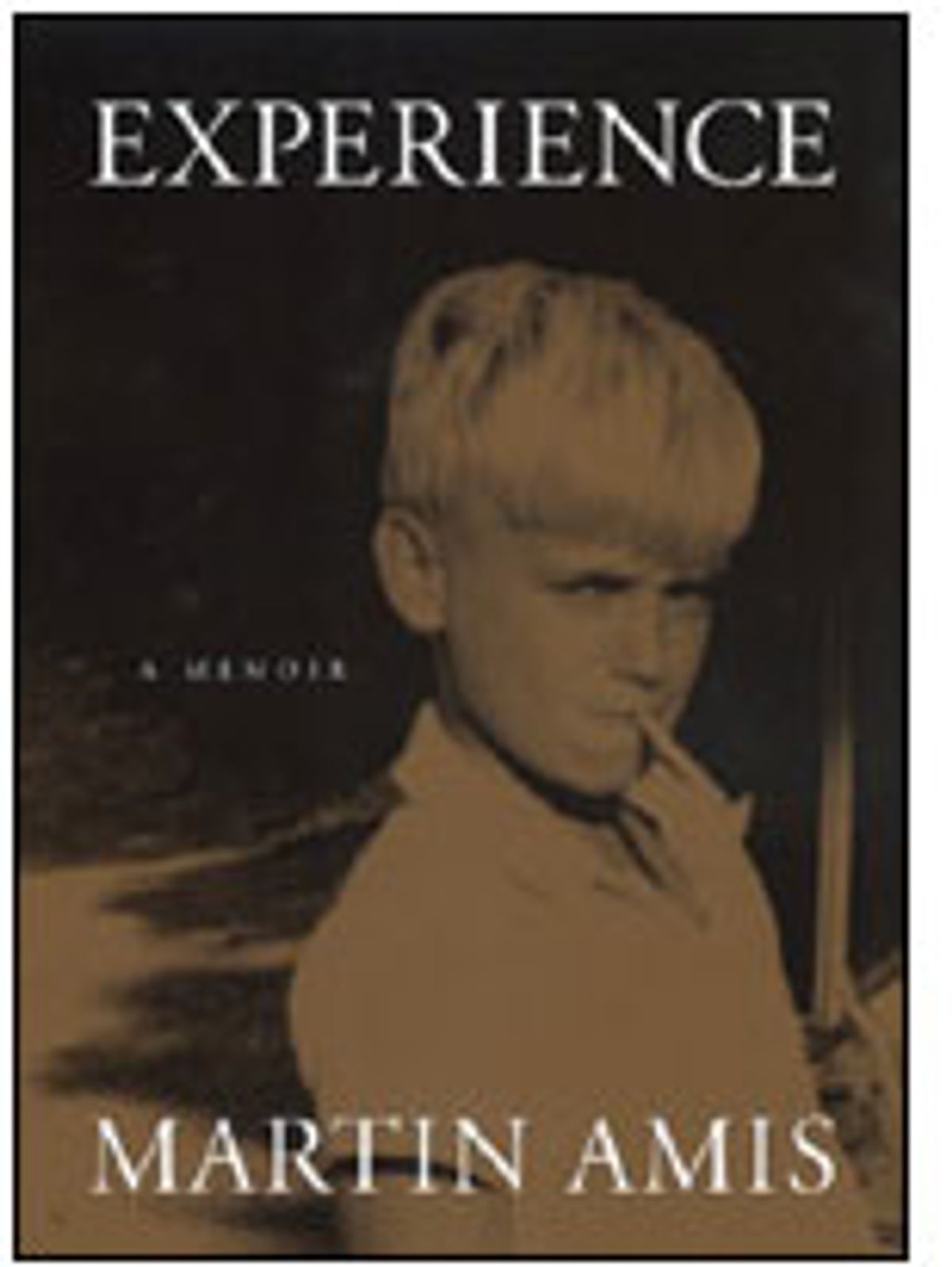

Martin Amis has been known as the bad boy of British letters for so long that it's easy to forget that last year he entered his sixth decade. At a pre-grandfatherly 51, he is that rare, endangered creature: a writer who makes headlines. And now the man who has been called "the best American writer England has ever produced" and "the Mick Jagger of literature" once again finds himself the subject of speculation and scrutiny: For the past month or so, the British press has been abuzz about the nearly simultaneous publication of "The Letters of Kingsley Amis" by Martin's famous father (author of "Lucky Jim" and the Booker Prize-winning "The Old Devils") and Martin's own much-anticipated memoir, "Experience."

