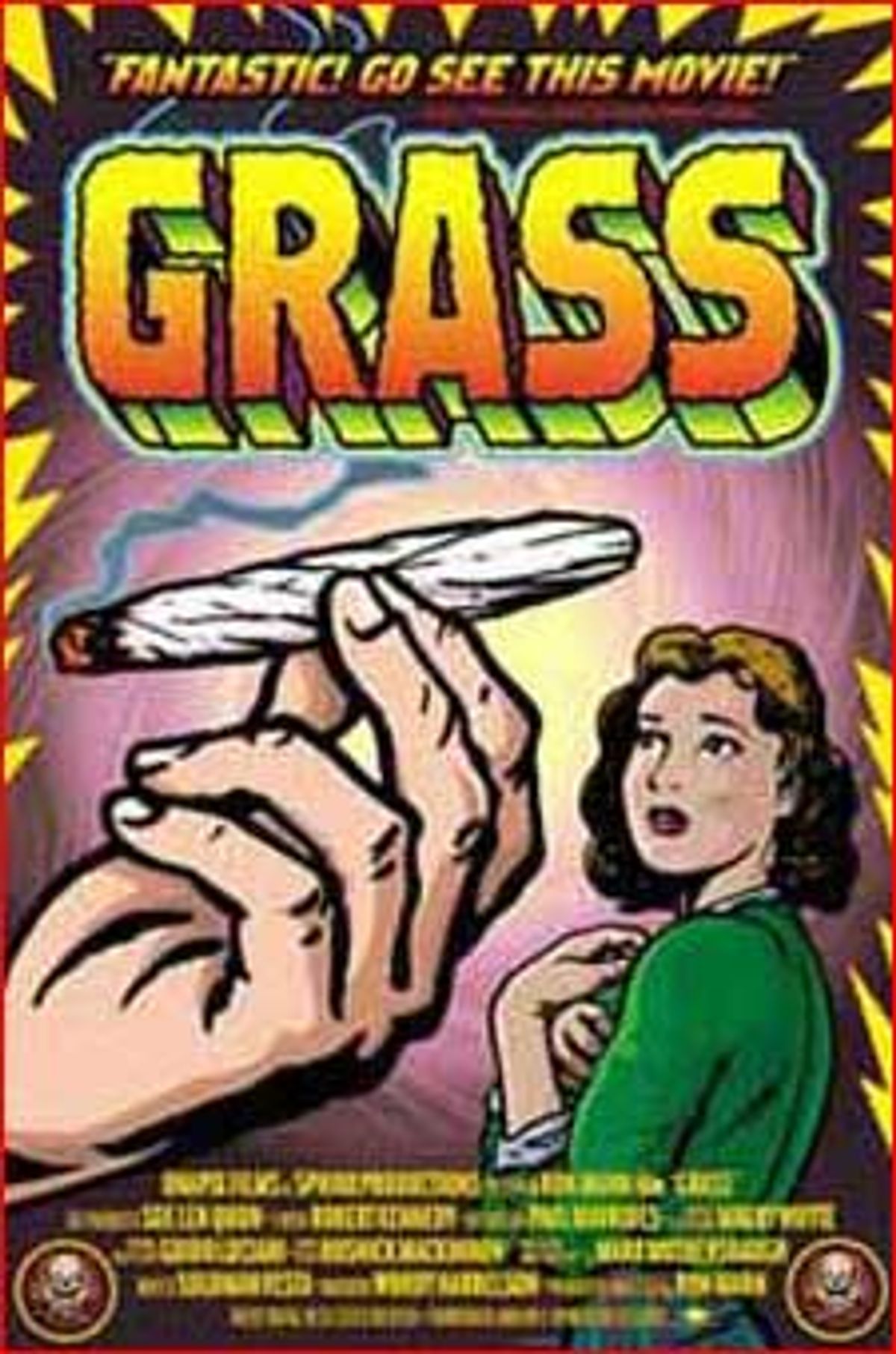

"Grass"

Directed by Ron Mann

Narrated by Woody Harrelson

The small triumph of Ron Mann's new documentary, "Grass," is that it reduces the massive, nearly 100-year attempt to wean the people of the United States off marijuana to one easily digested story line. In Mann's version, narrated by dope enthusiast Woody Harrelson, it's a tale with the plot turns and simple characterizations of a matinee melodrama: There's the crusading villain (drug czar Harry J. Anslinger), the wise hero (New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia) and the unlucky victims (imprisoned drug offenders). But there is no happy ending to this genial history of ganja in the 20th century. It finishes by tallying up the obscene multibillion-dollar cost of the drug war and the human cost of drug offenders locked up in local, state and federal jails and prisons. The figures would be laughable if they weren't so depressing.

