After police shut down Serbia’s four leading independent media outlets, the early rumblings of civil conflict seemed closer at hand in the capital on Wednesday. The day’s events could mark an end to the tense status quo that has existed under Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic for the past several months — or it could mark the beginning of an even more repressive dictatorship.

Just before dawn on Wednesday morning, secret plainclothes police and technicians with black wool face masks stormed the offices of independent television Studio B and independent Radio Free B292, pulling news broadcasts off the air and padlocking the offices. The police also shut down student Radio Index, and the top independent daily newspaper “Blic.”

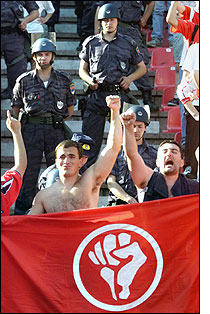

Approximately 30,000 angry Belgrade citizens demonstrated in front of the city assembly building later that day, before being charged by Serbian police in full riot gear Wednesday evening. At least five people were injured. Exact figures of arrests and injuries were difficult to compile in the media blackout.

The closure of Serbia’s top four independent media outlets follows weeks of increasingly violent rhetoric from Milosevic against Serbian pro-democracy forces. Milosevic has singled out the student group Otpor, whose name means resistance, as well as the political opposition and the independent media that bore the brunt of Wednesday’s crackdown.

On Wednesday evening, state technicians blocked the transmission of Radio Pancevo, the last independent radio network that could be heard in Belgrade, leaving the capital in a media blackout.

Shortly after police seized Studio B television, it broadcast

a recorded message saying that the Serbian government had decided to take

over Studio B, because the opposition-controlled station had been

calling for the overthrow of the Serbian government. Since its seizure,

Studio B has been broadcasting programming from state-controlled

Radio Television Serbia. The message said orders for the seizure were signed by Vice President Milovan Bojic and the far-right nationalist Vojislav Seselj, a member of Milosevic’s ruling party. Late Wednesday night, state-run Radio Television Serbia aired an English-language movie about a Nazi collaborator.

After it was shut down, Radio Free B292 immediately resumed broadcasting on the Web and via satellite from Bosnia, but few Serbs have access to either the Internet or satellite TV.

About 300 journalists and staff members of the closed independent media stations stood outside their padlocked offices in the brilliant May sunshine Wednesday afternoon. They talked with each other on mobile phones, smoking cigarettes as the Serbian secret police gathered in the city center to observe the scene. Watching in plainclothes from nearby cafes, some carrying shopping bags and hoping to fit into the crowd, the dreaded State Security Service secret police kept a close eye on those preparing protests in the city center. Independent journalists and tens of thousands of angry citizens gathered at City Hall in the early evening. Their protests gathered nervous energy from thousands of rowdy soccer fans, high (and some drunk) on the victory of Belgrade’s Red Star Football club.

Otpor said 11 of its members were arrested Wednesday, following weeks of stepped-up harassment. The student group has become increasingly popular among the Serbian public in recent weeks, in part because it is not associated with any political party. The Serbian public has become weary of politicians, both regime and opposition alike.

With no leadership hierarchy, no unseemly political infighting and with a defiant sense of humor, Otpor has emerged as a broad-based, grassroots network, attracting the respect and allegiance of the war-weary, anti-government Serbian public. The group’s demonstrations are doubly subversive for being humorous.

Last weekend, on State Security Day, Otpor sent an ironic message of “congratulations” to the Ministry of Interior, and the students delivered flowers and letters to on-duty police officers who have been busy arresting Otpor activists. Other pranks have included “the fast trains of Serbia,” a parody of a postwar reconstruction program by the regime to rebuild Serbia’s railroads. Otpor set up electric trains with one track redirected to the Hague, a reference to the fact that last May the U.N. War Crimes Tribunal in the Hague indicted Milosevic for crimes against humanity. Otpor activists have also called on Milosevic to “Save Serbia, kill yourself.”

In response to the group’s growing esteem, the Milosevic regime has accused the group of being “terrorists,” “fascists” and Nazis — demonizing them in language even harsher than it used last year to paint the Kosovo Albanian rebel force, the Kosovo Liberation Army.

On Monday, posters began appearing around Belgrade of a Nazi soldier with his arm raised in a Hitler salute with the clenched fist that is Otpor’s symbol of resistance. The poster reads “Madlen Jugend,” referring to U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and the German word for Hitler Youth. The Milosevic regime has launched a campaign to systematically portray Otpor and Serbia’s democratic opposition as domestic agents for the United States and NATO countries that bombed Serbia last year.

“The aggressor is placing his weapons in the hands of domestic servants in order for them to do their dirty work, to spread fear and chaos,” said Gorica Gajevic, secretary general of Milosevic’s Socialist Party of Serbia, this week in the state-run newspaper Politika. “They want to set Serbia on fire; they are attempting to topple the authorities with violence, to provoke street unrest, to incite a civil war.” He went on to call Otpor “traitors and criminals,” and threatened the regime would deal with Otpor “just as it has dealt with every other evil.”

For days, the Milosevic regime has been signaling that a serious crackdown was imminent.

When Bosko Perosevic, an official from Milosevic’s SPS Party, was gunned down Saturday at an agricultural fair in the northern Serbian city of Novi Sad, officials close to Milosevic’s ruling coalition immediately accused Otpor of being responsible for the assassination.

Although this was one of the rare recent assassinations in Serbia for which the assassin was immediately identified and caught, the regime claimed that they found literature from both Otpor and the opposition political party of Vuk Draskovic, the Serbian Resistance Movement (SPO) in the gunman’s apartment. Otpor and the SPO both deny that the gunman, Milivoje Gutovic, 50, was a member of their organizations. They say Serbian police have confiscated much of their material and probably planted it in the man’s apartment.

A week before the assassination, bodyguards for Milosevic’s 26-year-old playboy son, Marko, viciously beat up three Otpor members at a cafe in Milosevic’s home town of Pozarevac. Two of the beaten students are being held in Serbian prisons, despite the fact that witnesses confirm their claim that Marko’s bodyguards attacked them.

That came a few days after Marko reopened his Bambiland theme park for its second season of business. The $7 million Disney-style amusement park was built during the NATO bombing last year, when all the state’s resources were supposed to be devoted to defending the homeland. Some in Serbia suggest that the animosity stems from Otpor’s satirical attacks on the ruling family’s nepotism, and the stealing and killing it has unleashed.

Serbian opposition leaders warn Serbian citizens that if they don’t resist, Milosevic will usher in an era of open dictatorship.

“Support the opposition and Studio B,” Studio B Television’s director Jugoslav Pantelic urged demonstrators Wednesday night in front of city hall, urging them to stand up to Milosevic’s “fascist-communist” government.

“The regime has taken the country into a state of emergency,” opposition political parties wrote in a joint statement. “Let us stand against this violence with all our energy because the future of our country is at stake.”

But without independent media left to broadcast their message, it is unclear how pro-democracy forces will now reach the Serbian public.