Bugs Bunny spins around. A table and a nail file materialize out of thin air, and Bugs mugs at a huge, orange creature who has been chasing the rabbit through a mad scientist’s lair. Instead of trying to escape from the creature — who wears sneakers — Bugs leans in with the nail file and starts to give him a manicure. “My, I’ll bet you monsters lead interesting lives,” he says in a high, effeminate voice. The monster is, of course, disarmed. The fast, unexpected and hilarious sequence belongs to the Warner Bros. cartoon “Hair-Raising Hare” (1946), one of the funniest of the hundreds of Bugs Bunny cartoons.

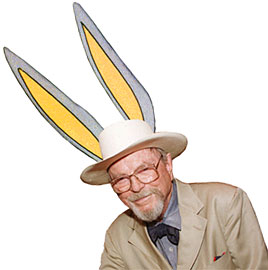

The man behind the cartoon was the celebrated Chuck Jones, the director of great WB animated shorts and the creator of the Road Runner, Wile E. Coyote, Pepe Le Pew and that now-ubiquitous singing amphibian, Michigan J. Frog. Though only one of several people who directed cartoons for WB in its 1940s and ’50s golden age, Jones has become so genial and likable a representative of Looney Tunes — in interviews and in two entertaining books of memoirs, “Chuck Amuck” and “Chuck Reducks” — that now he is routinely talked about as though he were the only representative of that great cartoon tradition. Jones, in fact, is the only WB cartoon director to receive a special Academy Award for his work (in 1997), and no cartoon director has more famous or influential fans: Steven Spielberg, for one, wrote the foreword for “Chuck Amuck.” There have also been laudatory essays on Jones by well-known film critics; Time’s Richard Schickel singled out “a genius named Chuck Jones” as the greatest figure in WB cartoon history.

But what hasn’t been mentioned by such critics is that Jones receives a disproportionate amount of the acclaim for WB’s finest moments. Jones had a golden decade at WB ending in the mid-’50s, but the rest of his career never lived up to that period. Further, his early cartoons were mostly mediocre Disney imitations, and other directors did far more than he to invent the style of WB cartoons. Finally, his accounts of WB cartoon history, especially about director Bob Clampett, have not always been strictly accurate. Chuck Jones undoubtedly created some of the finest cartoons ever made, but his spotty legacy deserves another look. Could the most celebrated director in cartoon history be as overinflated as an Acme balloon? It’s a funny business.

Jones’ career as a cartoon director started in 1939 with “The Night Watchman,” a short, sappy film about a terrified kitten put in charge of patrolling for mice. Jones spent the next three years making some of the dullest cartoons at the studio, full of cute little characters doing cute little things. At the time, WB cartoons were pulling ahead of the more sedate shorts of Disney and the less disciplined work of Max and Dave Fleischer. Tex Avery had created Bugs Bunny in “A Wild Hare”; Bob Clampett was making bizarre and brilliant cartoons like “Porky in Wackyland”; and Friz Freleng created the landmark animation/live-action combination “You Ought to Be in Pictures.” Jones’ main contribution to WB in this era was Sniffles, the wide-eyed, inexpressibly annoying little mouse whose warmhearted adventures ruined many a child’s Saturday morning (and who has recently returned in an MCI commercial to torment a whole new generation).

Even at their best, Jones’ early cartoons were low-budget Disney; at their worst, they could be as slow and ponderous as “Good Night Elmer” (1940), where Elmer Fudd spent an animated eternity trying to blow out a candle. Jerry Beck and Will Friedwald, in “Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies: A Complete Illustrated Guide to the Warner Bros. Cartoons,” call this “one of the most irritating cartoons ever made,” though it has competition from anything starring Jones’ other early creation, Conrad Cat.

In 1942 Jones pulled himself out of his rut — he “finally saw the light,” as Tex Avery recalled — and started to make consistently funny cartoons. His one-of-a-kind masterpiece “The Dover Boys” (1942) featured stylized character and background designs and an all-human cast that influenced the later cartoons of Columbia’s UPA studio (“Mr. Magoo”). Yet except for that one piece, Jones was not an innovator but a consumer of other people’s innovations. The faster pace, the violent gags, the topical references, the standard catchphrases — all of these elements had already been developed by Avery, Clampett and Freleng before Jones got around to using them.

In the late ’40s, and especially after forming a full-time partnership with gag man Michael Maltese, Jones hit his stride as a director. There was some indication in the early ’50s that his well would dry up — he retired some of his funniest characters, like the scheming mice Hubie and Bertie, to concentrate on the most formulaic characters (Pepe Le Pew, the Road Runner) — but on the whole, his cartoons earned all the praise they’ve received. The trouble is that the brilliant period didn’t last very long; a definite decline began in the mid-’50s. The turning point probably came in 1955, when the WB cartoon studio opened again after having been shut down for a few months. Though most of his old crew eventually came back, including Maltese, Jones’ work started a gradual but clear shift toward some form of what it had been when he started: slow, cute and not all that funny.