The story starts with the Mexican immigrants and laborers who brought the recreational use of marijuana to the States in the early 1900s. They're quickly followed by the second significant strike against marijuana, the racist and xenophobic El Paso ordinance of 1914 (unmentioned is the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which required labeling of any cannabis contained in over-the-counter remedies), and clips of the earliest anti-dope movies, including a silent western in which a cowboy goes "bughouse loco" and shoots a man after smoking a brown-paper joint.

Mann, who also made the documentaries "Comic Book Confidential" and "Twist," wants to establish that the war on marijuana is a war of propaganda. One of the treasures of the film is a trove of celluloid brainwashing that depicts pot smokers as murderers, libertines and freaks who crawl around like dogs. (Most of the clips are anonymous, aside from the selections from "Reefer Madness.") If Mann were interested in a more accurate representation of what pot does, he'd have tossed in some tape of giggling teenagers, a couple of college students waxing philosophical about how weird cats can be and a middle-aged guy who can't remember the name of that, uh, you know. But "Grass" really isn't about the big picture. Instead, it's a finely crafted piece of counterpropaganda, sort of the ultimate visual aid to that perennial term paper arguing for drug decriminalization. If you need something a little more level-headed, go for the episode of "Frontline" that ran a few years back. But "Grass" is a lot more fun.

Mann blames much of the drug war on the efforts of one Harry J. Anslinger, commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics from 1930 to 1962, who pretty much saw only two sides to marijuana: "threat" and "menace." It was Anslinger's bureau that financed the early propaganda that said smokers would go insane, later suggested that they would become heroin addicts and finally made a connection between drugs and the communists in "Red China."

Mann breaks up the narrative arc with clever animated info-graphics designed by cartoonist Paul Mavrides and a short digression on Prohibition and Mayor La Guardia's crusade against an unenforceable law against alcohol that most of the populace didn't want enforced in the first place. Mann also offers a brief glimpse at the first medical study of marijuana conducted in the United States, commissioned by La Guardia in 1939 and finished in 1944. Like most of the subsequent studies concluding that marijuana was either safe, silly or even a fraction less than evil, it only angered the anti-drug warriors.

After some excellent use of sound design -- gurgling bongs, Merle Haggard singing "Okie From Muskogee" -- and a few more fab clips of famed dope smokers like Cab Calloway, Robert Mitchum and jazz drummer Gene Krupa, the film revs into the 1960s and 1970s, the golden age of grass. Despite the efforts of Elvis, Richard Nixon's deputized drug fighter, and Sonny Bono, who delivers a glassy-eyed warning against weed, the nation's youth -- and then the middle class -- increasingly turn on to the pleasures of smoke. Nixon's ramped-up anti-marijuana enterprise, which again contradicted the decriminalization suggested in 1972 by a committee he appointed to advise him on drug policy, kick-started the Drug Enforcement Agency and put more and more middle-class white kids in jail.

One of the more startling realizations the film makes is how close the United States actually came to legalizing grass. The work of activists in the early '70s -- as well as the reaction to all of those white kids facing 50 years in jail for selling less than an ounce of pot -- helped persuade first Oregon and then nine other states to decriminalize marijuana. Federal penalties for possession were reduced, mandatory sentences abolished. Even Jimmy Carter got on board the decriminalization train as a candidate and then president -- until one of his Cabinet members was busted for using drugs. In the wake of the scandal a proposal to decriminalize marijuana died in Congress.

Drug policy in the next two decades, of course, devolved into the Reagan era -- frying eggs, "Just Say No" and zero-tolerance laws. "Grass" sums up the new, official arguments against weed in the '80s and '90s: "If you smoke pot, you will be a loser," and "Bad things will happen, but we don't know what they are." They're as laughable, if not more so, than the connection to communism. George Bush promises that the prisons will make room for new offenders, and law enforcement under the Clinton administration carries out more drug arrests than under any other president.

"Grass" ends with a parting shot of an activist at a pot rally standing next to a statue of La Guardia. It's a sadly mixed message. Here are the hard figures: There are 2 million inmates in prison right now, and 60 percent are there for drug offenses. The FBI reported that there were 695,201 marijuana arrests in 1997. Of those, 87 percent were for simple possession, as opposed to dealing or distribution. There have been 11 million marijuana arrests since 1965. The rate is now at an all-time high. And all pot activists have is a good argument, a handful of numbers -- and one brassy cold politician on their side.

"Grass" is currently playing in Chicago, New York and San Francisco. It begins a 20-city run over the next month on Friday.

Shares