With his lanky build, blond forelocks falling over his eyes, a white T-shirt, black jeans and a constantly ringing mobile phone, Srdja Popovic looks more like a rock star than the youngest member of the Belgrade city parliament.

At a press conference outside a slick glass independent media club in Belgrade last month, the 27-year-old student leader announced that his student group Otpor (Serbian for resistance) would officially register as a national resistance movement with the Yugoslav Ministry of Justice. It was a spirited announcement, and it was so crowded you could hardly get past the door to see the professors, actors, artists and members of Serbia's National Academy of Sciences and Arts who came to register as the first official members of the group. It should have been a celebratory occasion for Popovic.

Instead, he seemed tense and unhappy.

At a meeting only a few blocks away, the members of Serbia's 16 opposition parties were planning to retreat a step further from confrontation with Slobodan Milosevic over his recent crackdown on key Belgrade independent media organizations last month. The decision leaves Popovic, Otpor and the Serbian public more exposed to Milosevic's increasingly repressive dictatorship.

"We have a great problem with those opposition guys," Popovic said. "People are supporting us, and we have given the opposition part of our legitimacy. We are being attacked violently by the ruling party with all the mechanisms at the state's disposal. And we are losing so much energy on the opposition, trying to get them to understand the obvious: Milosevic is turning this place into a total dictatorship."

Facing the most forceful effort by Milosevic to clamp down on internal dissent since he came to power, Serbia's opposition parties have largely abandoned the Serbian population to cope with increasing pressure the government is mounting on them.

The opposition's failure to offer the population any constructive responses to the government's closure of independent media and Serbian universities, nor to its stepped-up beatings and arrests of student and pro-democracy activists, has led many Serbs to lose faith in the movement.

"This opposition is incompetent, corrupted, immoral and nationalistic," said Sonja Biserko, chair of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, in an interview. "This opposition has no moral energy. So the people wonder: If Draskovic doesn't care if the police closed Studio B, why should we go on the streets? In a way, the only truly dynamic actor on the Serbian political scene is Milosevic."

Biserko knows. Like the Otpor students, her group is facing growing harassment from the authorities. Last week, her office was raided by Serbia's notorious financial police. The move is the latest in a recent state campaign to demonize nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and human rights groups in Serbia as agents of the NATO governments that bombed Yugoslavia last year. Many believe the harassment is a prelude to an attempt to shut these groups down.

