The discovery of Raynard Johnson’s body hanging from a pecan tree in the front yard of his Kokomo, Miss., home last month stirred fears among many blacks that lynch law had again reared its ugly head.

Johnson’s family openly disputed the coroner’s ruling that their 17-year-old son was a suicide. They said he was murdered for dating a white girl.

Underlying their bitter charge was the recognition that Johnson, an African-American, had presumably violated America’s oldest and most enduring taboo: black males having sexual relations with white females. And while civil rights leaders quickly joined the clamor over his death, lost in the shouting is the fact that relationships between black men and white women have become increasingly controversial in black circles, too.

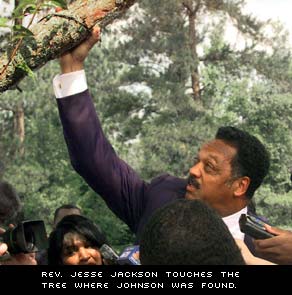

The Rev. Jesse Jackson insists Johnson’s death has the earmarks of a lynching. The NAACP hired a private investigator, and the Southern Poverty Law Center noted that the Klan had long used white fears of black men raping white women to terrorize blacks.

There is no tangible evidence that Johnson’s death was anything other than a suicide.

Indeed, many found the idea that he had been lynched for dating a white girl absurd. They point to a sevenfold increase in black and white marriages since 1960 — there are now an estimated 1.5 million interracially married couples. But these account for only a tiny fraction of total marriages, and the overwhelming majority live in multiracial urban areas.

Older blacks still have vivid memories of the lynch murders of 14-year-old Emmett Till for allegedly whistling at a white woman in 1955 and Mack Charles Parker for the alleged rape of a white woman in 1959. As late as the mid-1950s, interracial marriage was a felony offense in 30 states, with heavy fines and prison terms. Six years after the Supreme Court struck down school segregation in 1954, 29 states still outlawed black-white marriages. Maryland and Nevada went further, banning all sexual contact between blacks and whites.

The civil rights movement and the political emergence of Asian and African nations, however, made anti-miscegenation laws a political liability and the Supreme Court in 1967 finally dumped them. This did not sound the death knell for the taboo. Though legally unenforceable, bans on interracial marriages remained on the books in 12 states in 1979.

This week a New York Times poll offered new insight into black and white attitudes toward the taboo. Almost two-thirds of whites, and four-fifths of blacks, said they approved of interracial marriage. But the figure for whites jumped by 50 percent, while the black number edged up more slowly, from 70 to 79 percent.

In 1996, an informal survey in Ebony magazine found 40 percent of black women and 25 percent of black men saying they would not date a person of another race.

Hollywood and the TV industry are still unenlightened. They avoid showing black men and white women in intimate relations, mainly for fear of offending mostly white audiences and sponsors. But again, some black stars are reluctant to play romantic roles opposite white women — the most recent example being Eriq LaSalle, Dr. Peter Benton in NBC’s “ER,” who asked writers to terminate his relationship with a white doctor because his character had never had a successful relationship with a black woman. (This past season, Benton’s girlfriend was black.)

Just last week “Sex and the City” showed a hot liaison between Samantha and a black boyfriend, but it ended when the boyfriend’s black sister made clear she wouldn’t stand for his dating a white women.

Anti-miscegenation laws may be buried, and Americans may be more tolerant toward interracial sex, so the notion that someone can be murdered for dating someone of a different race seems far-fetched. But the fact that so many blacks are instantly willing to think the worst about Johnson’s death, and that so many Americans, black and white, still express fears about white women and black men dating and marrying, should remind us that this oldest of taboos is alive and well.