It's late on a muggy Saturday night in Hollywood, and guerrilla artist Shepard Fairey is hanging by his fingers from the ledge of an abandoned building. Moments earlier Fairey was pasting an 8-foot-high portrait of the late World Wrestling Federation star Andre the Giant on the building's wall, but things have suddenly taken a dramatic turn.

Fairey got about half of the colossal poster up before some rent-a-cops came a-callin'. In full Wu Tang-ninja "they'll never take me alive" mode, he hid from view, scrambling to the edge of the ledge while the private security guards radioed for backup.

Before the donut patrol surrounds the block, Fairey drops 12 feet to the concrete sidewalk below and hightails it across the street where other members of "the posse" wait.

"This kind of thing almost never happens," explains Fairey, 30, panting from the run. "It's very rare that I have any problems in L.A. -- especially this soon out."

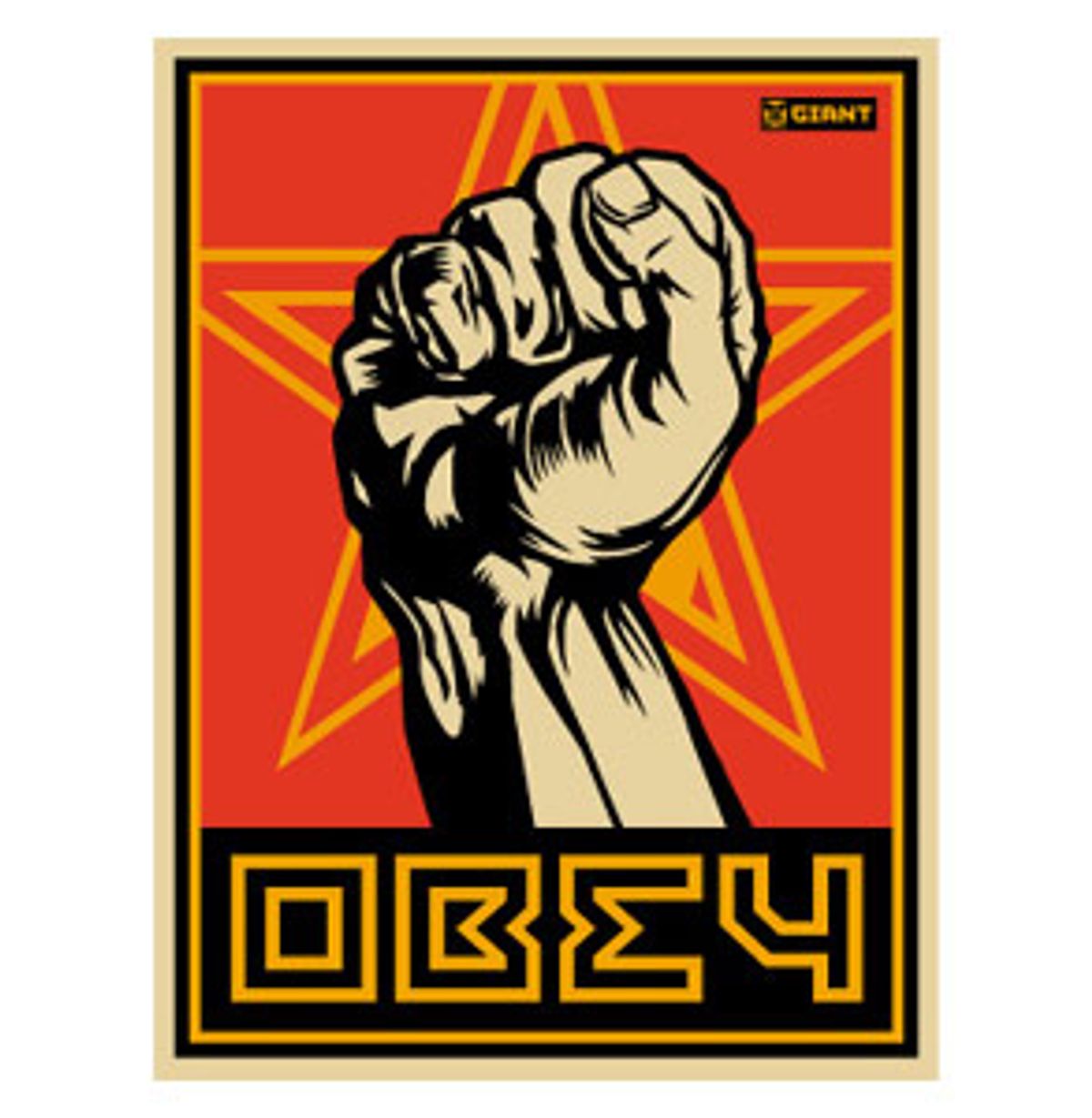

Fairey, who looks like a smaller, less menacing version of punk-rocker Henry Rollins, had just begun a weekend of "bombing" L.A. -- rolling with his crew and a carload of posters featuring the homely mug of monolithic wrestler Andre Roussimoff, who died in 1993, rendered in Fairey's totemic style and emblazoned with such Orwellian slogans as "Obey Giant," "You Are Under Surveillance" or simply "Obey."

