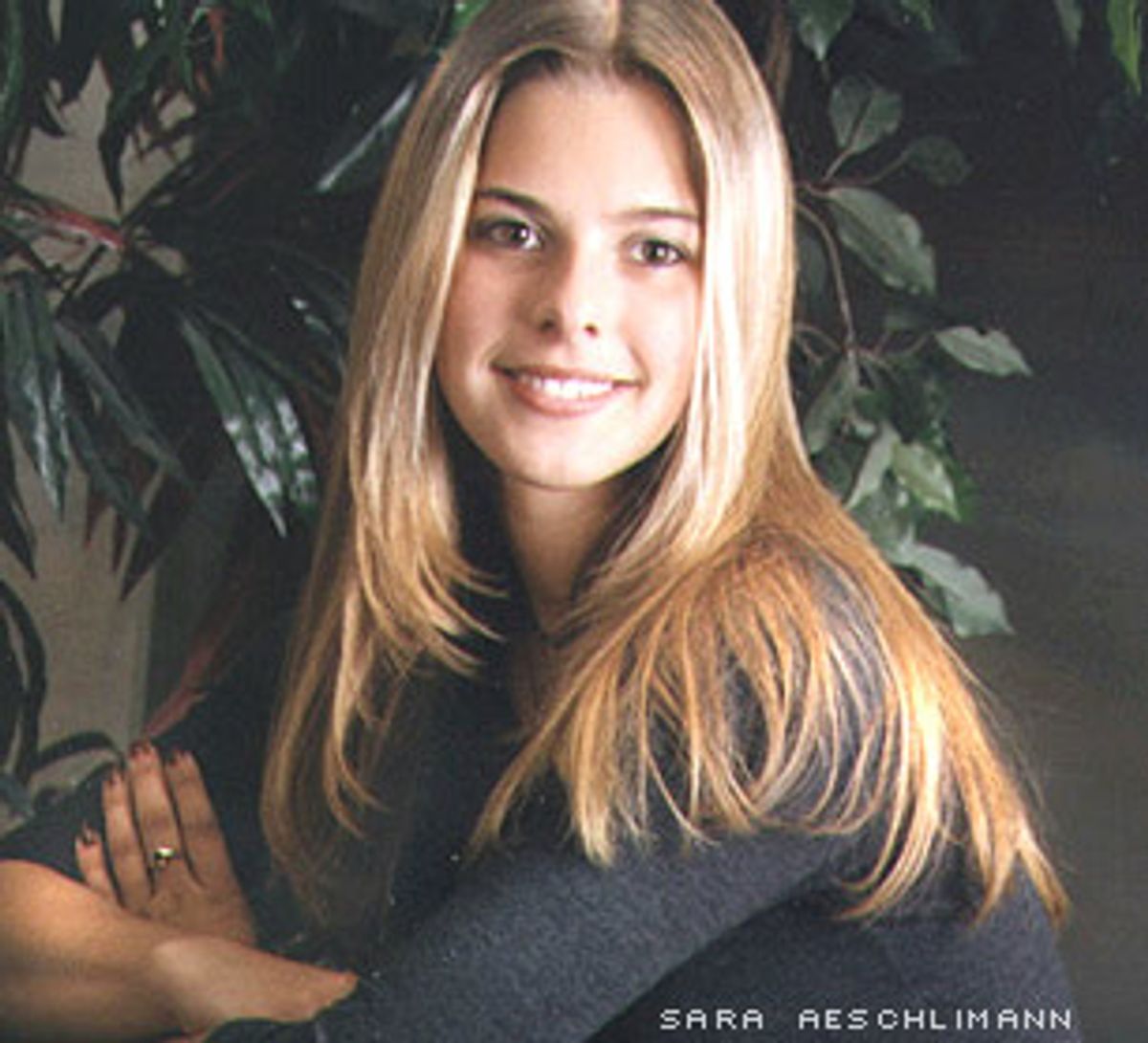

Sara Aeschlimann called her mom, Janice, in typical fashion at 12:30 one Saturday night. "I just wanted to let you know that I'm OK and that I'll be staying at Garrett's house," she said. Though Garrett Harth was three years older than 18-year-old Sara, they had known each other a long time, and he lived with his parents only five minutes away in the Chicago suburb of Naperville, Ill.

