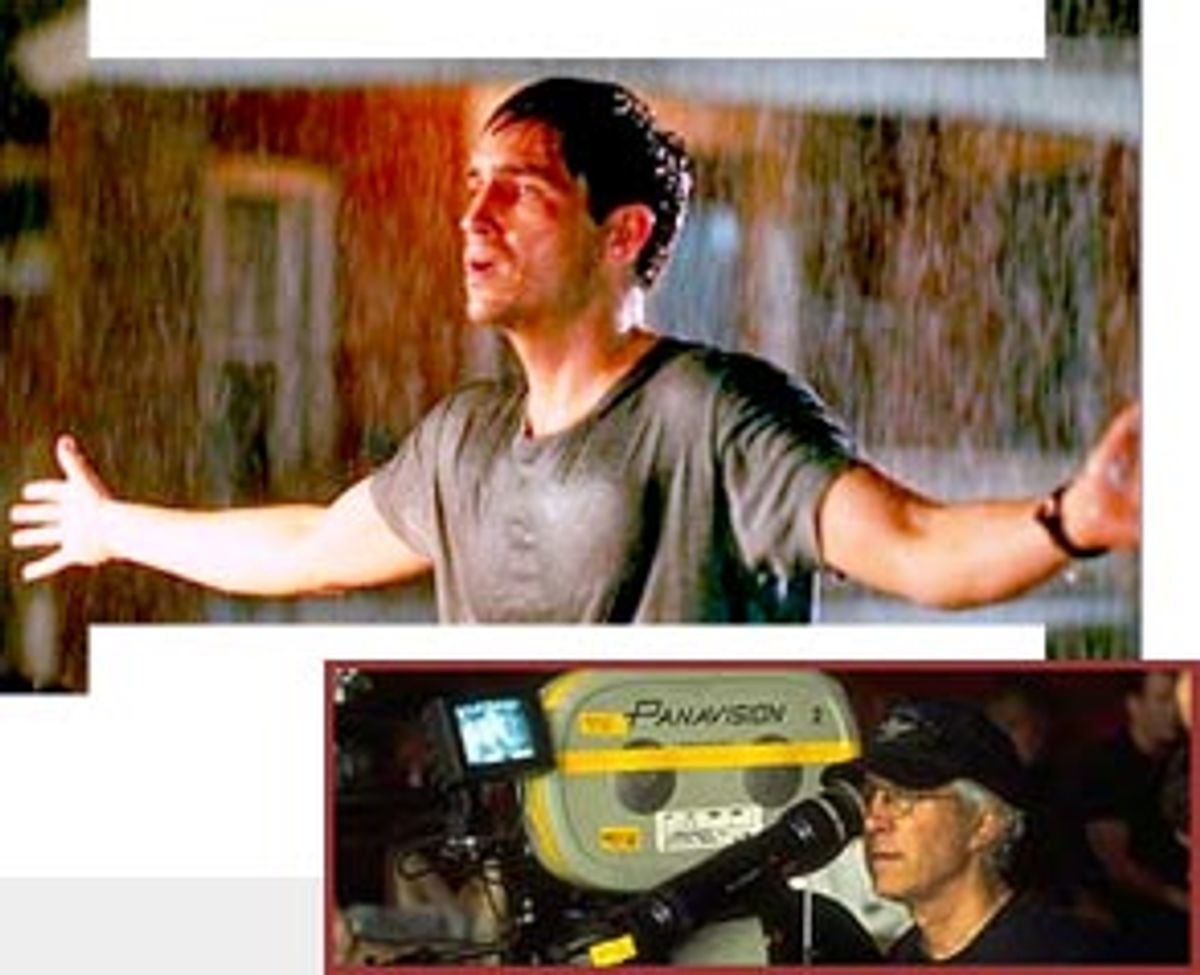

The stealth box-office winner last week was Gregory Hoblit's

"Frequency," a skillful fantasy-thriller-tearjerker about a melancholy

36-year-old cop (Jim Caviezel) who dusts off a ham radio set that was the

joy of his late fireman father (Dennis Quaid) and finds himself talking to his

dad. (On the son's side of the conversation, it's 1999; on his dad's, 1969.)

"Battlefield

Earth," in its second week, plummeted a whopping 67 percent; even the

mega-hit "Gladiator,"

in its third week, dropped 23 percent. By contrast, "Frequency," in its fourth

week, fell off a mere 13 percent. Watching the film with a nearly full house

late on a Friday afternoon, I only wondered that it hadn't gained even more.