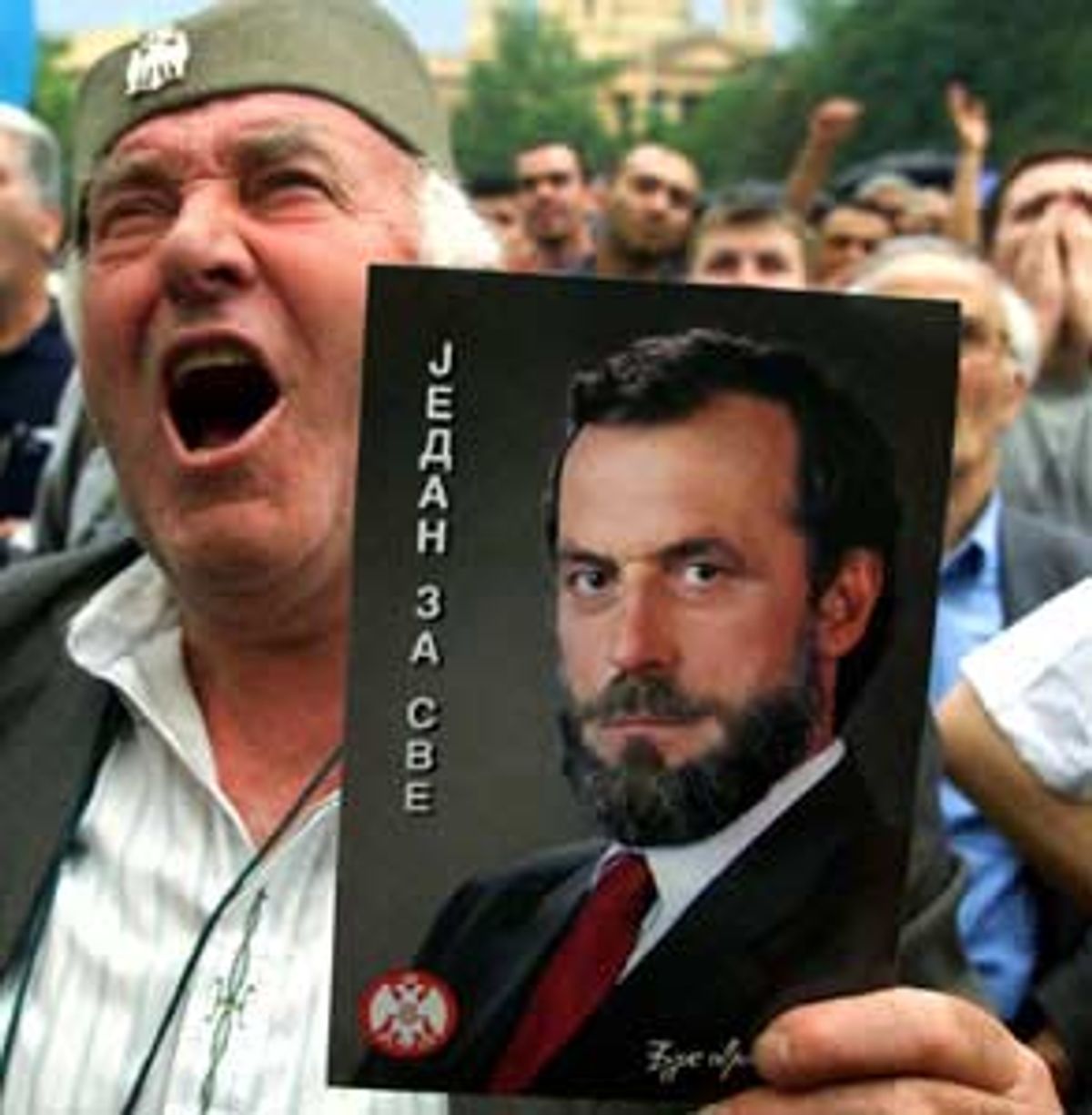

By the time it was canceled for lack of interest last week, a demonstration to protest the government's seizure of independent television station Studio B and other media drew only a few thousand protestors. One can hardly blame citizens for the low turnout, given the inexplicable absence of Vuk Draskovic, leader of the opposition party that controlled the station. The Serbian Renewal Movement (SPO) party leader failed to show up during the violent first nights of demonstrations, in which more 30,000 people protested and some 150 people were injured in clashes with police.

When Draskovic finally showed up three days into the tense demonstrations, he urged caution, telling protesters that defending the station wasn't worth risking a single life. His indifference was significant given that only two weeks earlier, at a rally in Ravna Gora, he told rowdy supporters who were shooting into the air to save their bullets because they might need them in the future.

Some of the harshest criticism of the opposition is coming from its own members, who say the sheer number of opposition parties means they are unable to reach consensus on meaningful steps to counter Milosevic's campaign of repression.

"The opposition has two problems. It's too big, 16 parties ... It's difficult to reach agreement on anything," said Zarko Korac, a psychology professor and leader of the liberal Social Democracy Party.

"The second problem is [that] big opposition leaders have been in power for years, and they are not willing to risk losing what they have," Korac continued, alluding to Draskovic's party's control of Belgrade and several other Serbian towns.

Mladomir Novakovic, mayor of the central Serbian city of Kraljevo and a member of Draskovic's SPO Party, also criticizes Belgrade opposition leaders for falling out of touch with the people.

"We here in Kraljevo are more common people, close to the land and the people," Novakovic said in an interview in his office last week. "The leaders up in Belgrade have risen higher and higher, they are more separated from the people, they think that if they sit in their salons and wave their hands, thousands of people will go into the streets."

Events in Moscow last week also suggested that the Serbian opposition movement may be losing its traction internationally. When Draskovic and fellow opposition pols Zoran Djindjic and Vojislav Kostunica sought Russia's support in finding a peaceful resolution to the current crisis, they were snubbed. The Serb democrats requested a meeting with Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov, but he instead shunted them off to a deputy.

It's not clear what kind of support the opposition leaders thought they could get from the Russians for free speech and democracy in Serbia. President Vladimir Putin has recently shown his own disregard for free speech in Moscow, where his government has been busy raiding independent media, harassing journalists it considers critical of his government. Putin recently hosted Milosevic's defense minister, General Dragoljub Ojdanic, who is under indictment by the U.N. war crimes tribunal, for a five-day visit, even inviting him onto the presidential podium during celebrations to mark the victory over the Nazis in World War II. The move so angered the Clinton administration that Secretary of State Madeleine Albright reproached Ivanov during a meeting of NATO foreign ministers in Florence, Italy, two weeks ago.

