On June 28, the U.S. Supreme Court voted 5-4 in favor of the Boy Scouts of America having the constitutional right to exclude gay people. Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist interpreted the First Amendment's protection of the freedom of association to mean that the Supreme Court could not force one of America's most treasured institutions "to accept members where such acceptance would derogate from the organization's expressive message," thus overturning last year's New Jersey Supreme Court ruling that the Scouts had violated the state law banning anti-gay discrimination.

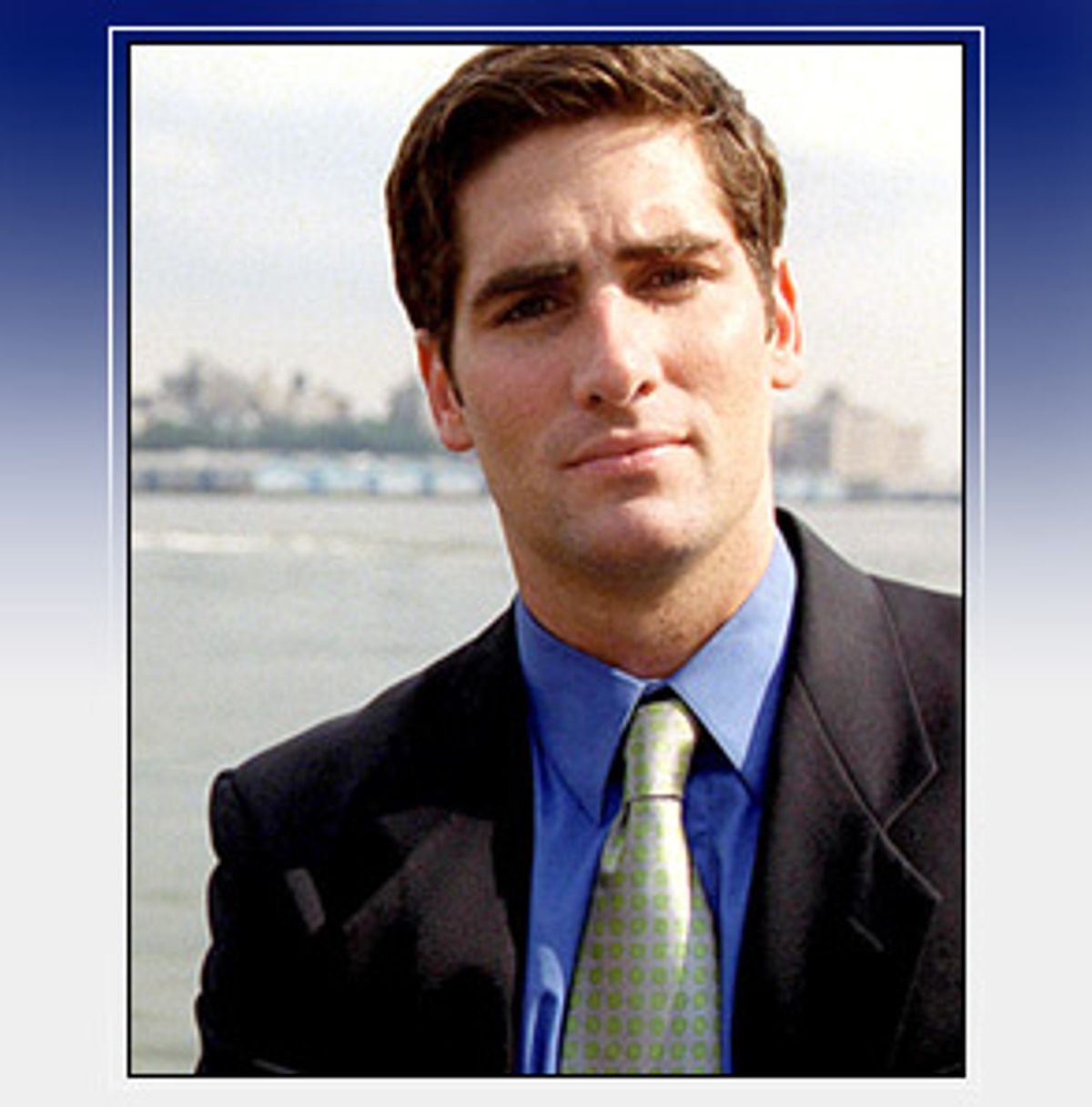

The Dale of Boy Scouts of America vs. Dale, No. 99-699 is a 30-year-old advertising director of POZ magazine and a one-time assistant scoutmaster of the Boy Scouts. I befriended James Dale in 1988 during our freshman year at Rutgers, where we were both drawn to the State University of New Jersey for more than just the classes. With its liberal reputation, and proximity to New York City, Rutgers promised to be a comfortable environment for people like us to come out.

