Reading Aimee Bender's feverish, Loony Farms fiction, you can practically see her frantic fingers working over each sentence. At her best, Bender makes you root for her to keep furiously pressing down on the keyboard; you hope she'll make things so crazy that you'll turn the page and find all the words capitalized, or garbled, or bursting into fire. But Bender's prose, always beautiful, always original, stays contained in its typeface, where it might be even scarier.

In her first book, "The Girl in the Flammable Skirt," Bender created a world made of emotional spurts. The stories in that collection were full of mermaids, imps and strange allegories that blurred into the mundane, contemporary lives of women sitting at desks, getting engaged, living in shadowy, lonely apartments. Bender's women live out their warped thoughts -- they fly, they spit, they shred their dresses. They always dream violently and have dangerous quirks; they're barely civil and ready to burst. One of Bender's characters would tear off the head of a shoe-obsessed "Sex and the City" chick in two seconds flat.

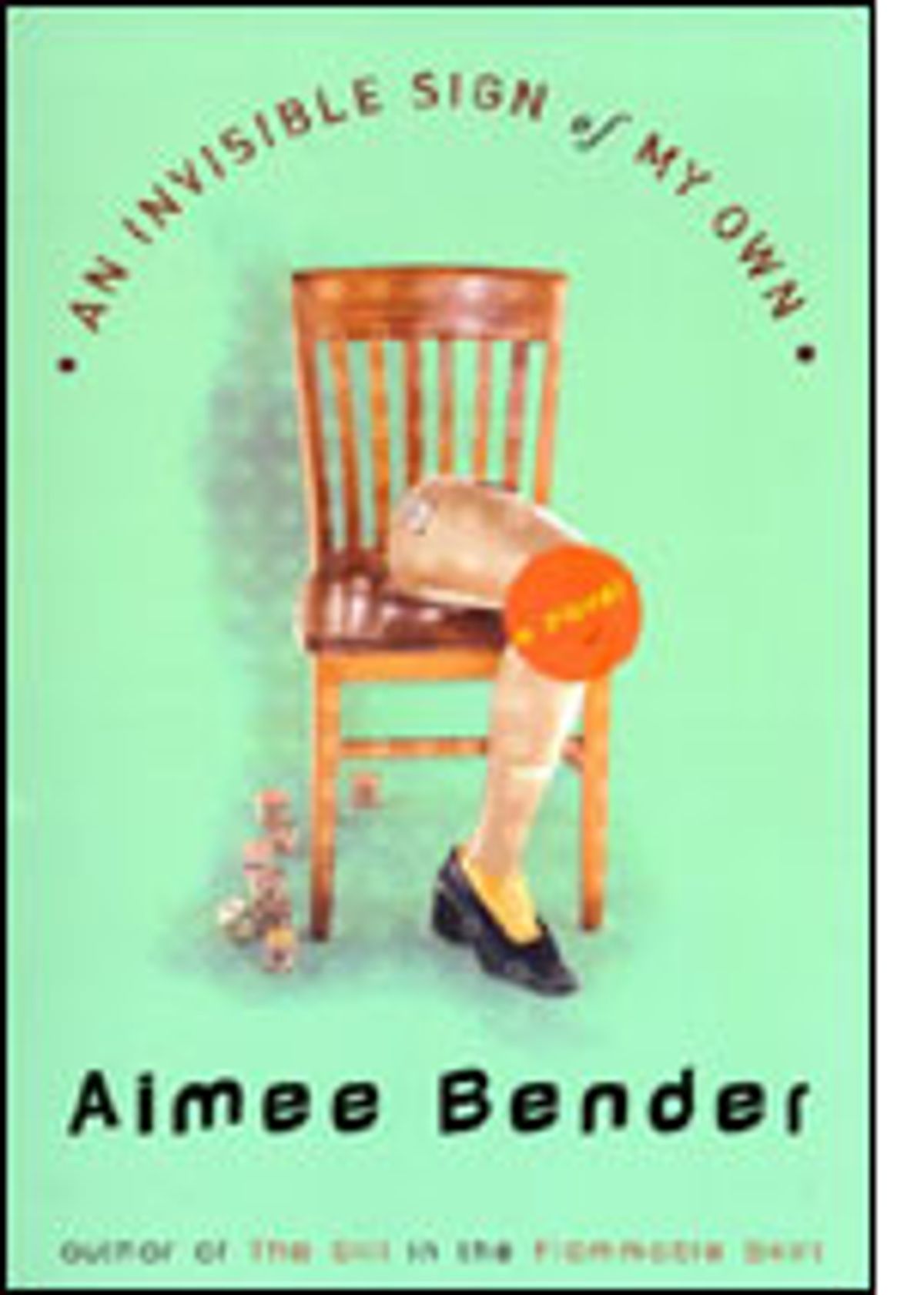

Bender once again creates a woman passionately on the brink in "An Invisible Sign of My Own," her first novel. This time it's Mona Gray, an obsessive-compulsive who knocks on wood until her knuckles are raw and bleeding, sleeps with the light on, washes her mouth out with soap whenever she feels sexual desire and takes an ax home for her 20th birthday, contemplating cutting off body parts in an attempt to mentally stave off her father's impending death from a mysterious illness. Death, to Mona, is the ultimate loss of control: "A sharp, dark sliver; a loose, pale pellet. On the day of your death, it melts out through your entire body, a warm, broken bath bead."

Mona calms herself with numbers and geometry, with which she feels a visceral connection. She counts out everything, feels "practically married" to the octagons that form stop signs and sees traffic cones as "vivid and isosceles." Mona becomes a math teacher, excelling in the classroom, especially with her rambunctious and restless second-grade class, where she has the ultimate challenge of taming chaotic 7-year-olds with math. She succeeds by having them create numbers out of material -- sticks, I.V. tubes -- and what at first seems eminently manageable turns unstable as Mona involves herself in her students' lives. Her math lessons become emotional explorations, and her associations with numbers begin to shudder with despondency, so that a 50 becomes a feeling of doom; a 42, panicky elation.

She meets Benjamin Smith, the handsome science teacher with chemical burns on his arms. They date and make out, but like death, sex for Mona is a poetry too formless and uncontained to face. She describes sleeping with her first boyfriend as poisonously awesome: "His skin was a buoyant ship over mine, and he kissed threads of silver into the back of my neck." Afraid she will explode into meaninglessness again, she barely gets that far with Benjamin before having to run into the bathroom and scrub out her mouth with soap.

At times, the plot of "An Invisible Sign of My Own" seems too imposing to allow Bender's unwound, poetically wandering prose to flower. As Mona moves from the violent, scratchy internal world of her home to her responsible classroom persona, she flips too quickly from crazy to controlled, and we lose our grounding occasionally. In one scene, her lovable class turns violent, and Mona seems strangely frozen, waiting for a Benderian opportunity to scoot out of the plot and do something wholly unpredictable.

The novel works best when Bender shakes free of the need to assign everything nicely into chapters, instead devoting pages to depicting Mona as she worries about death, stares at the slanted parallelograms of her alarm clock's digital display or, at the very end, creates a heartbreaking fairy tale to comfort one of her students. In these moments, her writing becomes translucent, reminding us that she's the rare writer who, no matter how far beyond plausible a situation is, reveals her own pain and heart in describing it. In "An Invisible Sign of My Own," Bender's main character must hold all that warped twitchery within the structured confines of a novel -- a difficult task that Bender accomplishes nicely, though you wish, in a way, she didn't feel she had to.

Shares