The changes in Jones’ style can be most clearly seen by looking at the changes in his treatment of WB’s biggest cartoon star. From 1943 to 1954 Jones made some of the best Bugs Bunny cartoons, including “Hare Tonic” (1945), “Rabbit of Seville” (1950) and “Bully for Bugs” (1953). Jones’ trick was to keep a two-dimensional character three-dimensional: In “Bully for Bugs,” for example, Bugs slapped a ferocious bull in the face, shouting: “Stop steamin’ up my tail! Whaddya tryin’ to do, wrinkle it?” It’s Bugs’ hotheaded emotional reaction that’s the key to the scene; he may be in a good mood when he pops out of his rabbit hole, but when someone tries to push him around, no matter how big and fearsome that someone is, he’s going to get angry.

Starting in 1955, most of the variety (and much of the appeal) was gone from Jones’ Bugs. Writing about Jones’ “To Hare Is Human” (1956) in his book “Hollywood Cartoons,” Michael Barrier comments that Bugs in this cartoon is “too pleased with himself,” and that’s true of Jones’ post-1955 Bugs in general. The new Bugs was no longer a brash wisecracker but a calm, reflective type who rarely got angry. He could, however, offer instead a gentle smile and a thoughtful comment on a situation that he didn’t take very seriously. (Jones plays a similar role in interviews.)

While Jones in his prime had usually been careful not to let Bugs heckle anyone without sufficient provocation (“Without such threats,” he wrote, “Bugs is far too capable a rabbit to evoke the necessary sympathy”), he would also let Bugs inflict a lot of hilarious, gleeful damage once provoked. In “Homeless Hare” (1950), Bugs politely asked a construction worker not to dig up his rabbit hole. When the worker refused, he got a not-so-polite telegram from Bugs (“OK, Hercules, you asked for it”), instantly followed by a perfectly timed steel beam to the head.

But after 1955, Jones doesn’t seem to let Bugs do anything, violent or not. In 1955’s “Knight-Mare Hare,” Bugs spends most of the film not acting but talking, making cute asides to the audience or making tired “nobility” jokes about jazz musicians (“Earl of Hines, Duke of Ellington, Count of Basie”). His only violent action is to stick out his foot and trip someone.

Or compare Jones’ “Hare-Way to the Stars,” (1948) with his “Hare-Way to the Stars” (1958). Both of them have the same basic story: Bugs was blasted into outer space, where he stopped Marvin the Martian from blowing up the Earth. The first cartoon allowed Bugs a wide variety of funny emotional reactions, like fear (“No, I don’t wanna go!” he whimpered while being taken to the spaceship, “I’m too young to fly!”) and shock (realizing that the Earth was in danger, he did a double-take and shouted, “WHOA!”). In the remake, Bugs walked around the stylized backgrounds with a bored smirk on his face; Marvin’s plans provoke nothing but another stylized pose.

Jones’ later WB cartoons also have a problem with character design. While the backgrounds of these cartoons (conceived by Jones’ favorite layout artist, Maurice Noble) look spectacular, the characters look all wrong. Jones never stopped loving huge eyes and exaggeratedly cute characters. The bane of his early cartoons resurfaced when he redesigned several WB characters to look wide-eyed and flabby.

Even the Road Runner series, which, as Barrier notes, was less affected than the others by the changes in Jones’ style (perhaps because a cartoon about the Coyote’s failures had to be bleak and violent, which prevented Jones from getting too sweet), was eventually weakened by these changes in design; the Coyote, once a classic combination of evil predator and pathetic screw-up, became so wide-eyed and cute by 1960 or so that he was only pathetic, constantly looking toward the audience for sympathy and losing the villainous edge to his character. It didn’t help that after Maltese left the studio in 1960, Jones started coming up with his own story material for the Road Runner cartoons, and his gags tended to be slow and drawn-out rather than the rapid-fire twists that Maltese wrote.

This tendency to slow down was another early problem that had already crept back into Jones’ cartoons by the late ’50s. All the WB cartoon directors were running out of ideas at the time, yet Jones’ cartoons seemed unusually obvious in their attempts to milk jokes for every ounce of comedy; there was so much pausing, eye-rolling and lip-quivering that every gag seemed to take twice as long as it should. In “Ali Baba Bunny” (1957) Jones had a character split a hair on Daffy Duck’s head with a sword. Jones started with a slow setup, then followed the split with a long pause, a Daffy whimper and another pause before the duck finally ran away. A joke that took about two seconds in most cartoons was needlessly stretched out, and the unpretentious wit and speed of the best WB cartoons was replaced by a tendency to dissect and analyze.

No post-1955 Jones cartoon is more analytical than “What’s Opera, Doc?” (1957), often named as the greatest cartoon ever made. I once attended a screening of old Warner Bros. cartoons that ended, as so many of these programs do, with “What’s Opera, Doc?” After the wild laughter and applause that had greeted most of the other cartoons shown that evening (including many by Jones), the audience reaction to Jones’ acclaimed Wagner spoof was surprisingly lukewarm, the laughter sporadic and the applause merely polite. As I was leaving the theater, I overheard a man: “But it’s not funny,” he said. And he was right.

