"8 1/2 Women"

Written and directed by Peter Greenaway

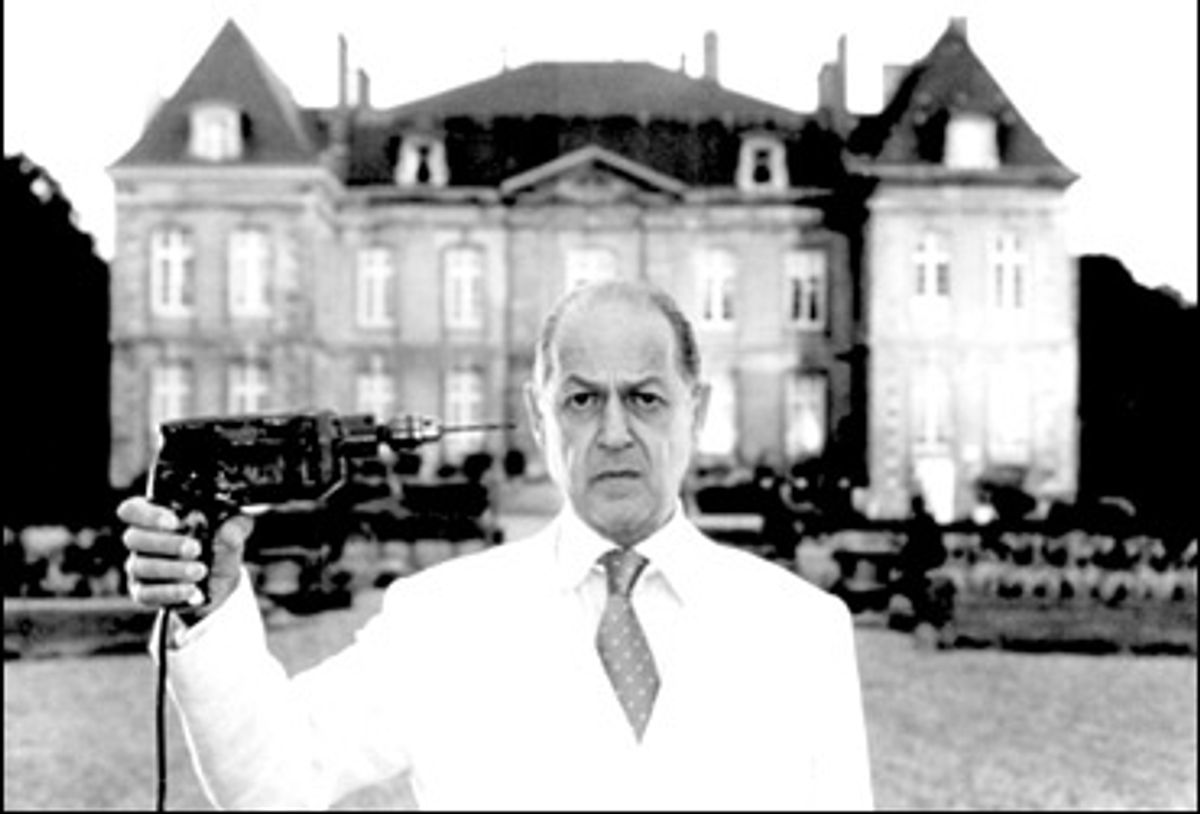

Starring John Standing, Matthew Delamere, Polly Walker, Amanda Plummer, Toni Collette and Vivian Wu

Toward the middle of Peter Greenaway's "8 1/2 Women," a young man named Storey Emmenthal (Matthew Delamere) insists on taking his recently widowed father, Philip (John Standing), to see Fellini's classic film "8 1/2." Storey hopes to distract Philip from his grief. As far as we can tell, father and son don't pay much attention to the movie; Philip wants to talk about the penis as an engineering achievement, to Storey's embarrassment. But when they get home, or perhaps on a later occasion when they're watching the film on video -- as usual in a Greenaway film, there's no consistent chronology of events -- Philip wants to talk about all the beautiful women in Fellini's universe. "How many film directors make films to satisfy their sexual fantasies?" he asks. "I should imagine most of them," says Storey.

Greenaway's fans might be tempted to view this as a kind of confession, a moment of rare candor and directness in the idiosyncratic English director's difficult and endlessly allusive movies. But while there's quite a bit of male and female nudity in "8-1/2 Women" (most of it quite beautiful perhaps because it so thoroughly defies conventional standards of beauty), the sex is mainly in the atmosphere rather than on the screen. The mood here is lovely, autumnal and sad, verging on tragedy if sometimes flavored with implausible farce. As Philip and Storey try to fill the void in their lives -- and their palatial Geneva estate -- with sensual adventure, the result may be Greenaway's masterpiece.

A veteran of the English stage, Standing is a wonderful blend of magnetism and pathos as Philip, a role of almost Lear-like emotional richness. When he regards his dead wife and howls, "Who is going to hold me and love me for my body as it is now?" all the artifice and architecture of Greenaway's filmmaking moves to the background. Motivated by loss, by Fellini's images and by the almost childlike greed that accompanies great wealth, Philip and Storey decide to fill their house with a harem of eight (or, finally, eight and a half -- and if you see the movie you'll have to figure that one out for yourself) personal concubines.

