The price of increased security at nuclear weapons labs, some scientists say, is talent. Alleged security lapses, they say, have left in their wake a hostile and paranoid climate for workers, which is damaging national security by driving designers away.

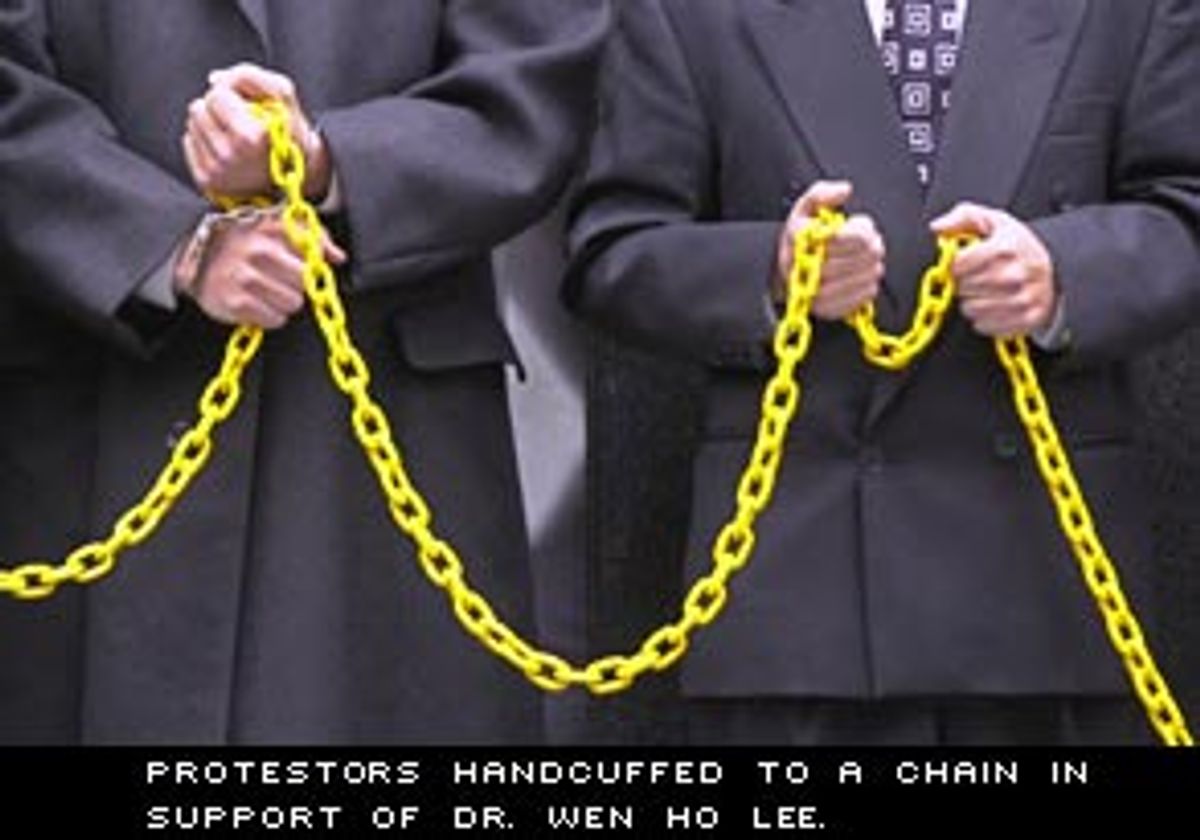

Two crises brought weapons-lab security under fire: First, the ongoing case of Wen Ho Lee, a Taiwan-born scientist fired from the Los Alamos, N.M., lab last year for copying classified nuclear weapons info to portable tapes, several of which are missing. Lee has been in jail since December and awaits trial on 59 felony counts.

The second is the case of two missing computer hard drives containing classified information that went missing as a fire roared near the lab. Employees failed to alert officials that the disks were missing for three weeks. Fear abounded that the disks had been shared with foreign powers, but when they finally surfaced two weeks later (behind a copy machine in a secure area) an FBI investigation concluded that they had not been tampered with.