Why the hubbub, the headlines of "Daddy Dearest"? Sir Kingsley's voluminous letters, written mostly to his close friend, poet Philip Larkin, touch upon several facets of his life (including intimate details of his first marriage, to Martin's mother), but what really cranked up interest was his unpaternal treatment of his novelist son. "Little shit," the elder Amis writes in reference to Martin's prodigious earnings for 1978. He disapproves of his son's postmodernist excesses and thinks him too heavily influenced by Vladimir Nabokov, who "fucked up a lot of fools here, including ... my little Martin." He also offers some jabs at Martin's politics: "Gone all lefty," he carps in 1986, after his son has declared his support for the anti-nuclear movement. "He's bright but a fucking fool."

Until now the son has remained relatively quiet on the subject of his father -- hence this latest wave of Martin mania. Hence, too, his desire to "speak, for once, without artifice," as he proclaims early on in "Experience" -- and not only about his father but about the tumble of events and imbroglios he was at the center of in the mid-'90s: his leaving his wife and children; his decision to part with his longtime agent, Pat Kavanagh, and the abrupt end of his friendship with Kavanagh's husband, novelist Julian Barnes; his huge advance for his novel "The Information" and the $30,000 portion of it he laid out on reportedly cosmetic dental work; and his discovery that his cousin, Lucy Partington, who disappeared in 1973, was a victim of Frederick West, Britain's most notorious serial killer. Finally, there was the death of his father in 1995. "The theme is clear," Amis says of the period: "partings, sunderings, severances."

In "Experience," he reflects upon all these dramas, but the book isn't the tabloid tell-all the British press seemed to be hoping for. Rather, it's a balanced, haunting work of memory and memorial, a surprisingly gentle meditation on fathers and sons, mortality, the loss of innocence, divorce, friendship, love -- what Amis calls "the main events," those "ordinary miracles and ordinary disasters" that shape you and define you and remain forever in your blood and being. No doubt critics will hail this intensely private evocation of a very public life as the arrival of a kinder Martin Amis. (We learn, for instance, that His Nastiness cries at the movies.) Still, there are passages in which Amis definitely seeks to set the record straight.

On his father's criticisms of him: "A fucking fool, in his lexicon, meant someone just about bright enough to know better." On his famous midlife crisis: "Like many people who have not yet turned forty, I used to give the Mid-Life Crisis little credit and no respect: it was the preserve of various dunces and weaklings." And, of course, the teeth: He devotes many pages to his lifelong dental woes, which, he insists, were far from merely cosmetic. He painstakingly describes the pain and trauma of dental surgery and of, as he puts it, losing his face -- he even casts his lot with his fellow literary tooth sufferers, Nabokov and Joyce -- but unfortunately he pleads his case too hard and returns to it too often.

Structurally, Amis spends two-thirds of the book jump-cutting between various eras and episodes of his life, from his adolescence to his relationship with Saul Bellow to a reunion with a teenage daughter he didn't know he had. But it's his father who haunts these pages most, and the last third of "Experience" focuses almost exclusively -- and touchingly, compellingly -- on his father, especially his last days. "I always knew I would have to commemorate him," Amis explains. "He was a writer and I am a writer; it feels like a duty to describe our case -- a literary curiosity which is also just another instance of father and son."

Quoting extensively, Martin demonstrates that he's a savvy and dedicated reader of Kingsley's writing. The reverse, however, could not be said: Kingsley stated publicly (on TV, in fact) that he "couldn't get on" with Martin's second novel, "Dead Babies," and he didn't even read "London Fields," which was dedicated to him and which many consider his son's greatest achievement. Yes, Martin dishes out the occasional dig -- at his father's anti-Semitism, at his misogyny, at his less successful writings -- but what finally emerges is a multidimensional, loving portrait of a man whom many regarded as the top comic novelist of his generation, yet who was afraid to be alone in his house after dark. Part fascinating literary memoir, part raw catharsis, "Experience" also represents a universal phenomenon: a son's attempt to understand his father and to make sense of his death.

Amis' nine novels and two short-story collections have been praised for their verbal virtuosity and their stylistic wonder, but criticized for their lack of soul and of humanity. "Experience" displays the familiar virtuosity and the wonderful style, but this time there's no faulting the humanity or the soul. Call it the full Martin.

Shares