Close advisors say Draskovic is extremely depressed and afraid for his life. Last fall, Draskovic's brother-in-law and three close aides were killed in a suspicious car accident on the way back from a rally. Draskovic, who was also in the car, narrowly escaped death. He was even recently quoted in the local media saying he wishes he had died in the wreck.

A top advisor, Ognjen Pribicevic, says Draskovic and his wife Danica, who have no children, treated the aides like sons.

But fellow opposition politicians offer a less generous assessment for Draskovic's newfound passivity. They say the SPO leader may be restraining further protests because he has delusions that Milosevic will appoint him as his successor, a kind of Vladimir Putin to Milosevic's Boris Yeltsin. In addition, they point out that Draskovic's control of Belgrade is extremely lucrative, with or without Studio B.

"Draskovic dreams of being deputized as a Putin," professor Korac said. "But Milosevic tried to kill Draskovic. Milosevic would never give up political power, even without the Hague indictment. Everything is profoundly different."

Another opposition leader, a member of the pro-West Civic Alliance of Serbia (GSS), who asked not to be named, also points to Draskovic as the main obstacle to the opposition undertaking a campaign of civil disobedience to protest Milosevic's recent assault on the media.

"We had a choice. If we really wanted to intensify pressure on the regime, we should use the resources that are at the opposition's disposal," the Civic Alliance official explained in an interview, pointing out that Draskovic's party controls Belgrade's city hall and municipal services. "We could have, for instance, shut off the water and electricity to some buildings, stopped bus service all over the city. All we had to do was make the decision," to bring down normal life until free elections are called.

"But, if you think there is a danger in this kind of direct confrontation, then say that, and cancel these protests," the Civic Alliance official continued. "Say the situation is very complex, people are being beaten up, call off the rally. Instead, we have decided on no real activity. The rallies have died. We have achieved nothing."

Milosevic's greatest remaining threat may be student groups like Otpor that are now stepping in to fill the political vacuum left by the professional opposition politcians. They've been calling for strikes at their universities' faculties, and they were badly beaten by police last month outside two schools.

The Milosevic regime, fearful of a student uprising, even ordered the Ministry of Education to head off a massive student rally at Belgrade University by calling for all universities across Serbia to be closed for the summer a week ahead of schedule.

Students will even be banned from the libraries after that, and no make-up classes will be allowed. Meanwhile, a new law on terrorism being pushed through the Serbian parliament will provide the government with additional legal cover to charge and jail activists. The legislation seems targeted directly at Otpor, a group that has seen hundreds of its members arrested in the past few weeks. And the state-controlled media has launched a systematic campaign to portray the students as terrorists, fascists and foreign mercenaries for NATO.

The student movement has also criticized the opposition establishment. But Ognjen Pribicevic, a top advisor to Draskovic, denies Otpor's accusation that the opposition is retreating.

"We are satisfied with the statement of the Russian foreign ministry, that condemned the regime's use of violence, and said that television Studio B should be given back to the Belgrade city authorities," he said in an interview last week. He criticized the idea of a campaign of civil disobedience to protest the increasing repression.

"It is extremely stupid to cut off water and electricity and bus service. I don't think the citizens would support that," he said.

Milosevic, meanwhile, is making it harder for Draskovic and his SPO party to launch such a campaign. In a preemptive strike last week, Serbian authorities seized control of Belgrade's public bus service.

Nevertheless, Pribicevic, who took a degree from Oxford University and was once close to Milosevic's wife Mira Markovic when they both worked in the Communist Youth League at Belgrade University, admits that the opposition does not have a strong enough strategy for replacing the Milosevic regime.

"This is a very bad moment for the opposition. The most important thing is that the citizens of Serbia want to see the [defeat] of Milosevic, but they want it to happen peacefully, through elections. They are not prepared for a civil war. They are frightened of that."

The Civic Alliance official agrees. "Milosevic can be very satisfied. He took the media and showed the opposition has no idea what to do. Maybe the united opposition will become divided, and the Serbian people will increasingly turn against the opposition, and will not vote."

Shares