It's after midnight aboard the glittering pleasure boat Nile Maxim when the Nubian lounge singer finally finishes his set with a quavering rendition of "Feelings." Abruptly the lights dim, and the musicians switch off the electronic keyboard to take up the ancient rhythms of the reque, the rebaba and the tabla drum.

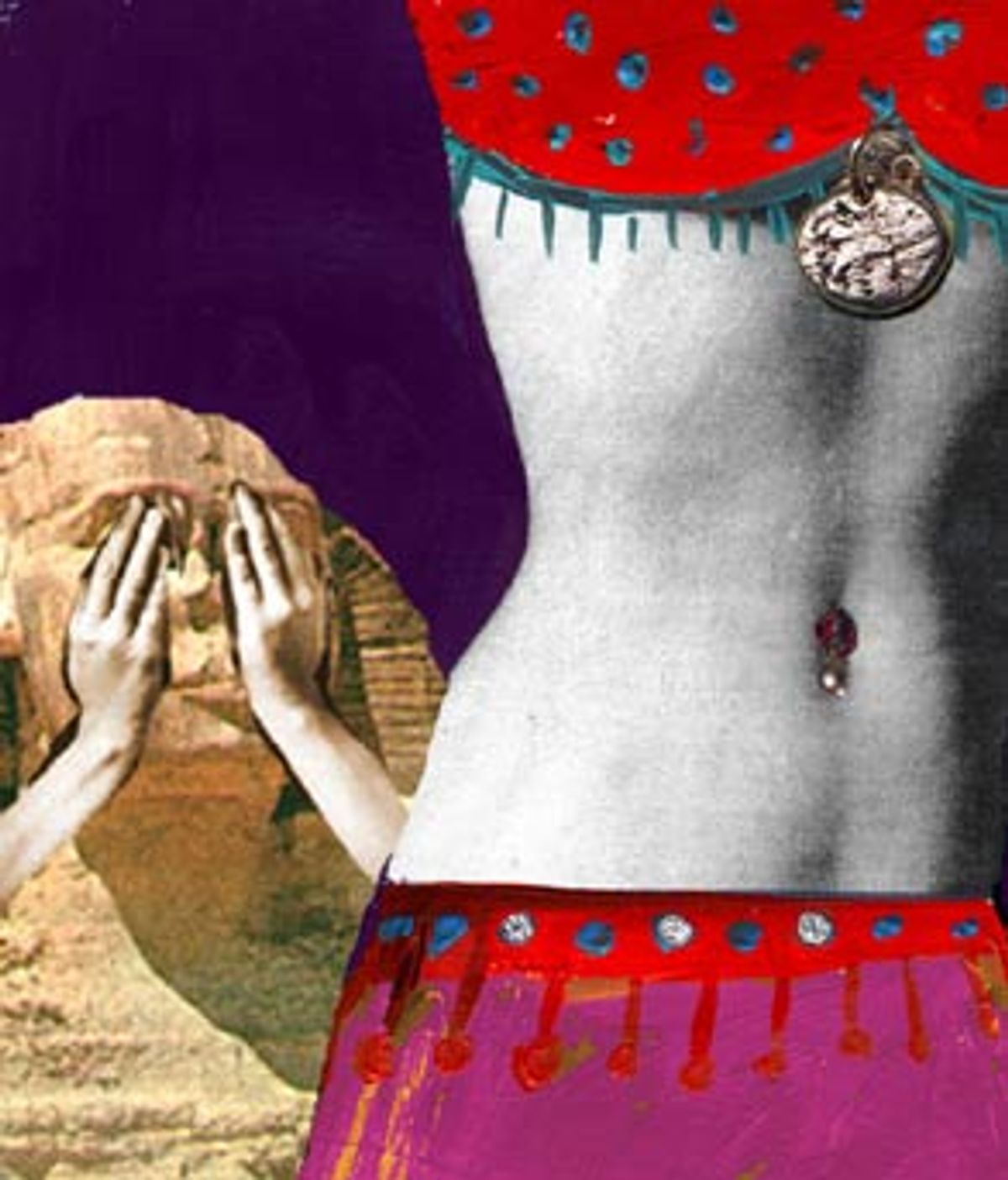

As the audience begins clapping, the Queen of the Night glides barefoot onto the stage, arms floating above long, auburn tresses, red-painted fingers flickering like snakes' tongues in the smoke-filled air. Considerable cleavage quivers within the confines of a silver-beaded bikini top whose central tassel shimmies and shivers in a little dance above the siren's navel. Dusky thighs flash from a gauzy slit skirt, while one hip, then the other, circles forward, accelerating into thrusts so violent and impudent that an Egyptian man seated next to the stage suddenly starts backward as if struck.

