The panel at the Art Directors Club on 29th Street in Manhattan was just getting into an interesting discussion about fashion and status when the impatient, standing-room-only audience started getting antsy, downing drinks and conversing loudly. The fashionable crowd had assembled for a party to celebrate the release of "Material Man" -- a collection of essays on "Masculinity, Sexuality and Style" -- and the exhibition accompanying it (which closed Saturday). But the sound system lacked clarity, and the discussion seemed unfocused, ranging from topics like tattooing and male jewelry to Brooks Brothers and ambivalence toward fashion. By the time the book's editor, Giannio Malossi, took the stage, the din in the room was too much to bear, and the panel quickly broke up.

Lack of clarity and purpose can do that to a crowd -- and to a book. Supposedly a rumination on the influence of style on masculinity and sexuality, the book is less about its text than its photographs, despite the large number of essays from academics such as Valerie Steele and Alain Weill. It is these photographs -- including those of individuals from a smiling William Jefferson Clinton and Rudy Giuliani (in drag) to Lou Ferrigno and Evel Knievel -- that, at times, make "Material Man" so compelling. Unfortunately, the book's producers got a little carried away and, instead of sticking with one theme, went after three of them, making the book about as easy to read as having (or hearing) a coherent discussion amid a liquored-up crowd at a book party.

Masculinity

"Material Man" is undeniably male, from the cover image of a man's suited torso in shades of blue and orange -- a "masculine" color combination associated with industry and sport -- to the book's ending, a full-page photograph of Sean Connery as James Bond in "Goldfinger." There are, of course, the requisite photos of guns and urinals, of motorcycles and facial hair and groins. And there are the not-so-expected images, like the series of black-and-white photographs of Mexican wrestlers or the colorful (and phallic) designs for razors, cars and power drills.

The masculinity on display is interesting, but, as explored in the text, it's nothing new. The book offers no real investigation into issues of class, age or race. (There are only three black men in the entire book -- Muhammad Ali and two naked African tribesmen.) The sort of pretentious, say-nothing philosophizing that informs the first few essays in the book finds its nadir in the essay "There Is a Savage in the Future of Man," by Italian psychoanalyst Claudio Rise.

Rise posits that post-World War II culture has produced a kind of sissy man, a male emasculated by modern society and commerce. (Corporations represent "the figure of the Great Mother" and tend to "break the emotional and symbolic unity of men.") The modern male Rise decries is a male unable to create "new forms," "new actions" or "crazy ideas," a male suffocated by society, which (like a woman, he intimates) has as its prime goal "the maintenance of the individual and the satisfaction of his or her needs." Rise throws around terms like "female receptivity" (negative) and "gift of phallic force" (positive) like some kind of 1950s Freudian freak, and the whole essay is completely insulting, both to women and to the book.

Luckily, Rise's essay is followedt by industrial designer Anna Lombardi's hilarious "Sex Objects: Portrait of a Real Man." This brief but ballsy bit of sarcasm deftly skewers both the lowbrow idea that masculinity is a commodity that can be purchased (that a Ferrari will make you a real man) and the highbrow psychobabble that accompanies such objectification (that a Ferrari is an extension of your penis). It is just her sort of humor, insight and accessibility that much of "Material Man" is lacking.

Sexuality

When it comes to sex, "Material Man" doesn't truly give it up for its readers. (Yes, we know Mel Gibson is "sexy," and so was Robert Mitchum.) In fact, the most exciting part of the book, sexually, is the strange eroticism in "Men of Marble," a suite of photographs of male sculptures by Roberto Schezen.