But several months after Dale appeared in the pages of Newark's Star-Ledger as one of the most visible members of the university's Gay and Lesbian Alliance in 1990, he received two letters -- one from the Monmouth Council of Boy Scouts, the other from the district council -- informing him that "avowed homosexuals" were not permitted in the organization, and that his 12-year membership was being revoked.

The Boy Scouts taught Dale how to become a leader. Ironically, everything he learned from scouting prepared him for the fight of his life: To defend himself against the group's discriminatory policy. What began as a personal battle of a young man trying to regain his membership with the institution that defined his childhood experience has evolved over a decade into a national issue about the future of gay youth in America -- and Dale has become their most vigorous advocate.

A week after the decision was handed down, Dale and I got together for lunch. While the man sitting across from me may not have been victorious in the Supreme Court, I couldn't help but feel that his success in engaging the nation in a crucial discussion about sexual orientation and discrimination had allowed him to emerge a winner.

You've spent your entire adult life fighting for your right to remain a Scout. How did you respond to the Supreme Court decision?

On some level I'm just happy to have a level of closure. It's very easy for me to see how the past 10 years were framed by the struggle for gay and lesbian civil equality. There has been an incredible amount of progress, and the 5-4 loss in the Supreme Court shows how far we've gone. But there's still one vote, and it is a very powerful vote. We still have a ways to go.

I had prepared myself on some level that the decision could go either way, but I honestly didn't think we would lose because I believe just as much 10 years ago as I did on June 28, as I do today, that I'm right. Nobody has shaken that conviction. But it was a hard pill to swallow. If I could do it all over again, I would do it exactly the same way. My lawyer, Evan Wolfson from Lambda Legal Defense, has argued an incredible case, and I don't think any other attorney could have gotten that one other vote.

The dissenting opinion was so strong and now Americans can't think of the Boy Scouts of America without thinking of the issue of homosexuality. The Boy Scouts have forever tarnished their image with this case. Granted, I would have loved to be the victor in this case, but in the end, the only thing you're really going to remember is that they are the losers in all of this.

Is there anything more you can do?

I'm definitely going to support people's efforts because I think it is an important fight. What I find really important is that this case highlighted gay youth. When I was a gay kid growing up in suburban New Jersey, the Boy Scouts made me feel good about myself. They taught me to have self-respect and how to be a leader. The light should now shine on how America is dealing with gay youth, and what resources are there for them.

Now that the Boy Scouts have turned their back on gay kids, there has to be some other way to pick up the slack. Let's face it: I'm an adult. It was a defeat, but I'll survive. I'm more concerned about the kids in the program, where we're going as a community and where gay youth fit into that picture.

The Girl Scouts don't have an anti-gay policy, and filed a brief with the Supreme Court on your behalf. Does that give you hope? Or does that just make you more frustrated with the Boy Scouts?

The Boy Scouts were founded in England roughly 100 years ago, and England dropped their policy of banning gays about four or five years ago to make themselves relevant to the next generation of youth. The Boy Scouts of America have made a foothold in bigotry and discrimination and they are really rendering themselves obsolete for today's youth. That's a sad thing because there was so much potential there.

I see letters to the editors in papers across this country, having conversations about sexual orientation, and it is that conversation that is really the key, so I'm not totally disheartened because I believe as long as that conversation is still taking place, there will be less room for discrimination.

Kids today are coming out, and reading about gay issues in the newspapers. That really wasn't something that I had when I was growing up. As a teenager, I was looking for role models, for messages about what it means to be gay, and really the only thing I found in the '80s was a community responding to HIV and AIDS. Now, hopefully there are other ways that kids can find community and support.

There were definitely no role models for us when we were growing up in the 1980s. For girls, there were gym teachers.

And for men, there were English teachers and drama club. We didn't know where to find role models outside of that. What made it really easy for me to come out in college was learning about the gay community in New York, San Francisco, New Hope, Penn. I think now it's a little easier to learn about gay life because of the Internet.

When you got those letters from the Monmouth Council of Boy Scouts and the district council 10 years ago, did you sense that this was going to evolve into a campaign of this magnitude?

I never thought the Boy Scouts were going to rally around me with rainbow flags in hand and advocate a homosexuality merit badge. But I, of course, didn't expect their reaction, because I didn't know about this policy. That's really the basis of the entire lawsuit. I was a member of this program for 12 years and got many of the awards and honors from the program, and I taught other kids about the fine parts of this program as an assistant scoutmaster. I should have been passing along this anti-gay mission, but I didn't because it wasn't there.

If you had known that an explicit anti-gay policy existed, and the Boy Scouts were as important to you as they were, would it have impacted your gay activism in college?

Had my parents known there was this policy, they would never have me be in an organization that discriminates against a group of people, be they Jews or blacks or gays. The thing about scouting, though, is that you're taught to be active, to be a leader. In relation to gay life, everyone likes to call an openly gay person an activist.