But that didn't stop the alarm bells ringing in Congress. Hearings about the security lapses are ongoing, and the calls for greater vigilance at the nuclear weapons lab have come both from Republicans and from the Clinton administration, which has been attacked for years for alleged inappropriate ties to China. On Wednesday, University of California officials complained that budget cuts have made it impossible to maintain sufficiently tight security at the labs, which the university runs jointly with the U.S. Department of Energy.

Still, some scientists say the security problem is being exaggerated for political reasons. "What's going on in Washington with all the hearings, it's completely unrelated to any real problem at the labs," asserts Hugh Gusterson, a professor of science and anthropology at MIT. "It's all about party political advantage. If you look at the statistics this year, the security violations have been less in number than in previous years. I know the media has conspired to give this impression that security has gotten lax at the labs, but I don't believe it's true."

Gusterson thinks politicians are shooting themselves in the foot. "The Republicans in Congress and the administration between them are pretty much wrecking the nuclear weapons program. If you're against nuclear weapons I guess they're doing the right thing," Gusterson said. "But it is ironic to have disarmament by Republicans who are doing it in the name of increased national security."

The pressure on the DOE is causing a backlash in the scientific community. An article in Sunday's New York Times documented the dwindling number of Asian and Asia- American scientists applying for and accepting jobs at Los Alamos. Academic groups are calling for a boycott of the national weapons labs because they say a system of racial profiling is going on, with scientists of Asian descent systematically harassed and denied advancement. DOE officials have denied the allegations.

Asians and Asian-Americans make up more than a quarter of science and technology doctorates at the nation's top universities. Without them, the talent pool of weapons designers would be drastically depleted.

"Disgracefully, there is evidence that the racial profiling issue is real," says Steve Aftergood of the Federation of American Scientists. "This is not a concoction of hyper-sensitive activists. The larger issue is the vitality of the lab, and it's just amazing to me that that is being missed by Congress."

But it's not just Asians and Asian-Americans who are feeling the scrutiny. Across the industry, talented scientists are looking at the government's treatment of Wen Ho Lee, polygraph testing of lab employees and the security response as proof that working for the government carries too much risk and not enough reward.

"I'm told that a lot of the weapons designers are talking about looking for new jobs, especially the younger ones," Gusterson says. "And the older ones are talking about early retirement.

What's more alarming than the security breaches themselves is the level of paranoia about them, according to Jessica Stern, senior fellow at Harvard's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. "There's nothing more critical to U.S. national security than protecting legitimate secrets," says Stern. But the current uproar over lapses at Los Alamos is only making matters worse.

"There does seem to be a kind of McCarthy-type atmosphere developing," Stern says. "I think there is a fine line between prudence and paranoia. We may be slipping over the paranoid edge of that line."

Stern now works on national security and terrorism issues. But from 1992-94, she worked at the Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, Calif., one of three national labs that develop nuclear weapons technology -- the others are Los Alamos and Sandia (which has sites in New Mexico, California, Nevada and Hawaii). She says she's heard from colleagues that the Lee case has angered many scientists who believe, whether he is guilty or innocent, that the way he has been treated is grossly unfair.

Lee has been in jail since December on charges that he copied secrets "with the intent to injure the United States." Only after the U.S. District Court judge in the case ordered prosecutors to be a little more specific were Lee and his lawyers told, on July 5, which countries he allegedly tried to give the information to back in 1993.

The prosecution's theory has been that Lee was giving secrets to Chinese labs. But now, the list of countries prosecutors say Lee might have been spying for has grown amusingly broad -- Taiwan, Australia, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Singapore and Switzerland -- due to evidence that he sent tapes of his work to all those countries.

Lee's defenders say he was concerned he might lose his job because of cutbacks at Los Alamos, and had been sending his résumé -- including taped samples of projects he was working on -- to labs in those countries at the time of his alleged breaches. Lee has not been charged with espionage, but he still faces the possibility of life in prison. The case is set to go to trial in November. Until then, he remains in solitary confinement. Officers put shackles on him during the one hour each week in which he visits his family.

His case has sent ripples of fear through the nuclear scientific community, according to Stern. "I think it is definitely creating an atmosphere that is not conducive to science and that it will stifle creative scientific research."