A quick costume change, and the dancer returns with a rhinestone-encrusted cane, swinging it overhead, balancing it on her left breast, left hip and the curve of her buttocks. Grasping the tips between her fingers, she rolls the cane up and down over her lower pelvis then arches her back underneath, finally balancing it over her fishnet-stockinged belly button for a series of suggestive lifts. Once performed by peasants with staffs cut from the sugar-cane fields, this 21st-century dance looks less like an ancient fertility rite than a time-warped vaudeville act, a combination of cheerleader baton twirling, a Caribbean limbo contest and masturbation.

It's all entertaining enough, especially for tables of foreign tourists who have no idea that the dark-haired, dark-eyed belly dancer prancing before them is no genuine Oriental houri but a self-trained British import, Liza Lazizah.

"Cairo[, Egypt] is the mother, the central nervous system of Oriental dancing," Lazizah tells me over a cigarette after the show, describing her career trajectory from minor clubs in Syria, Tunisia, Jordan and Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, where she was finally spotted by an Egyptian agent. A throaty voiced Joan Collins lookalike from London, where she first danced at a Lebanese restaurant near Regents Park, she's finally made it to the big leagues at the age of 36. "I'm not interested in going around tables, getting money stuffed down my bra," she says, sniffing at foreign dancers who angle for tips from sex-starved fans. "Oriental music gives me goose pimples. When I first heard it I was totally mesmerized. It was like a call from God."

Cairo may be to belly dancing what Hollywood is to movies and Broadway is to theater, but go to any dinner club these days and the belly dancer is likely to be an ingenue from Russia, Australia or Scandinavia. It's not so much that today's fans prefer foreign talent but that Egyptian women are abandoning the profession in droves.

In 1957 some 5,000 belly dancers were registered with the Egyptian government, compared to just 372 today. Islamic fundamentalism has forced a generation of Egyptian performers to retire and take the veil, and while package tours remain a captive audience, local interest is drying up because youngsters raised on MTV think belly dancing is old-fashioned and prefer to dance their nights away in discos.

Dwindling economic returns have led every five-star Cairo nightclub but one to close their doors, forcing the three most famous Egyptian dancers, including the 50-something Fifi Abdou, to branch into films and lucrative private weddings. Their fees -- $10,000 an hour and up -- are so high that rich Cairene families have been known to save money by flying in entire Brazilian dance troupes or American music groups like Kool and the Gang.

At a handful of remaining belly-dancing venues -- dinner cruise boats, second-rate hotels and a string of seedy nightclubs along the main road between the Nile and the Pyramids -- Egyptian impresarios increasingly showcase foreign Pygmalions. The growing cadre of outsiders includes Samasim (Little Sesames), a voluptuous blond from Sweden; Soraya, a former medical doctor from Uzbekistan; and Asmahan, an Argentine with a Latin backup band.

Connoisseurship requires a peripatetic nocturnal lifestyle and dedication verging on outright masochism. The low point of my survey of the belly-dancing scene takes place in a dive called the Cave des Rois. Swatting mosquitoes, I down Tylenol gelcaps and $15 beers while listening to a Ricky Martin clone belt away in Arabic. At 2 a.m., a silicone-enhanced Venus with Botticelli hair wiggles onto the stage. Scrunched into lime-green spandex, her Vaseline-smeared breasts conspicuously fail to jiggle along with the rest of her anatomy. Her gum-chewing performance is so lackluster that a bored client from the Arab Gulf, who has been waiting all night to throw money at her feet, grumpily tosses his wad of Egyptian 10-pound notes and leaves.

While die-hard fans wax lyrical about the great Egyptian stars of the past, the better foreign dancers are bringing respectability to a profession most Egyptians view as one veil short of prostitution. "Ninety percent of Egyptians see belly dancing as shameful," says Essam Mounir, a 37-year-old agent who has taken on Russian dancers for lack of local talent. "Foreign women are educated, they are not maids or poor girls looking for rich husbands and they show up on time and love to dance," he says. "But as for feeling our music, not one of them really gets it."

"I book foreigners for variety's sake and because they cost less," says Samy Saad, 47-year-old entertainment manager at the Nile Maxim who pays foreign dancers $220 a night, including their musicians' fees. But he snorts at rivals who hire dancers from, of all places, Japan. "Those Japanese girls have pretty faces, but they are so little you can barely see them under their costumes. I'm sorry to say it, but size matters."

As a result of foreign influence, the authentic raqs al-sharqi, or Oriental dance, has given way to a weird hybrid incorporating flamenco riffs, hand gestures from Tashkent, Uzbekistan, or the techniques of Martha Graham. But it's by no means the art form's first era of cultural cross-fertilization.