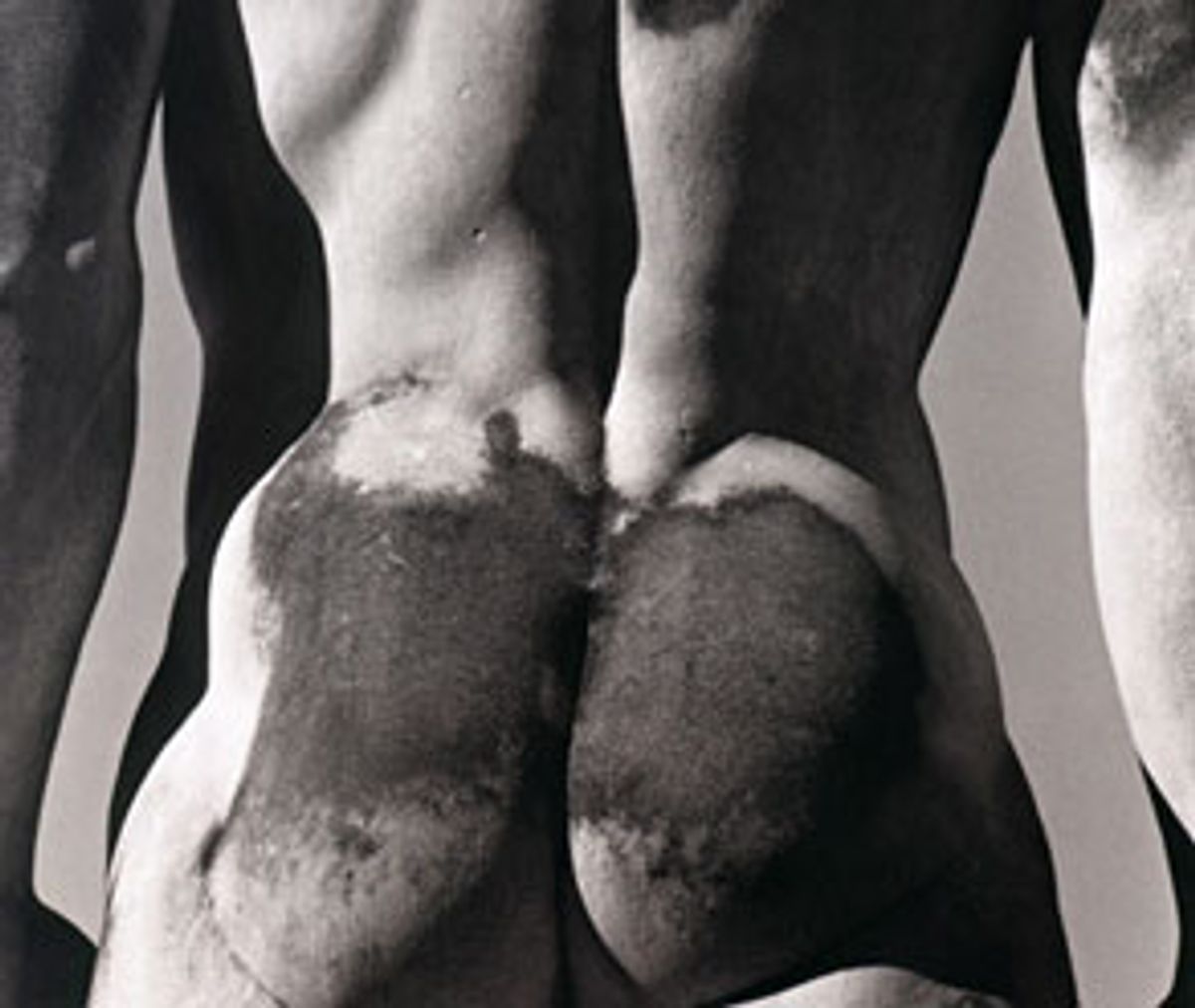

Shot at close and compelling angles, these images are overtly erotic and filled with more life and light than any of the Armani models or publicity stills of old movie kings that appear on preceding pages. The opening shot, in fact, almost took my breath away: a close-up of the naked backside of a stone male, his ass muscles clenched and at the ready, his back widening at the shoulders, the stone itself darkened in places to suggest that -- were he animate -- he had just arisen from resting naked on his back in wet sand.

Schezen's photos concentrate on the lower belly, that soft space framed (and often upstaged) by penises and rippling racks of abdominal muscles. And what a sexy space it is, feminine in its curves, masculine in its musculature. Michelangelo knew just how to sculpt it; Schezen knows just how to shoot it.

Besides "Men of Marble," however, the book has little to offer when it comes to sexuality. Certainly, the photo of Lenny Kravitz in a pool is sexy, but it's sexy with a capital "S": styled sexy, self-aware sexy, tattooed and pierced and bare-chested "rock star" sexy. There are lots of bare chests in "Material Man," and penises, of course, but the chests are attached to runway models and the penises are all small and nonthreatening, or ugly, or attached to ugly men. And what about homosexuality? The book hardly touches on it, although gay male culture has always strongly informed straight male culture and style. The lack of exploration into male sexuality -- straight and gay -- makes "Material Man" seem like the kind of superficial coffee-table book your typical Fortune 500 homophobe will feel comfortable displaying on his yacht this summer.

Style

So this is what it comes down to: "Material Man" is not a book about masculinity or sexuality but a book about style and the media. To be fair, this is precisely where it succeeds -- from the images of crew cuts, Tim Burton's "Batman" and military uniforms to Alix Sharkey's hilarious and informative essay, "New Media, New Men" (about the rise of saucy men's magazines like Maxim and FHM).

For style it's worth a look. (After all, "Material Man" is the creation of an Italian fashion research center, Pitti Immagine.) But for anything real about masculinity or male sexuality, you're better off plowing through the latest Susan Faludi or Camille Paglia. Because although the fashion industry sells it in spades, fashion itself has rarely been about sex -- real sex -- and it has rarely been about masculinity. "Material Man" is a sobering reminder that superficiality still reigns when it comes to style.

Shares