Some scientists say Lee's security breach is cause for concern. "The information he downloaded he shouldn't have downloaded," Gusterson says. "I don't know anyone at the lab who thinks that it was OK for him to download it. I think every scientist at the lab cuts a corner every now and then on security rules. But what Wen Ho Lee did is really serious. If you say that some weapons scientists do the equivalent of going 65 miles an hour in a 55 mile a hour zone, what he did was like going 120 miles an hour in a 55 mile an hour zone."

Still, Gusterson thinks the reaction to the Lee case has been unfair. Employees at Los Alamos are under strict orders not to talk to the press. But Gusterson says people he knows there are finding the increased security measures very difficult to work in. For example, he says, since the Lee scandal erupted, computers at Los Alamos no longer contain floppy disk drives, making it very difficult to work on a project on more than one computer. Employees are now required to turn off their computers and lock their safes every time they get up to go to the bathroom. "It makes it really hard to get your work done," Gusterson says.

Besides that, Gusterson says, the Wen Ho Lee case has lowered morale. "That image of him shackled while he meets with his family haunts a lot of scientists at Los Alamos. They're determined that they are not going to be the next person in that picture."

And some observers say security lapses at Los Alamos have been a problem, but that the situation is not so dire as to endanger national security.

"People seem to have gotten a bit loose in the handling of secrets and classified information," says Gideon Rose, deputy director of national security studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. "There's no excuse for lax security. It's not ideology -- it's just basic competence.

"This is something that's always a bit of a problem," but not cause to get paranoid, Rose says. "It's bad practice and sloppy security practices rather than an imminent threat to the country."

He sees the larger problem as part of a built-in tension between science and security. "The fact is, civilians and scientists do not take security as seriously as professional intelligence people," he says. "They're just not trained to think that way, and they're lax. But that's no excuse for not riding hard on them. It's very difficult to keep up the kind of semi-paranoid attitude that makes you keep your secrets secure. Especially in a time of general peace and prosperity."

"That's definitely true," Stern agrees. "There's a natural, unavoidable tension between the desires and the needs of scientists and the legitimate concerns of security personnel." Scientists essentially try to uncover secrets in a collaborative environment. "Without openness, it's hard to push back the curtain of ignorance, which is what scientists aim to do. It's hard to advance at the same time when scientists are working on matters related to national security, when secrecy is critical. So there is this tension that you can't avoid."

But Los Alamos spokesman Jim Danneskiold thinks that tension is overstated. "In some ways, saying there's incompatibility between science and security at a place like Los Alamos is misleading," Danneskiold said. "Security is part of everybody's job here. The people who deal with classified information are trained and know how to handle it."

He sees accountability as the key. "There is no security system that can prevent people from breaking the rules."

In Stern's opinion, one problem is confusion about what information truly needs to be classified. In the early 1990s, President Clinton announced a widespread declassification of scientific data that weren't such big secrets anymore. Even so, "there's much too much that's called classified," complains Stern. "The classification guidelines are not up to date -- sometimes they're too onerous and sometimes they're not onerous enough.

"In the area of nuclear weapons," Stern explains, "we have this whole history that anything related to nuclear weapons is classified. Sometimes it's based on outdated concern. Whereas, in the area of biological weapons, I think more should be classified than is."

Danneskiold says the issue there isn't what's classified, but as how such information is handled. At a Congressional hearing July 11, two senior officials from the DOE testified that part of the explanation for the lapses is the rollback of "strict formal accountability" procedures that occurred government-wide in the early 1990s. Those procedures ensured that every document was signed in and signed out, clearly marking the paper trail.

While such a system is harder to maintain in the digital age, Danneskiold believes it is desirable. "If you asked us even today, would the lab prefer strict accountability, I think we'd say yes," Danneskiold said. "Clear rules are what people look for."

But critics say the rules are strangling scientists.

"The rules now are stricter than they've ever been in living memory," Gusterson says. "It's not that they're gong back to the situation in the early '90s. They're getting much stricter than that."

With morale so low and fears running high, some of the most talented weapons designers might decide to bail out of government work.

Aftergood thinks the loss of such talent "is the most important issue which is in danger of being overlooked in the current security mania. I think many members of Congress and others are prone to forget that security is a means and not an end in itself. If security becomes an overriding concern, then the mission of the laboratories will suffer."

Stern agrees. "We need to make sure that the laboratories are still an attractive place for America's most promising scientists," she says. "We want to make sure that they feel comfortable working there."

Shares