It's a few minutes shy of midnight on a run that's supposed to flow until dawn. But already the posse's attracted heat. Fairey's had to temporarily abandon both his car, on a corner near the building, and a ladder and bucket of wheat paste up on the ledge.

"If they want to arrest me, they'll have to catch me," says Fairey of cops, rented or otherwise. "And I don't plan to let them catch me."

He can abandon the ladder, but he doesn't have that option with the car. If he leaves it, it might get impounded. But if he or any of his crew approach the vehicle, they risk being nabbed as the car is full of Giant paraphernalia. That's when Fairey's girlfriend, Amanda, a saucy brunette with more moxie than a '40s-era gun moll, grabs the keys and offers to give it a whirl. Knowing the value of a pretty face and trusting his girlfriend's gift of gab, Fairey lets her go.

Sure enough, about 20 minutes later, Fairey's gal speeds to the corner, tires screeching, where the posse's cooling its heels. When the security guys asked her about the Andre stickers stacked on the back seat, she told them it was for a local band. They grilled her a bit but didn't seem motivated enough to get the real cops involved.

The evening is saved, and Fairey's band of merry pranksters is off to paper L.A. red, white and black -- the dominant colors in most Giant posters.

Not to be outdone, before Fairey returns to his home base in San Diego the next morning, he and the posse double back to the abandoned building, finish the huge Andre head and retrieve the ladder. The bombing run has been a success. Though many of the scores of posters Fairey has put up will be removed in the coming week by city cleanup crews, he'll be back next Saturday to bomb L.A. anew.

Such run-ins with authorities are part of the game for the South Carolina-born Fairey, whose nearly 11-year-old Giant campaign is a worldwide phenomenon.

It all started when, as a student at the Rhode Island School of Design in the late '80s, Fairey -- on a lark -- designed a black-and-white sticker using the image of Andre the Giant and started putting it up all over Providence.

The stickers and posters, which boasted, "Andre the Giant Has a Posse," drew the ire of authorities as well as the adulation of the skate punks and other anti-authoritarian youth. Fairey made more stickers, sending them to friends nationwide and asking them to post them. Suddenly the Andre the Giant thing mushroomed into a movement far beyond what Fairey ever imagined.

"I realized that a lot of people didn't know what it was about," he explains later, during an interview at Black Market Design, the successful graphic arts firm he co-owns in San Diego. "But they liked it because they knew that the conservative people hated it. Initially, I wanted to elevate Andre out of the wrestling subculture to be on par with more mainstream cultural icons. That was the coup -- to raise Andre out of a subculture he should be embedded in."

"Even my very first print ad in 1992 was a picture of Elvis with 'Big' underneath and then a picture of Andre with the word 'Giant.' So it was saying that Andre is bigger than Elvis. I also did a shirt called 'The Famous Dead People Shirt,' which was a grid of nine people with Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, Jim Morrison, Bob Marley, Sid Vicious and Andre the last one in the corner."

Think of it as Phase 1 of the Giant campaign: the drive for icon-like status. In this phase, Fairey got people to like Andre by associating him, often humorously, with other adored pop-culture figures: Andre as Gene Simmons, Andre as Jimi Hendrix and so on. But it was a limited gag. So, around 1996 Fairey moved into Phase 2, borrowing heavily from communist propaganda, Russian constructivism and old-fashioned Madison Avenue hucksterism to blow Andre up into an Orwellian Big Brother figure -- ironically appropriating the most powerful aspects of each of these schools for his own anti-authoritarian campaign.

Fairey streamlined Andre's features and began to use the new Big Brother face in provocative ways. One image shows a police officer holding up a photo of "Big Brother Andre," with the slogan "Always Remember to Obey Law Enforcement Officials, Giant." Another shows a paranoid-looking man, who bears some resemblance to Orwell himself. Above his forehead is a series of Andre stencils in orange and black. To the right is the question "Am I under surveillance?" And below, in large block letters, is rendered "7'4" 520LB GIANT OBEY," the measurements being a reference to the deceased Andre's proportions.

"The people who most hate the 'fascist' stuff are the people who are most fascist," says Fairey. "It really pisses them off, and that makes the kids like it even more."

