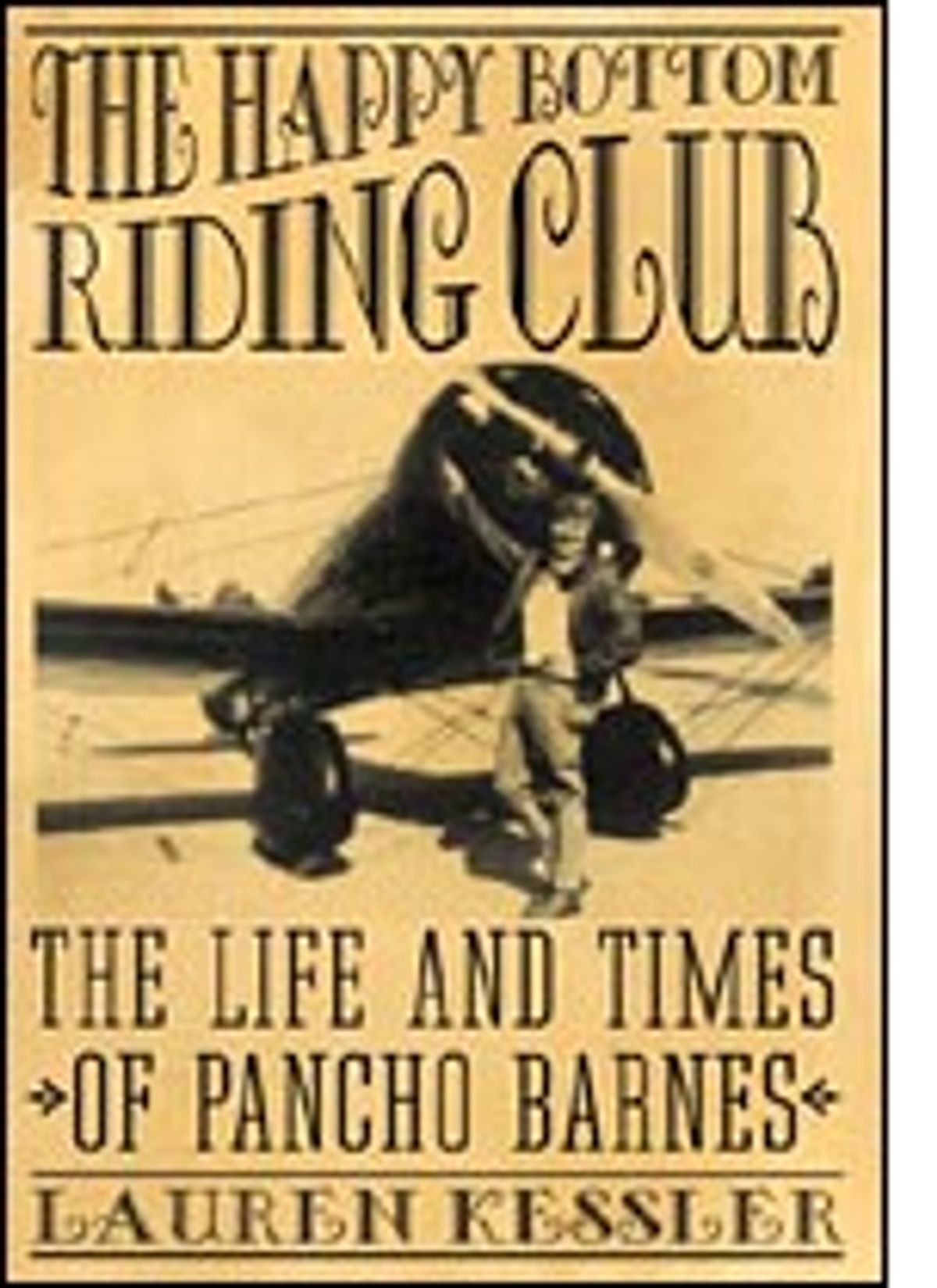

As the tough-talking, hard-drinking owner of the dive bar in the middle of the desert where test pilots like Chuck Yeager hung out, Pancho Barnes had a bit part in Tom Wolfe's "The Right Stuff." Now, she takes center stage in Lauren Kessler's "The Happy Bottom Riding Club," a remarkable book saddled with a silly name that evokes sex, horses and, perhaps, a minivan full of toddlers wearing softer, more absorbent Huggies.