Their conquests range from the sublime to the ridiculous, and include a severe Japanese businesswoman named Kito (Vivian Wu), a would-be nun named Griselda (Toni Collette of "The Sixth Sense"),a skeletal horsewoman named Beryl (Amanda Plummer), whose principal lover is a pig named Hortense, and a perennially pregnant earth-mother type named Giaconda (Natacha Amal). The undisputed No. 1 among the eight and a half women is Palmira (Polly Walker of "Enchanted April" and "Emma"), a voluptuous schemer with whom Philip and Storey both fall hopelessly in love. You really can't blame them; Walker is heart-stoppingly beautiful, whether clothed or not, and Greenaway's shots of both her face and her body are positively rapturous.

Some viewers may find this movie sexist or misogynist simply based on its premise, but it's a mistake to take Greenaway's symbolic narratives too literally. Besides, all the women in the Emmenthals' house are there for good reasons: for money, for the dead wife's hats, to be trained as a Kabuki performer, to get pregnant and, in all cases but especially Palmira's, out of a sense of adventure. You could argue that Greenaway's view of gender roles conforms to a kind of reverse stereotype, in that the women are intensely practical-minded while Philip and Storey are hopeless dreamers. When the women grow tired of the game, they simply take control of their lives and move on, while the men are trapped in the seraglio of their own making, prisoners of their own inadequate emotional lives.

Out of what had seemed like the doldrums of his career and the isolation of being an art-film director left behind by history, Greenaway has made a masterful meditation on grief, a parable of sexual indulgence and power, a study of wealth and corruption. If "8 1/2 Women" isn't the best film of Greenaway's career, it ranks with anything this obsessive and utterly distinctive filmmaker has ever done. Furthermore, it's a hopeful sign for the 21st century that Greenaway can still make movies and actually get them distributed, let alone make movies as bracing and challenging as this one. Whatever you think of his work, the contemporary film world, which mostly assumes that the logic of mass marketing is the natural order of things, can only benefit from his peculiar presence.

Greenaway certainly isn't for everyone. Even in this film, one of his most emotional, he's a systematic and cerebral artist, driven by his obsession with games and numbers, water and birds, sex and death, along with a fascination with classic European works of art. You could almost say he isn't for anyone. Even his tiny audience of transatlantic elitists can't really keep up with his litany of sexual fetishes, technological flourishes and abstruse high-culture references; it's just that we're masochistic enough to sit back and enjoy the ride.

Since he emerged from the London avant-garde art scene with "The Draughtsman's Contract" in 1982, Greenaway has clung to the fringes of world cinema, not quite in the mainstream but never quite exiled to the art-school underground (if it still exists). His only flirtation with commercial success came in 1989 with "The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover" -- perhaps his darkest, cruelest and most opulent film -- and that was almost entirely accidental. A ratings brouhaha attracted viewers hoping for kinky sex; unprepared for the strangeness and density of Greenaway's work, they probably went home with the understandable impression that he was both a sadistic weirdo and an unsatisfying pornographer.

In the '90s, Greenaway seemed to retreat into a bloodless realm of pure aesthetics, as if in reaction to the post-Cold War decline of the European art-film tradition and Hollywood's global conquest. His only films to find U.S. distribution in the past decade, "Prospero's Books" (an overdecorated adaptation of "The Tempest," featuring John Gielgud in his last major role) and "The Pillow Book," with its humorless imitation of Japanese art, were extraordinarily beautiful but more than a little dull. In "8 1/2 Women," he not only conjures up the ghost of Fellini, the supreme sensualist of world cinema, but recalls his own more passionate works of the '80s, especially the marvelous if little-known "A Zed and Two Noughts."

Within the first few moments of "8 1/2 Women," we see a screen crammed with text, perhaps from the script, describing the opening montage, which we see almost at the same time: a series of spectacular exterior shots of neon-lighted Japanese pachinko parlors. Add some mysterious birdsong and an unknown cityscape, a lugubrious version of "Slow Boat to China" sung by Philip and Storey and a business meeting in which an enraged Japanese businessman punches Philip in the nose, bloodying the contract they are to sign. We are most certainly in Greenaway's territory, and if we have no idea where we're going, he seems supremely confident.

After their bereavement, it's strongly implied that Philip and Storey sleep with each other once and also enjoy a minage à trois with a Japanese girl before settling on their Fellini scheme. They're a little abashed afterward, but it's no big deal. ("You can do anything," Storey reassures his dad in bed. "Besides, you're my father and you're very, very, very unhappy.") They experience pachinko-parlor intrigue, several earthquakes (which Storey may be causing), sumo wrestling on TV, Kabuki theater and Verdi opera, a poisoning, a drowning and an extended argument about whether Jane Austen's heroines would be good in bed.

Greenaway has never really gotten credit for his sense of humor, which stretches from elaborate visual puns to crude slapstick (e.g., Hortense the pig), and "8 1/2 Women," his saddest and most heartfelt film, is also among his funniest. At moments in this magical, mysterious work the two come together, as when Philip seems to be asking his creator and the audience to turn away from his nakedness and emptiness. He doesn't like movies, he protests: "All of us compelled to share the same emotional experience. It's too intimate." Later, when considering Jean Renoir's dictum that every man has his reasons, he asks Storey hopelessly: "Do we have reasons? No, we just have lust."

Shares