Derived from ancient fertility rites, professional belly dancing enjoyed its first seedy heyday in ancient Rome, where the satirist Juvenal described Syrian dancing girls as "nettles to whip rich men to live." The hypnotic dance was "very different from what I had seen before," commented English traveler Lady Mary Montagu in 1717. "Nothing could be more artfull or proper to raise certain Ideas, the tunes so soft, the motions so Languishing, accompany'd with pauses and dying Eyes, halfe falling back and then recorvering themselves in so artfull a Manner that I am very positive the coldest and most rigid Prude upon Earth could not have look'd upon them without thinking of something not to be spoke of."

The eroticism of the dance itself didn't disturb Egyptians. What scandalized them instead was the shame of Muslim women performing unveiled (and often naked) before infidels. Inspired by Napoleon's 1798-1801 expedition, a flood of Western travelers arrived in Egypt in the early 19th century. So many dancers crossed the line into prostitution that in 1834 Mohammed Ali, Egypt's Ottoman ruler, exiled them from the capital to towns in Upper Egypt, where they became as much a tourist attraction as Pharoanic temples.

On March 6, 1850, the Damascus-born dancer-courtesan Kuchek Hanem entertained Gustave Flaubert at her house in Esna. He praised her lovemaking but found her dancing "brutal ... far less good than Hassan el-Belbeissi, a male dancer in Cairo."

Turkish boys in drag filled the belly-dancing vacuum in Cairo until 1866, when Mohammed Ali's successor, Ismail Pasha, brought female dancers back to the capital to boost the national economy. Recognizing that dancers were earning huge sums from foreign tourists, he taxed their wages, earning the nickname "Pimp Pasha" from expatriates. About the same time, Western showmen began bringing Eastern dancing girls to Europe and America, culminating at the Chicago World Exposition of 1893, where the performances of Little Egypt attracted more notice than a 70-ton telescope.

Belly dancing became hip again in Egypt in the 1930s, not so much as the rediscovery of an ancient art but as a Hollywood-influenced nightclub act. The dance achieved a new Golden Age in the 1940s and '50s, fed on the flowering of Egyptian cinema and the showstopping charisma of stars Samia Gamal and Tahia Carioca.

Today, the purist Oriental dance probably survives in Middle Eastern homes, where men as well as women still learn the sensuous moves and listen to the lovelorn music from childhood. But the bad-girl reputation remains so deeply entrenched that few women would dream of dancing on stage.

Egyptian government regulations underscore this ambivalence. Belly dancers may not appear on television, speak during live performances or join customers after a show. A vice squad conducts nightly inspections to make sure costumes are decent, meaning that no thigh should show when the dancer is standing still.

"I'm a woman like any other with a husband, a child and a profession that requires a lot of hard work and sacrifice, and yet the government won't let me appear on TV," laments Dina Talaat Sayed, an Egyptian star with a master's degree in philosophy from Aim Shams University, who routinely breaks the law by lip-synching Arabic love songs with her navel. (The government officially requires full belly-button coverage.)

"I've never done anything immoral in my life," she tells me over tea in her tony apartment, cradling her 4-month-old son. "I'm invited to give workshops in Finland, and yet here I'm treated like a bad person. No wonder there's no new generation."

In contrast to the conservative Middle East, belly dancing has become a fad in the body-conscious West, judging by the number of Internet sites celebrating belly dancing as a form of aerobic exercise, a path to spiritual fulfillment and even a child-birth technique. Foreign teachers flock to Cairo with their students, hooking up with local travel agents to promote belly-dancing package tours.

"It's one of the few dances where you have more to give as you get older," says Angela Tromans, the British Embassy's raven-haired Cairo receptionist, who moonlights as a belly-dancing teacher for Rubenesque expatriates. "All the bittersweet things of life can be expressed. It's not about being Egyptian or foreign, it's about music, sensuality and improvisation."

And about dressing up. Overseas demand for "I Dream of Jeannie" harem pants, hand-beaded bustiers and slit skirts is now so high that the handful of remaining belly-dancing couturiers are growing rich off exports. "Ninety-five percent of my customers are foreign," says Ahmed Dia el Dine, the John Galliano of costume designers, waving a sheet of faxed orders from Australia in his atelier on Cairo's Mohammed Ali Street.

"It's true the style is no longer truly Oriental," he sighs, showing me an antique Turkish costume made from strings of rose-cut diamonds and an old piece of embroidery with the word "Allah" sewn in silver sequins. "Thirty years ago it took 35 meters [38.5 yards] of fabric just to cut the skirt for a dancer; it wasn't about naked thighs but the swirling of the cloth around the female body. The overseas customer just wants to show her flesh. I can design a costume that uses just two meters of fabric, but I struggle to avoid pornography."

"Still, I wish more Egyptians shared this enthusiasm for Oriental dancing," he says, pointing to autographed photos of grateful clients in Israel, Denmark and Austria. "But the situation has started to improve. I know this because Egyptian brides have started coming to me. They order belly-dancing costumes for their trousseaus."

Shares