I think Bruce Diones of the New Yorker hit on the film's appeal when he

wrote, "Hoblit's camera lingers on the actor's faces, and the aggressively

emotional performances feel authentic; the film's blatant heart-tugging is

earned."

What grips even skeptics about "Frequency" is its combination of sincerity

and dexterity. Hoblit and his screenwiter, Toby Emmerich, survey the same

landscape as "Field of Dreams." But Hoblit keeps the textures edgy, and

Emmerich keeps the action unpredictable, entwining sci-fi motifs about time

warps and "string theory" with a race to find a serial killer and a nostalgic

look at the 1969 Mets. Quaid, with his wounded brand of regular guy-ness,

and Caviezel, quivering yet still manly, have a father-son chemistry that's all

the more intriguing for being slightly off, while Andre Braugher anchors the

supporting cast in both the 1969 and 1999 stories with a sage turn that's an

about-face from his firebrand role on "Homicide."

As he did in his 1996 debut movie, "Primal Fear" -- the murder mystery that

made Edward Norton an overnight sensation -- Hoblit shows the savvy and

the instincts of a true popular entertainer. (In between came the Denzel

Washington misfire "Fallen," an attempt to drop a demonic horror plot into a

copland milieu.) Why should we be surprised at Hoblit's deftness? After all,

he honed his talents in years of supple work on "Hill Street Blues," "L.A. Law"

and "NYPD Blue":

TV series that kept moviegoers out of the theater and glued to the small

screen. What I didn't realize until I spoke to Hoblit on the phone two weeks

ago is that he was uniquely qualified to depict public servants on screen. His

father was a paramedic in the Army Medical Corps during World War II and

later joined the FBI, in which he served for 26 years. Born in Abilene, Texas,

when his father was stationed with the Army there, Hoblit grew up in

Berkeley, Calif. He attended public schools and UC-Berkeley -- before joining the

merchant marine and switching to UCLA.

Growing up in Berkeley, did moviemaking seem like an real career to

you?

We were surrounded with people teaching at the university or somehow

involved in it; it was natural that one would have the notion of becoming a

doctor or a lawyer or a professor. And my dad was in the FBI until 1970. I

grew up with FBI men and cops; I was comfortable in that world. But I loved

the movies. My father would give me 25 cents to rake the leaves or mow the

lawn every Saturday, and I would take it and go to the movies, usually

alone, since none of my friends were really interested.

When did you leave UC-Berkeley and move to UCLA?

It was around 1966. Because I was very politically active, and my father was

a big gun in the FBI, it was difficult for me to be at UC-Berkeley, and difficult

for my father. J. Edgar Hoover, who was running the FBI at the time, was

rather quick to transfer people, if it suited his whims. While me and my dad

didn't agree on anything politically, he was a really good guy who had

worked hard and honestly throughout his life to keep doing what he was

doing. I didn't feel it was my journey in life to disrupt his life any worse than I

already had, or that it was his responsibility to pay for me to act on my own

ideas and agendas.

In order to make enough money to go to school away from home I joined the

merchant marine. That was the beginning of three-and-a-half years of sailing

during summers and different vacations, on freighters and on tankers. Jeez, I

could get on a ship and walk off three months later with $3000 cash in my

hand. I was honoring a lifelong fantasy -- from having read "Billy Budd,"

"Moby Dick," and a lot of Joseph Conrad -- of going to sea. I grabbed a

couple of ships and went to sea -- went to Japan and China and the

Philippines and around South America. I cabled my parents from Japan, I

think it was, to see if I could get transferred to UCLA. They cabled back that

it was possible.

I have a story in my head that I'm close to organizing about my life in the

merchant marine; it has pirates and all the other adventures you encounter

when you're out there. It's an amazing world. And when I was a 20-year-old

banging around in it, it changed my life in a profound way.

Were you still as political when you got to UCLA?

No, I kind of burned myself out politically. When I went down to UCLA I was still an undergraduate. There I ran full into people from the theater-arts department and began to go to the twice-yearly screenings of student films. And I loved to go. So I made a Hail Mary attempt to get into the film school when I was closing in on graduation -- and I got in. This was around 1968. Things began to happen, partly by design, partly by happenstance, but all of them with a clear focus to make films of some kind. I was interested in documentaries, in television, in movies.

Coppola and others had already been through there by then. Did it make you feel you could actually get somewhere in the industry out of film school?