Like other teens, Sara had experimented with drugs, and had recently confided to her mom that she liked to smoke pot every once in a while. That worried her mother. But Sara had a job and a wide circle of friends, and was just a few weeks from high school graduation. All in all, she seemed OK. Aeschlimann thanked her daughter for calling and hung up.

A short time after the call, as Sara was watching TV and playing pool in Harth's basement, he reportedly offered the striking blond, brown-eyed girl a potent brand of ecstasy known as "double stack white Mitsubishi." She had apparently taken ecstasy for the first time a couple of months earlier, and the round white pills were supposed to be the hottest version of ecstasy around. She washed down a few and waited for the drug's effects to kick in.

Indeed, they did. Within hours, she was in convulsions and had to be rushed to the hospital. There, she lapsed into a coma and her body temperature rose quickly, not stopping until it reached 108 degrees. "She was bleeding everywhere," says her mother. "Her blood cells were just erupting. Her intestines were bleeding; her stomach was bleeding. She was bleeding from the mouth. She bit her lip when she had a seizure, and it wouldn't stop bleeding, but she was not moving at all."

By 3 the next afternoon, Mother's Day, she was dead. Instead of taking methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), the only chemical contained in unadulterated ecstasy, she had unknowingly swallowed paramethoxymethamphetamine, a much more dangerous chemical known as PMA. The DuPage County coroner's office determined that Sara died from an accidental overdose of PMA, a substance also believed to be responsible for at least two other recent deaths in the Chicago area.

Contaminated illegal drugs have never been a big issue in the United States. But if the demand for ecstasy continues to rise, as some researchers speculate it will, more and more dealers may start substituting deadly substances like PMA for less harmful drugs like MDMA.

"The ingredients for MDMA are highly controlled, and you have any number of people willing to make substitutes that are much more dangerous," says Dr. David Nichols, professor of medicinal chemistry and molecular pharmacology at Purdue University and one of the few to ever study the effects of PMA. "If you make one drug illegal, it will be replaced by a more dangerous drug. No matter how much you try to control it, people will come up with substitutes."

With the skyrocketing demand for ecstasy and its low production outlay -- it costs only 10 to 50 cents to make a pill that sells on the street for $20 to $45 -- there is a compelling economic incentive to sell the drug even if it's entirely made of another substance. "The rave scene is a huge market of people willing to pay $20 or $30 per pill to get high, and a lot of people are taking advantage of it," Nichols says.

The tablets and capsules sold as ecstasy might contain any number of adulterants. A quick look at the pill-testing results of DanceSafe, a harm reduction organization that analyzes such pills in a forensic laboratory, shows a cookbook's worth of ingredients that the drug is often cut with or downright replaced by: caffeine, DXM (dextromethorphan, an ingredient in cough suppressants), the psychedelic PCP, Valium and ketamine (an anesthetic). Ingestion of DXM, for example, has led to hospitalizion of ravers in cities like Oakland, Calif., and London. Included on DanceSafe's list of tested pills is a picture of white Mitsubishi, the variety of ecstasy that killed Sara.

But the problem of drug contamination and substance swapping by drug dealers is not widely recognized. An epidemiologist who attended a recent drug trends seminar in Washington, but who wishes to remain anonymous, says that a Drug Enforcement Administration representative at the conference commented that ecstasy is "a pretty pure drug." And a slide show presented at the seminar revealed that the DEA had analyzed more than 3 million ecstasy pills in 1999 and found that "all tablets contained some MDMA."

The Customs Service uses dogs to detect ecstasy being smuggled into the United States, but the canines can only detect MDMA, not adulterants. During the first four months of this year alone, around 5 million ecstasy pills were seized by customs, and in all probability the confiscated pills had some level of purity to them. The result is that the better-quality drugs are being taken off the market, increasing the ratio of contaminated pills to clean ones.

While there have always been risks involved in taking any illegal drugs -- which are produced with no oversight by any agency monitoring safety concerns -- drug contamination has traditionally been limited to substances like heroin.