“What’s Opera, Doc?” is sort of a masterpiece, and its combination of lowbrow and highbrow art forms makes it a pop-culture critic’s dream. But it’s also a one-joke cartoon: Bugs and Elmer are doing the same stuff they always do, but they’re singing it! Compare Freleng’s 1945 cartoon “Herr Meets Hare” (Bugs vs. Hermann Goering), which used the same Bugs-as-Brunhild routine, complete with oversized horse and Wagner’s “Tannhauser” on the soundtrack. This version is less strikingly designed and staged than Jones’, but it’s also funnier, reveling in the absurdity of Bugs’ drag routine and his adversary’s Siegfried costume. Jones, by contrast, almost seems to take the whole thing seriously. “What’s Opera Doc?” has been described as the apotheosis of Looney Tunedom, but in many ways it’s the antithesis of the Looney Tunes style: a big, lush, beautiful production where the audience is invited to sit up and marvel rather than laugh. Positively Disneyesque.

After the WB cartoon studio folded in 1963, Jones went to MGM. His time there is remembered for one Oscar-winning short, “The Dot and the Line,” and one successful TV special: “How the Grinch Stole Christmas,” where Jones’ preference for slow, formalized movement and wide-eyed facial expressions seemed to suit the character of the Grinch. But most of Jones’ other work at MGM has the faults of his late-period WB cartoons without the saving grace of the old WB characters; for example, his other Dr. Seuss adaptation, “Horton Hears a Who,” was slow and lumbering. Worst of all was the series of terribly unfunny Tom and Jerry cartoons that Jones was hired to direct in the ’60s.

Perhaps Jones’ most disappointing project from the MGM period was his 1971 TV special based on Walt Kelly’s great comic strip, “Pogo.” Kelly’s work, with its combination of satire and slapstick, seemed ideal for animation, and the Chuck Jones of 1950 might have been perfect for the project. The Chuck Jones of 1971 was another matter, and even though Kelly was credited with the script and some of the voice work, he was reportedly displeased with Jones’ finished product. Ward Kimball, a Disney animator and friend of Kelly (himself a former Disney staffer), recalled in an interview that his last meeting with Kelly was “after the Pogo half-hour TV show that Chuck Jones directed, which was a disaster … I asked him, ‘How did you ever OK Chuck’s Pogo story?’ He said, ‘I didn’t, for God’s sake! The son of a bitch changed it after our last meeting … He took all the sharpness out of it and put in that sweet, saccharine stuff that Chuck Jones always thinks is Disney, but isn’t.'”

Most of Jones’ work after leaving MGM has consisted of unsuccessful shorts and specials with the old WB characters. But as his work became even less successful, Jones emerged as a highly successful publicist for his own history, creating a lovable persona in interviews, giving insights and recounting many enjoyable anecdotes. Less enjoyable, perhaps, has been Jones’ attempt to spread misconceptions about Clampett, who became a director a year before Jones did. Clampett’s early cartoons, unlike Jones’, were assured and hilarious; cartoons like “Porky and Daffy” and “The Daffy Doc” helped to define their characters, and their unprecedented pacing almost certainly influenced older directors like Avery and Freleng. Before leaving the studio, Clampett would create Tweety, as well as directing some of WB’s best-loved cartoons (like Daffy Duck’s stint as “Duck Twacy” in “The Great Piggy Bank Robbery,” and the famous adaptation of Dr. Seuss’ “Horton Hatches the Egg”).

Clampett left the studio in 1946, after less than a decade of directing cartoons, but there’s no denying his importance to WB cartoons. But Jones has certainly tried, reportedly resenting what he saw as the tendency of Clampett, in his own way as skillful a self-promoter as Jones, to claim a role in the creation of just about every WB character. The most infamous attempt came in Jones’ 1979 compilation film “The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie” (which mixed great clips from Jones’ classic cartoons with tiresomely twee linking material in the later Jones manner). Near the beginning of the film, Bugs shows a portrait gallery of the directors who contributed the most to his creation. The gallery contains Avery, Freleng, Jones, Robert McKimson … but not Clampett. It was a startlingly ungenerous gesture; even worse, it was a falsification of animation history, an attempt to erase Clampett from the story of WB cartoons.

Jones hasn’t stopped trying to minimize Clampett’s contributions to the studio. In “Chuck Amuck” he doesn’t mention Clampett once; in “Chuck Reducks” he deigns to mention the name exactly once (“Clampett’s Bugs was funny”). And in a 1998 interview with Mania magazine, he said: “As far as I’m concerned the one who mattered the least was Bob Clampett,” adding, perhaps in response to the continued popularity of Clampett’s cartoons, “Honestly, I think Bob is right in line with today … Bob was the one who liked all that ‘Three Stooges’ stuff.”

Jones’ disinformation campaign certainly hasn’t reached the public, which continues to enjoy Clampett’s cartoons alongside the equally great work of Jones, Freleng and others; nor does it detract from the enjoyment of Jones’ best work. It does, however, suggest that Jones isn’t always lovable. And that like his work from the late 1950s on, he isn’t very funny, either.