To me, when I was young, film school was on Mars, not Earth, and film students were Martians, not people. I went at it carefully and with some distrust, because the level of bullshit was huge. It was stupefying to stand around hearing people talk about their summer internships and the directors they were going to be working with and the movies they were going to be involved in. The intense-wannabe atmosphere was pretty suffocating.

When I heard all these people talking about internships that never happened, I decided I better get the first job that I could that was real. That turned out to be a job as a gofer on the old "Joey Bishop Show," which you probably don't remember.

Yes I do. Regis Philbin was the cohost!

That's right: Good for you! It was on 11:30 at night, and I was booking novelty acts and getting sandwiches for Zsa Zsa Gabor. I'll tell you: in the six months I was there, before the show went under, I learned more about organized chaos and what went into making something behind the scenes than I had in a year and a half at UCLA. I was seeing how pros took care of business. I knew I would never go back to school full-time. When the next opportunity came my way, which was actually borne of that Joey Bishop job, it was a call from ABC in Chicago to associate-produce some talk shows. I'd sailed around the world, yet in this country I'd never been east of Nevada. But I went to Chicago and dived into talk television -- a morning show and a late-night show. Again, it was getting in there and rolling up your sleeves.

Still, my heart lay in telling stories -- I'd write letters home about what was going on with me in Chicago, and I'd get a lot of feedback saying that I should think about writing. And I did some writing when I got back to Los Angeles, in 1972, along with working on a half-hour comedy show and co-producing two low-budget features.

I was wondering how Chicago figured in your work; some gritty filmmakers (William Friedkin, Philip Kaufman) come from there.

Well, the ode to Chicago is "Hill Street Blues." The opening title is of the Maxwell Street Precinct in Chicago, Maxwell Street and Halsted in Chicago. And all the establishing shots and the cop cars zipping through the streets here and there were shot in Chicago.

I remember always thinking, when I watched the show, "What city is this?"

It was fun, because the first several years -- before people got onto the fact that it was Chicago, in the main, because they figured out that the cop cars were the same color as Chicago police cars -- people in Baltimore, Detroit, Boston, Philly, all thought it was their city. We purposely did not designate a city: We wanted it to be any big city where there was weather, where you got rain and snow and a sense of urban decay. The Hill itself was named after an area in Pittsburgh: a tough area called the Hill and the precinct there. Bochco had gone to college in Pittsburgh, at Carnegie[-Mellon].

So how did you hook up with Bochco?

Zigs and zags. There was a prominent Northern California guru who at the time was known as Bubba Freejohn -- he has several different names -- and he had a rather well-known commune around Clear Lake, Calif. My former roommate at UCLA and his wife had encountered this guru and asked if I'd come up and shoot a week of celebrating up at the commune. I had nothing else to do so I did.

The ex-husband of my girlfriend at the time had been Steven's roommate at college. So when I made this 43-minute documentary my girlfriend invited Steven to come and see it. And Steven thought it was kind of extraordinary. He was interested in the film techniques. He laid out an open invitation that when I was ready and interested, I should give him a call. It took me about six years to get around to that. During that time I wrote and did little things to keep afloat. I called him in '78 and said, "I'm ready to come in from the cold." And he was gracious and generous. We were together for a long time -- and still are in spirit.

What excited Bochco about your documentary?

You'd have to ask him. But the camera was a very active participant -- not unusually, for documentaries -- and I mixed in slides and 8mm stuff I found. I used different kinds of film stock to emphasize day or night or the mood of a scene, and music was very important to it. It wasn't bleak and it didn't just look into the commune, it was a filmgoing experience. At least it worked that way for Bochco.

He put you in touch with people at Universal, and you became involved in, among other things, associate-producing the TV-movie version of the Marvel Comics character "Dr. Strange." But when did you start to work directly with Bochco?

Eventually, Steven left Universal, and at Grant Tinker's inducement went over to MTM. When Universal came to me with a five- or seven-movie deal to begin producing for them, I called Steven and said, "I don't really want to do this, do you have any wisdom for me?" His wisdom was, "Come work with me." I moved to MTM, where we did a half-hour presentation of a show called "Every Stray Dog and Kid" that did not succeed -- but we met David Caruso and Mickey Rourke. We did a movie of the week called "Vampire," which was a lot of fun. Steven had written it with Michael Kozoll -- they'd been writing together for [the writer-producers] Levinson and Link, things like "Columbo." And we made a short-lived series called "Paris" with James Earl Jones -- 13 episodes and off the air. It was a noble try. It was a little dated in style and mechanics, but what it did do was put a black man front and center as the lead in a drama.