R. Terry Furst, an associate professor of anthropology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, has studied the demographics of drug users. He believes the ecstasy-taking crowd, whose numbers have increased by more than 50 percent among high school seniors in the past two years, is a whole different demographic group than users of drugs like heroin, who are mostly from lower economic strata. Furst notes that "income is higher for ecstasy users because you have to be able to afford to go to a club, and you have to pay for the ecstasy, too."

Users of ecstasy are generally associated more with ravers -- who are likely to be found bunny-hopping on the dance floor while sucking on pacifiers -- than with the traditional type of drug users who will do anything for a fix. In other words, many of these users aren't aware of the inherent dangers of taking street drugs -- especially since ecstasy isn't often linked to fatal overdoses and its dangers are still being debated among scientists.

"After Sara died," says her mother, "her friends came to see me. They talk about taking drugs as if they were taking milk and cookies."

The adulterant PMA is not known to be useful for much of anything. Like MDMA, PMA raises body temperature, but much more severely. Unlike MDMA, PMA is not known to have very pleasant effects. Chemist Alexander Shulgin, known for his outspokenness on the positive effects of MDMA, synthesized PMA and tested it on himself several years ago. In an e-mail interview, Shulgin says he tried it half a dozen times and found that "it was not too enjoyable." He said that the chemical "compound is about twice as potent as MDMA."

According to representatives of the DEA's Chicago office, the PMA contamination found there was not a novice chemist's mistake -- it was deliberate. The process required to synthesize PMA is similar to the process of making MDMA, but the chemical precursors are totally different. As Mike Hillebran, a DEA spokesman says, it's "like making angel food cake and coming up with chocolate chip cookies."

The recent overdoses in the Chicago area are the first known instances of PMA in the illicit-drug market in the United States. However, it has shown up before. Between 1995 and 1996, at least six Australians were killed after ingesting PMA they thought was ecstasy, prompting scientists in that country to warn, in the American Journal of Forensic Medical Pathology, that "PMA has been associated with a much higher rate of lethal complications than other designer drugs, and that no guarantee can be made that tablets sold as Ecstasy are not PMA."

The known incidence of contaminated or substituted drugs in the United States is relatively small. One of the more publicized cases occurred in the 1970s, when the U.S. government, under President Jimmy Carter, supported a Mexican program of spraying crops with the pesticide paraquat in an attempt to stem the flow of opium and marijuana from Mexico to the U.S. Keith Stroup, then president of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, was so infuriated that then-drug czar Peter Bourne had tolerated the spraying, which many believed could be harmful to pot smokers, that he leaked a report that Bourne had snorted some coke at a NORML party. Bourne was subsequently forced to resign.

And in the early '80s, several people showed up at a neurology clinic in California, exhibiting signs of Parkinson's disease. It turned out they had tried a form of synthetic heroin called MTPT, which caused damage to the nervous system in much the same way Parkinson's does.

Drug overdoses are always hard to treat -- doctors don't know how much of the substance the user took, over how long a period it was taken, if there was any interaction with another drug already ingested -- but physicians say the problem skyrockets when someone comes in after having ingested a drug of unknown origin. In Sara's case lab technicians were unable to identify what she took until after she died.

"We don't have tests for most of these drugs," says Dr. Alan Kaplan, head of emergency services at Edward Hospital in McHenry, Ill., where Sara was taken. "We have to treat symptoms ... We would treat someone with hyperthermia caused by a [PMA] overdose the same way we would treat a roofer with hyperthermia. But these drugs," he adds, referring to so-called club drugs like PMA, "reset the body's thermostat so that it's very hard to control. Sometimes we just can't get ahead of it."

Six weeks after their only child's death, Sara's parents remain dazed. Robert, Sara's father, has been "fixing things around the house that don't need to be fixed," says Janice, who just returned to work as a receptionist at an animal hospital, and the days without Sara "seem very empty and long."

When she's not having nightmares of Sara's vacant eyes and her bleeding body lying on a hospital bed, what Janice Aeschlimann remembers is a daughter who "liked long walks in the woods" and had a pet parakeet who followed her around the house. "It's very hard to not see her in my mind," she says. "She is what I was. Now, I'm not that anymore. It's hard to be, and not be empty."

Sitting by Sara's bedside at the hospital, the Aeschlimanns told their daughter they loved her, and Janice vowed that her death would not be for nothing. "We just hope she heard us," she says. "We hope that she knows we were there."

Shares