Title titters aside, it turns out that Barnes, who died nearly a quarter-century ago, and packed at least a dozen eye-popping lives into her 70-plus years, more than holds her own as the subject of a biography. After just a few pages of her life story, it seems only fitting that the likes of Lassie, Amelia Earhart, Erich von Stroheim, Ronald Reagan and even Yeager, Mr. Right Stuff himself, are relegated to mere walk-ons. Pancho, aka Florence Lowe Barnes, was born to be a star.

In Barnes, worlds collided. Born to Gilded Age wealth and privilege, she became, among other things, a reluctant minister's wife and a heartlessly indifferent mother, an accomplished equestrian, an aviator who once set a speed record, a stunt pilot who toured in the Pancho Barnes Flying Mystery Circus of the Air, a Hollywood jack-of-all-trades and, finally, the owner of Pancho's Fly-Inn and the Happy Bottom Riding Club, the pilots oasis that may also have been a whorehouse.

Like a good novelist, Kessler has an eye for the quirky detail, and like a historian, she has a feel for the big picture, two talents that help her bring each of Barnes' interlocking worlds to life. Through Barnes' many jobs at the fringes of the movie industry (she started out renting her horses for cowboy movies, then became a stunt double and sometimes even a cameraperson and screenwriter), Kessler sketches Hollywood in its infancy, back when no-budget westerns were made on the fly and moviemaking was "still a seat of the pants operation where today's prop boy could be tomorrow's director."

Similarly, since Barnes learned to fly in the days when "navigating" might mean swooping down low enough to read road signs, Kessler vividly re-creates the heyday of early aviation, when female fliers, or "petticoat pilots," as they were sometimes called, raced each other all over the country in a series of wacky publicity stunts that made them media darlings, but often left them penniless.

Throughout her life, Barnes, who earned her nickname when she donned men's clothing and jumped a ship to Mexico, wanted just one thing: More.

She was, Kessler reports, the ugliest woman most men had ever laid eyes on (the author seems particularly fixated on her heroine's fleshy neck), with the foulest mouth they had ever heard. Yet for much of her life, Barnes had plenty of charm and plenty of money, a combination that won her four husbands and dozens of pretty-boy lovers whom she swapped as easily as she traded horses and airplanes.

Her opulent San Marino, Calif., mansion was an open house where guests drawn from Hollywood, the riding circuit and her pilot pals drank her liquor, traded stories till dawn and generally helped her run through several fortunes. Then, when Barnes moved out to the California desert, she enjoyed "playing Lady Bountiful among the desert rats." She summoned one old friend out to her ranch this way: "We will ride a pony, fly a kite and light cigarettes on one-hundred-dollar bills."

By the time she met Yeager and America's future astronauts, Barnes had already become something of a legend, but she was also beginning a slow, sad slide into self-parody. Many of the wild young pilots she caroused with were turning into buttoned-up military men, and those primitive runways scratched into the desert would eventually become Edwards Air Force Base and swallow up all she held dear.

Barnes' stomach-churning physical demise could give Stephen King pause. (Think hungry dogs and rotting flesh.) Yet Kessler refuses to make her heroine a victim of anything but her own excesses. Likewise, the author wisely resists the temptation to turn Barnes into a forgotten feminist icon -- something that might have been a stretch, anyway, considering that Barnes once commissioned a giant loaf of bread and stuffed it with two naked women. In the end, Barnes' epitaph might well be the quote that kicks off this engrossing, shamelessly entertaining book: "Ah, hell. We had more fun in a week than those weenies had in a lifetime."

Shares