In April 1966, back on the job after their first vacation in five years, the Beatles embarked on the first session for their "Revolver" album. They began recording the hypnotic, apocalyptic "Tomorrow Never Knows," a new John Lennon song that was unlike anything the band had ever attempted. Lennon's lyrics were inspired by the "Tibetan Book of the Dead": "Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream/It is not dying/It is not dying." He wanted his voice to sound like the Dalai Lama singing from a high mountaintop with 4,000 monks chanting in the background. To achieve the dizzying, oracular effect, they ran Lennon's vocals through a rotating Leslie speaker (normally attached to a Hammond organ); the saturated sounds of tape loops turned guitar notes into shrieking gulls.

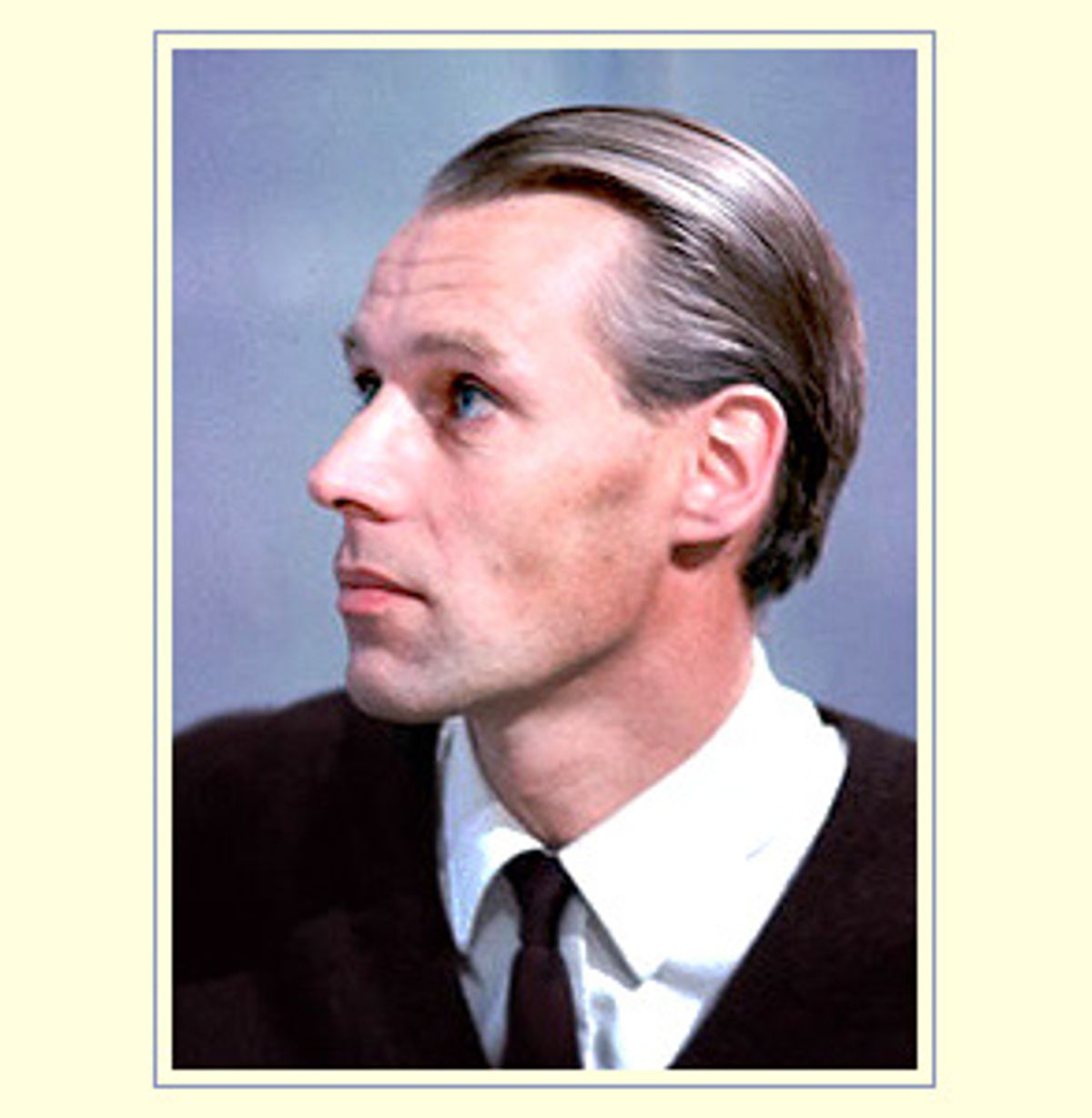

The man who organized and thrived on all this madness was producer George Martin, whose relationship with the Beatles, always integral, was now entering uncharted territory. The aptly titled "Tomorrow Never Knows" closes the masterpiece "Revolver" with a tantalizing hint of the artistic statement Martin would help them realize next: "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band."

"It would be wrong to assume that the Beatles alone were responsible for this remarkable recording, or for the progressiveness which would be the hallmark of much of their future output," Mark Lewisohn says of the song in "The Beatles' Recording Sessions," a day-by-day account of the group's entire career that is definitive and required reading for serious fans. "George Martin was, as ever, a vital ingredient in the process, always innovative himself, a tireless seeker of new sounds and willing translator of the Beatles' frequently vague requirements."

With the exception of Phil Spector's syrupy post-production on the "Let It Be" album, Martin produced every Beatles recording -- from the first single ("Love Me Do") to the last album ("Abbey Road"). Manager Brian Epstein, their most fervid salesman, may have given the scruffy Liverpudlians an initial gloss, but Martin gave them real artistic polish. He supervised the band's transition from precocious boys to mature artists, harnessing all that wild genius into the most efficient and dazzling hit-making unit in modern pop.

In all he produced more than 700 recordings in a career spanning 50 years and genres as diverse as jazz, rock, classical, comedy and film soundtracks, with an unprecedented 30 No. 1 Beatles and post-Beatles hits to his credit in the U.K. Now known as Sir George, Martin may be the most influential and prolific record producer in history.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

