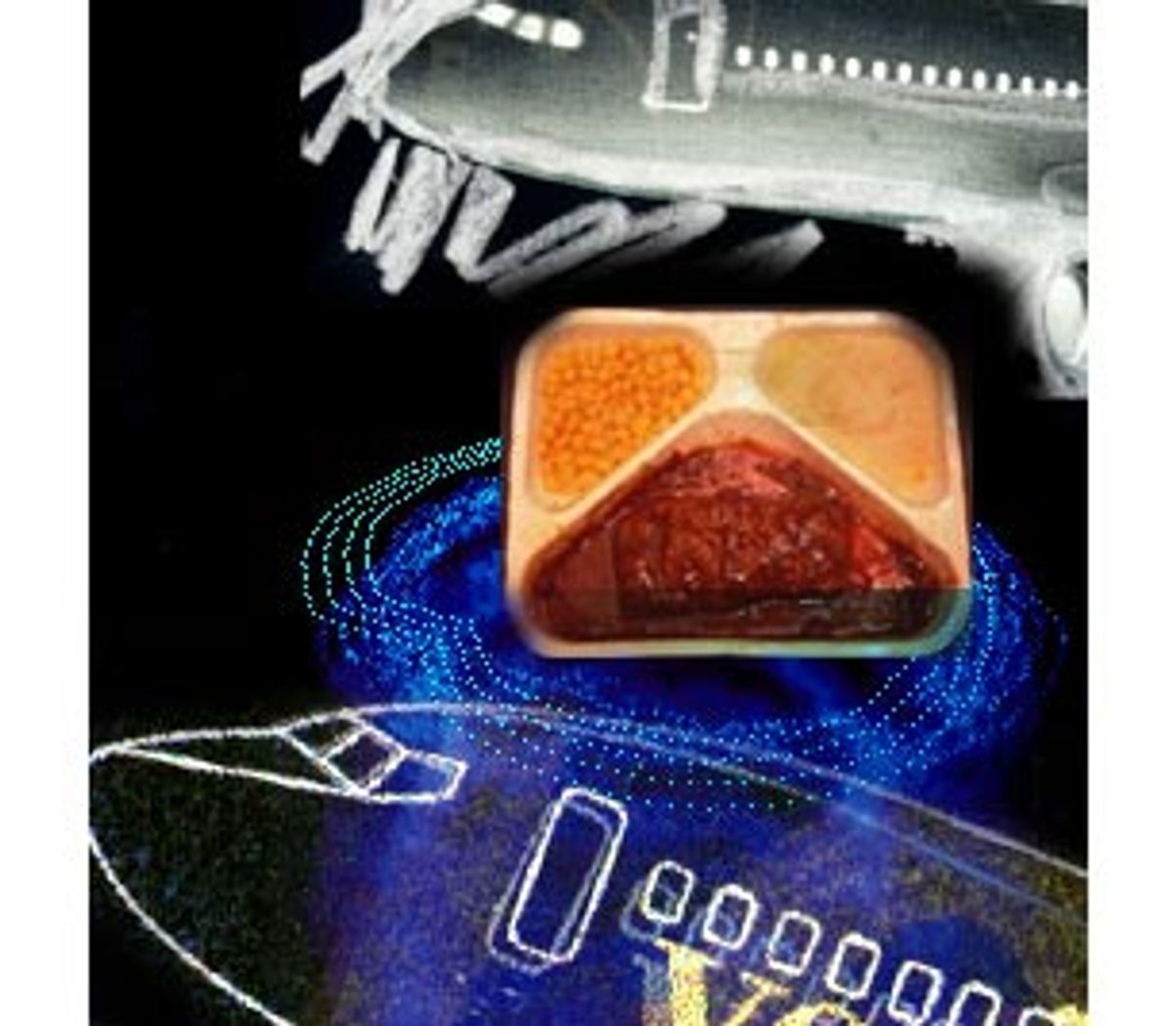

Flight attendants at most carriers have no such luck: Unless we happen to be working on a long-haul international flight, there's usually no food designated for cabin crew. And during long, multileg flight sequences, when flight attendants are on duty for up to 14 hours and quick connections require sprints from plane to gate to plane to gate, three, four, sometimes five times a day, there simply isn't time to eat on the ground. Often, there's not enough time to stand in line for a takeaway quarter pounder at an airport McDonald's. When time is short and hunger opens a crater in a crew member's stomach, we rely on the old standby: leftover airplane food.

After the passenger meal service has been completed, flight attendants often gather in the first-class galley. We don't just come here to chat, however. When we disappear into the galley, we mean business. Like vultures hovering over the half-eaten corpse of a wildebeest, we lick our beaks, lusting for an appetizer or a dinner roll, hoping to snare some leftover meat -- all the while praying that our comrades are on a diet. If there aren't enough entrees for the entire crew, someone might make a halfhearted offer: "Wanna split this with me?"

"Oh, no, no ... that's OK," a polite, starving colleague might respond. "I'll see if there's any food left in coach." But the good folks at airline catering have gotten much better at matching the number of entrees to the number of passengers. After all, it's the catering company that ends up paying for extra meals. If every passenger decides to eat, and the plane has been stocked with the appropriate number of meals, the main-cabin galley ovens should always end up empty. So will the stomachs of luckless crew members who fail to bring food from home.

Packing your lunch before setting off for work is no big deal if you're working at an office or a construction site. You make a sandwich or wrap up the previous evening's pasta and you're in business. But for flight attendants, especially those of us who work three- and four-day trips, it's difficult to pack food for the duration.

Still, I've flown with co-workers who lug their own food through six countries in three days. Inside their special bags, you'll invariably find the potato, the perfect food for crew members on the go. It's healthy, durable and can be heated up in the galley oven. Homemade lasagna, sandwiches, bags of fruit, Tupperware containers filled with pasta or tuna salad -- these are favorites of the polyester jet set.

Trouble is, the U.S. Customs Service won't always allow food into the country. Even if the food is prepared in Texas that morning, once you get on a plane and fly to, say, Central America and back, the very same food is subject to importation restrictions. Many a flight attendant is guilty of smuggling food past narrow-eyed customs officials.

Don't think for a minute that flight attendants aren't sensitive to passengers' concerns about airplane food. Few travelers understand the problem better than we do. We've heard the complaints two or three thousand times. We know the portions are too small. We know the chicken is sometimes as bland as petrified tofu. Like you, we question whether that paltry piece of in-flight steak/gristle actually comes from a cow. During short-haul domestic flights, we're embarrassed when we have to say "I'm sorry, but there's no meal service. All we've got are peanuts and drinks."

If it were up to flight attendants, every main-cabin passenger would dine on lobster, prime rib or the very best vegetarian creations. We want you to be well fed. Well-fed passengers are happy passengers. And happy passengers make our job much easier. Besides, we get your leftovers.

After listing to our grumbling stomachs for years, my airline began providing flight attendants with snacks. Delivered in individual plastic bags, the snacks are catered on certain flight sequences that make it difficult, if not impossible, for us to grab lunch or dinner. The company calls the bag of goodies a "Snack Attack." Or maybe it's a "Snack Pack" or "Snack in a Sack." Or some cutesy moniker hatched in the brain of an airline executive who wouldn't dream of eating this stuff.

Inside the bag there's usually a main course. Sometimes it's a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. Other times it's a carton of just-add-hot-water vegetable soup. The broth is drinkable, but the vegetables taste like morsels of soggy cardboard. The main course is accompanied by an apple or orange, and maybe a couple of crackers. Cookies too: in short, everything flight attendants need to get through a 14-hour day.

Shares