You were the president of the university's Lesbian Gay Association, making you the spokesperson for gay activities and politics on campus at the time, though.

Yes. That letter from the Boy Scouts probably made me more of an activist. When I was discriminated against, it motivated me to be more out there, and more political about gay and lesbian issues. But I do kind of cringe at the whole label of activist because that has been used against me in the Supreme Court. I get: "James Dale is an activist. He's not a person, he's a symbol." If you're an activist, they don't need you.

During my first year in college, I was unconsciously building myself a nest of support so that when I did eventually come out, nobody would have a hard time with it. There really wasn't a lot of discrimination against me at Rutgers until this happened with the Boy Scouts.

Did you feel personally hurt by the Boy Scouts reaction to your coming out?

Yeah. I mean, the letter was signed by somebody I knew. It was the thing that I did when I was younger. To have them suddenly say, "you're gay, you're out," was painful.

But I also expected the whole thing to play out, "I'm right, they're wrong." The Boy Scouts have their own fair review process. There were three hearings, and though they said I could come to all three of them, they didn't invite me. It wasn't fair play. I went to Lambda Legal Defense right away, though when my case started, there was no Gay Rights Law in New Jersey, so it wasn't a very strong case.

Did you bide your time until there was?

No, because nobody knew that the law was going to pass. But when the law got passed in 1992, I suddenly went from having no case to a very strong case, and mine was the first under the Gay Rights Law in New Jersey.

How has this impacted your personal life over the last 10 years? Has your family been supportive?

It led my family to become advocates for gay and lesbian civil rights. When this case started, my brother wasn't out yet. He is four years older than me, and came out when he was 28.

But for me, within a matter of months of coming out to my parents, I was suing the Boy Scouts. My parents were with me at the Supreme Court. They talked to newspapers about the decision. They've been really, really wonderful about it. This whole thing has really shown what family values are all about: Taking care of your children, standing by them, being involved in their lives. My parents were not gay advocates when I was a kid. My father was in the military. When I came out to them, I got the traditional fighting from my father and crying from my mother.

It has been hard, emotionally, to appear before the country as one-dimensional. To be defined as gay is just one little piece of who I am. When I was younger, it seemed like a bigger piece, but I am a fully realized person with many different interests, and this is only one facet of who I am. Being the "Gay Boy Scout" is not the easiest label to live with for a decade. It's also weird being in the media. This public thing intersects with your private life, and it's hard to keep your life in check and in balance. When the case requires attention, it takes it.

Did you feel emotionally equipped to handle everything that comes with suing a major American institution?

Yes, for the most part. But I think if somebody said to me what this was going to be 10 years ago, it would have been very overwhelming. It has been very stressful for some of my relationships, and I also think it probably helped others. I mean, it's a part of who I am, though I think it is always weird to meet somebody who knows something public about you. It's like getting to know somebody in reverse. That's not always the easiest thing.

You and your lawyer have been a veritable two-man army. Has this made you feel like you were all alone in this? Who has been there for you?

People have submitted affidavits, and lawyers have been working around the clock filing briefs and motions. Often there are more people that have been involved with this case than I even know about. I am so indebted to so many different people. The people across the country that write letters to the editor, and the columnists that write editorials demonstrate to me that America gets it. When there's a human being discriminated against, people understand that.

There are times, though, that I have felt lonely, wondering who out there will understand this type of thing or the different pressures involved with it. I think one of the hardest things that I found is the people who offer their support, and you find you don't know what to say to them. You, or the case, means something to somebody, and you don't know how to be that something for them.

If your case had won in the Supreme Court, what would that have meant to you? Was it an issue of principle for you? Or had you really wanted to be a lifelong member of the Scouts?

It wasn't just principle. I mean, on the one hand it is. The fairest way to answer this is that I want to have a kid, and if it is a "he" and he wanted to be a Boy Scout, I would've loved to have been a part of that with him. But I wouldn't want my kid in the Scouts now because the Supreme Court has given them a license to be a small-minded organization.

With my case, it's very easy for the Boy Scouts to say, oh, he's the only one, he's the activist. But there are tons of kids who were thrown out. And it's the kids who don't have the resources or the support, and they're the ones that need it the most.

What lies ahead for you?

I'm always going to be committed to the things I believe in. I can't walk away from these issues. I would hope what I've done has motivated people to get involved, and make change. I feel like I've done my part, seeing something through from beginning, middle to completion.

I don't want to go on being the "Gay Boy Scout" for the rest of my life. Other people are very able, and the work on this issue has only just begun. For me, the most important thing is educating the public about discrimination at a time when the most American institution in this country can say they're anti-gay. It calls into question what it means to be American. The Supreme Court has essentially said, you are the anti-gay Boy Scouts of America, so now they have to live with that.

As for me, I am looking forward to getting on with the rest of my life. I am ready for a change. I have no idea what I'm going to do next, and I am very excited about that fact.

Shares