George Martin was born on Jan. 3, 1926, in Holloway, North London. The son of a carpenter, he grew up poor, without formal musical training. He taught himself to play piano by ear, and at 16 started his own school dance band, George Martin and the Four Tune Tellers. From 1943 until 1948, he served with the British Fleet Air Arm as an observer in planes, rising to the rank of lieutenant. Paul McCartney later credited Martin's legendary composure to his military service: "He pulled it all together -- you're ultimately responsible, you're the captain. I think that's where George got his excellent bedside manner," McCartney is quoted as saying in Philip Norman's "Shout!" "He'd dealt with navigators and pilots ... he could deal with us when we got out of line."

After his military service Martin studied composition and classical music orchestration at London's Guildhall School of Music; his first job after graduating was at the BBC's music library, where he further cultivated the clipped, upper-crust accent that belied his humble roots. He entered the music industry in 1950, as assistant to the head of EMI's Parlophone Records, and was soon made responsible for the label's classical recordings. He worked with artists like Stan Getz and Judy Garland, establishing himself as a jazz, classical and light music producer. But he also sought new markets, in an effort to shore up what was then known as EMI's junk label. Martin produced a string of hit comedy records with Peter Ustinov, Peter Cook, Dudley Moore and, most notably, the Goons.

In 1955, after a management shake-up led to his boss's retirement, Martin was appointed head of Parlophone at 29, becoming the youngest manager of an EMI label. In 1960 the Temperance Seven gave him his first No. 1 hit in Britain with "You're Driving Me Crazy." After watching the rise of another EMI label's act, Cliff Richard and the Shadows, Martin was eager to acquire a pop group for Parlophone -- just as Epstein was desperate to find a recording contract for the Beatles. Epstein had been turned down by major British labels Decca, Pye, Phillips and even EMI -- twice. Martin scheduled an audition for June 6, 1962.

Despite feeling that the Beatles' demo tape had been "pretty lousy" and "very badly balanced" and contained "not very good songs" by "a rather raw group," Martin has recalled, "I wanted something, and I thought they were interesting enough to bring down for a test." You know what happened next: He was won over by their Liverpudlian charm. "I liked them as people apart from anything else, and I was convinced that we had the makings of a hit group," he told British music magazine Melody Maker in 1971. "But I didn't know what to do with them in terms of material."