But then Steven and Michael Kozoll hatched the idea of "Hill Street Blues." The two of them pulled out of their war chest these various characters that they were never able to use, like Bruce Weitz's character Belker, or Michael Conrad's character Esterhaus, or James B. Sikking's character Hunter, characters they couldn't use in the conventions of normal television, but that in the world of "Hill Street" were all possible. They wrote the script and sent it to me, to get my ideas on how I would produce it with them, and it was everything I wanted to do. It was going to allow an active camera, with a personality of its own, and create a world that you could almost taste, smell and feel. We were going to break the rules of fastidious television. You'd see sweat, wounds. You'd have people talking in half-sentences and interrupting each other. You could do a scene in one big shot instead of a whole bunch of little shots. Michael and Steven painted this rich canvas in words that I was able to take and with a director named Robert Butler, a kind of renegade himself, transform into the film that became the "Hill Street Blues" pilot -- or, as it originally was called "Hill Street Station."

Were you initially, in movie terms, the "line producer?"

Yes, I was, but I had a very strong sense of that show's textural qualities. I

became increasingly involved in all the creative aspects of it, including the

scripts, and even wrote one or two. I was very involved in the rewrites -- in

the sense that I would say to Steven, "If you want a scene to look this way on

film, this is how to write it. The words are great on the page, but this is what

you have to do to make them into great film."

At the time of their premieres, "Hill Street Blues" and "NYPD Blue" were

considered iconoclastic in their treatment of police departments. But they

really weren't debunking police -- they just made a viewer go through more

to respect these cops, so you had an honest respect for them instead of just

a reflex.

I think that's true. And of course the credit goes first to Steven and Michael

and in "NYPD Blue" to David Milch and Steven. We all had great regard for

those professions. But the shows weren't about "cops," they were about

people who happened to be cops. Anymore than "L.A. Law" was about

"lawyers," but was about people who happened to be lawyers. The idea was

you couldn't help but be involved with people whose lives informed what

they were doing -- people who informed their work with who they were.

There was always a circular aspect to it that made them richer and more

honest as characters.

"L.A. Law" was a more conservative show than either of the cop series,

at least visually.

I think that content determines form. "L.A. Law" was much more

conventional, not so much in the storytelling but in the way it felt on the

page, in its words. I knew it was as much of an uptown show as "Hill Street"

had been a downtown show. It was more classical -- elegant, brainy -- and

the people it was about had more money. I knew I would shoot it in a much

more normal way. When it came to "NYPD Blue," my first response was that I

didn't want to direct it -- I didn't want to do "Son of 'Hill Street.'" But when

Steven asked what I would do if I could bring myself to do it, I said this is the

kind of visual style, and music and editorial style that I would give to it. And

he said OK.

I knew it would rattle him! Steven is not as prepared to go off the deep end

as I am. We banged heads a lot over the style, but he honored his

agreement with me. He didn't like the camera zooming around but he agreed

and he stayed by it. The technique had a lot to do with the pulse of the

piece. If there was a relaxed scene, the camera might relax, but if there was

a scene filled with anger and tension and fear the camera would reflect that.

Didn't "Homicide" do a lot of that?

That's always a point of a little bit of conflict between ["Homicide" creator]

Tom Fontana and me. We had done it; "Homicide" got out on the air before

us. They were really handheld. They did all kinds of ballsy, in-your-face

things, which I applaud. I found it to be, however, their own worst enemy. In

the beginning it was so jumpy, so self-conscious, so much so that you

stopped listening to the story and the words because you were dazzled by

the footwork.

I had lit on the style after seeing some commercials, particularly by a really

famous and extremely well-regarded commercials director named Leslie

Dektor. Dektor was doing the 501 commercials, the AT&T spots, and that

camera was moving, and roving. And Dektor gave it a kind of elegance: The

movements were so subtle, you didn't know what was happening with the

camera unless you were really paying attention. I showed Steven some of

Leslie's work. I said that there was a way to tell hour-long stories using this

technique if it's not abused, if there's some sort of a philosophical and visual

reason for it. If everything is motivated, and if it's guided by a principle of

energy -- whether it's an eye flick or a hand movement or burst of physical or

verbal energy, it all comes from somewhere. And Steven grudgingly allowed

it and I, with unabashed enthusiasm, did it. It really did affect a lot of things.

In your features -- and "Frequency" is a good example of that -- you use

a lot of your television techniques and show they can carry a two-hour

movie. There's the way you layer in information, for example, so that you get

an inkling of a theme or an incident from various sources before you get a big

dramatic scene about it.