Fairey points out that when Andre (now referred to almost exclusively as "the Giant" to avoid any legal contretemps with the WWF) orders viewers to "Obey," he is in fact telling them to "Disobey." It's a message teenagers and young adults enjoy to such a degree that Fairey can barely keep up with demand for his posters, and he's had to farm out T-shirts and additional Giant merchandise to selected companies.

But that rebellious message would mean little without Fairey's street cred. From the beginning, Fairey adopted the tactics of graffiti artists and earned his stripes by "getting up" all over the nation. His willingness to put his ass on the line and be arrested hasn't hurt either.

Fairey's been busted in Philadelphia, Long Beach, Calif., and New York, where Mayor Rudolph Giuliani's anti-graff squads caught the artist with a ton of Giant stuff in '96. When Fairey, who's diabetic but in wiry good health otherwise, got sick in the slammer waiting for his court date, the authorities hurried his case through. He got off with time served.

Denizens of the street were impressed, and remain so. Stephen Powers, renegade author of "The Art of Getting Over," a book regarded as the graffiti bible, gives Fairey mad props. "I remember being on the fence about whether or not I liked his work," Powers e-mails from New York. "When a Bronx youth pointed to a face he did and said, 'Yo, I hear that nigga got one of those on the Great Wall of China!' That, and his extensive arrest record tell me he's really committed -- or should be committed."

"Who said, 'The tree of liberty must be watered with rebellion'?" Powers asks. "Shep makes questioning the BS we're handed on a daily basis standard procedure. That's necessary to our growth as humans."

Similarly, art commentator Carlo McCormick, a senior editor at Paper magazine in New York, is a fan of Giant art, demonstrating Fairey's ability to win over the intelligentsia.

"He's kind of advertising, but he's advertising 'nothing,'" says McCormick. "He puts it out in such a way that you need to fill in some sort of explanation. It's telling you to buy and obey, but you don't know what to buy or who to obey. It works on a very simple level of grabbing people and making them question what that sign is. Once you start to question what that sign is, maybe you start to question what they all are."

"He's really tapped into something. People, without even understanding phenomenology, get in on this elaborate joke of putting out this empty signifier."

Not everyone finds Fairey's work so engaging. Recently, he came to an agreement with authorities on his home turf of San Diego to cease his postering campaign there. Then there are adherents of the famous "broken windows" theory, which posits that crime is often the result of the breakdown in law and order as represented by such activities as vandalism, graffiti and the like. To them, Fairey is simply a lawbreaker who should be imprisoned and fined for his activities. For McCormick, the issue is not so cut and dried.

"Basically you have a lot of kids right now, at least I can speak for New York, who have seen the entire available visual surface of the city being turned into one big For Sale sign," McCormick says. "People are feeling, I don't know, violated. Our world is now cluttered with ads. There's no escaping them as you walk down the street. Maybe graffiti is at a wane right now in pop culture, but it's bigger than ever on the streets. There're more kids out there feeling obliged to take back that space for personal use."

Hence the appeal to teens and young adults who mimic Fairey's graffiti-art tactics by putting up posters and stickers on their own. Sure, they may not be able to quote Heidegger, but it doesn't take a degree in philosophy to understand that the whole Giant thing is fucking with the man.

Though Fairey gets up a lot on his own initiative, the help of the auxiliary members of the posse allows him to boast the distribution of over 1 million stickers worldwide along with more than 8,000 posters and thousands of spray-paint stencils.

(Fairey is quick to point out that he does not endorse vandalizing private homes or businesses, preferring abandoned property, construction site "snipe" walls or, his favorite, city-owned utility boxes. However, he has "liberated" billboards in the past on the grounds that everyone has a right to the visual space they occupy.)

Frequent road trips cross-country and abroad attest to the Giant campaign's subversive appeal. Last November, he was a smash in London when the hip Chamber of Pop Culture there sponsored a Giant blitzkrieg. Fairey similarly was hailed as a conquering hero in Japan in May when he bombed Tokyo to promote shows at the funky P House and Alleged galleries, who feted Fairey & Co. like they were the frickin' Beatles.

Where's the saturation point -- the plateau at which the colossal joke is over and the Giant campaign is no longer subversive? Fairey doesn't have an answer to that. For the time being, while his design firm caters to large corporate clients such as Mountain Dew and NBC, Giant remains his pet art project octopus with a ravenous appetite, one to which Fairey dedicates all of his excess time and resources. Will there ever be a time when he's no longer postering or bombing?

"Only if I'm wanted on a national level," he laughs, an eyebrow raised as if to say that all things are possible. "Until then, this is what I do for fun."

Shares