That goes back to the storytelling techniques and methods that Michael and

Steven invented on "Hill Street Blues." Their notion was that "exposition"

was the bad word; anything that smells of "show and tell" was immediately

and viciously dispensed with. Instead we had bits of information, either

visual or auditory, added together to create a whole that was greater than

the sum of its parts. If you're really watching "Hill Street Blues" or "NYPD

Blue" or "L.A. Law," or hopefully the movies that I've made, you're never

getting it all in one piece -- you're getting hints, you're getting pieces of the

puzzle as it comes along, and all off a sudden it becomes clear.

And in "Frequency" it's a mind-bender -- a very difficult journey if you're not

paying attention. If you blink and get up and go to the bathroom, you can

miss a piece of information that really ties it all together. You get a little bit of

information off the AM radio at the beginning of the movie when the truck's going

over the bridge -- from that, you heard about the nurses being murdered,

New York Mets baseball, solar explosions, a number of things that all begin

to add up as you move through the movie. But whether it's that, or what's

on television or newspaper headlines or in dialogue -- it was all laid out

rather carefully at different places to add up to a whole. And I find that fun to

do, like a puzzle piece.

The filmmaking in "Frequency" is efficient; to my eye, you don't get as

baroque as the fires in, say, "Backdraft." Did that efficiency come from TV,

too?

Certainly in TV you are constricted severely by time and money; the upside is

you learn to prepare, you have no choice, you get it done for a certain

amount of time and money or you turn into a pumpkin. But the fact of the

matter is, as I was describing the cops on those TV shows, this is not a story

about a fireman, but about Frank Sullivan (Quaid), a man who happens to be

a fireman. I had to rein myself in not to make the fires major events and just

go bullshit with all the toys, all the bells and whistles, at my disposal. It was

not about, say, Frank fighting a fire in a tunnel, but about him getting out; it

was not about the fire in that big warehouse, but about him trying to get out

with that girl. So -- less is more. There's kind of an adage in stunt work that

would be well applied in any kind of film work, which is "get in late, get out

early." That way you don't see the ragged beginning or the sloppy ending of it

-- you only see the perfect stunt, and you shoot it with that in mind. And the

same applies to a dialogue scene or a story sequence.

You first read the script to "Frequency" in November '97; what accounted

for the strength of your response, and why did it take so long to

launch?

My dad had died a year and a half before I read it and that was still pretty

fresh in my mind. The notion of mixing wildly disparate genres and trying to

make it work -- that was something I wanted to try again, because I had

tried to do that in "Fallen" and it hadn't worked that well. I wanted to prove

to myself that I could get that to happen. The bells and whistles were fun,

the time travel was fun, but the heart of it was that relationship between

father and son -- these two men who at a freakish moment in time are able

to say something to each other that they would never say if they did not

understand fully the fragility of the moment.

The movie was considered by the studio to be high-risk because it was such

a combination of things -- they weren't sure how to sell it. It took a while to

get a budget that was even remotely real. I knew going in, as did my

producer, that this was an expensive proposition, and that we had no

business making it for the money or for the budget that we had. But we

were going to try.

The project had been adrift when I came aboard. It had a huge budget

under other directors -- under one director of note, almost twice the budget I

had. And they were not getting the cast to support that budget. I was

interested in all kinds of principals for the leading roles, but I discovered that

movie-star stars weren't interested in sharing the stage 50-50 -- and this

movie is a two-hander. Frank's no bigger a role than John Sullivan (Caviezel).

Some actors did not want to get close to the father-son stuff: It was too

painful for them, or they were not ready to go there. At one point, I had a

cast, but was not as happy with it as I had wanted to be, and one of them

bolted.

In the script, the father was 30, the son 36. One of the problems I was

having was finding 30-year-old male actors who had the kind of life

experience or emotional weight that would make the scenes work. I realized

I really needed a much more travel-weary, world-weary, experienced actor

and human being to play the father.

So casting Quaid must have been key.

I had been very fond of Dennis Quaid's work for years and when I saw him in

"The Parent Trap," I thought, this is a grown-up with a kid! You could see him

dealing with fatherhood pretty honestly. I also knew he had a 7- or

8-year-old son, and that his marriage was really solid and terribly important

to him. I said to myself, "There's the All-American guy." I also knew he would

look good in a fireman's outfit -- Dennis has got size. Put that coat and that

hat on Al Pacino and it would be a laugh. On Dennis it fits fine.

Shares