Because Martin has a somewhat professorial demeanor, the obvious differences between him and the Beatles have always been played up, but in truth they had much more in common than it appeared. "I've been cast in the role of schoolmaster, the toff, the better-educated, and they've been the urchins that I've shaped. It's a load of poppycock, really, because our backgrounds were very similar. Paul and John went to quite good schools. I went to an elementary school, and I got a scholarship for that, and I went to Jesuit college. We didn't pay to go to school, my parents were very poor. Again, I wasn't taught music and they weren't, we taught ourselves," Martin told Billboard magazine. "As for the posh bit, you can't really go through the Royal Navy and get commissioned as an officer and fly in the Fleet Air Arm without getting a little bit posh; you can't be like a rock 'n' roll idiot throwing soup around in the wardroom."

Lennon was particularly impressed that Martin had recorded Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers from BBC Radio's "The Goon Show." "The Beatles instantly developed a rapport with George Martin," Peter Brown, former director of the Beatles' management company, writes in "The Love You Make." Martin told them they needed to lose then-drummer Pete Best, and they did. Though only 14 years older than Ringo Starr, the oldest Beatle, Martin was light-years ahead of them in technical sophistication. "The various magic tricks that Martin could perform in the control room," Brown writes, "made him seem like the Wizard of Oz behind his control panel."

In the beginning, Martin was tough on the group. "As composers, they didn't rate. They hadn't shown me that they could write anything at all," he told Melody Maker. "'Love Me Do' I thought was pretty poor, but it was the best we could do." Martin saw the kernel of something, but even he had no clue just what kind of phenomenon he was about to help unleash. "The question of them being deep minds or great new images didn't occur to me -- or to anybody, or to them, I should think."

When they laid down "Please Please Me" in February 1963, Martin told them they'd recorded their first No. 1. He quickly resolved to make a Beatles album, which he produced in a one-day session. "There can scarcely have been 585 more productive minutes in the history of recorded music," Lewisohn writes. Known as a producer of live stage recordings, Martin tried to capture the manic excitement of a Beatles performance, even briefly considering taping at the Cavern Club. He got what he was looking for, particularly in Lennon's larynx-gnashing finale, "Twist and Shout."

In March, Martin was proved right; "Please Please Me" hit No. 1 on several lists. That year Martin would go on to spend an incredible 37 weeks at No. 1 as producer of the Beatles and other acts, including Gerry and the Pacemakers and Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas. By June, Parlophone was dominating the British pop charts, just 12 months after the Beatles auditioned.

In September, Lennon and McCartney played Martin a song they'd recently written in a hotel room. Martin suggested they bring the catchy chorus -- "She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah" -- up to the front of the song. "In 'She Loves You' George Martin had been able to incorporate in magic proportions all the ingredients of the three previous singles into one ineluctably attractive song," Brown writes. "'She Loves You' didn't climb the charts, it exploded with a fury into the No. 1 position, selling faster and harder than any single ever released." It became the band's first million seller.

For the next few years, Martin and the Beatles worked nonstop, churning out hit after hit. Unhappy with his EMI salary, he formed his own production company called AIR (Associated Independent Recording) in 1964 with producers Ron Richards, John Burgess and Peter Sullivan. Though under contract to make records for EMI, the Beatles continued to be produced by Martin. In the late '60s, he oversaw the design and construction of AIR Studios in London, which became one of the most successful studios in the world.

Martin recently offered this appraisal of his job: "The producer is the person who shapes the sound. If you have a talent to work with -- a singer together with a song -- the producer's job is to say, right, you need to put a frame around this, it needs a rhythm section to do this or that and so on," he told the Irish Times in 1999. "He actually decides what the thing should sound like, and then shapes it in the studio. He may also be an arranger, in which case he may write the necessary parts ... he shapes the whole lot. It's like being the director of a firm."

His input at the time consisted of crafting song structures, organizing beginnings and endings, harmonies and solos. He suggested a string quartet for McCartney's "Yesterday," then a radical idea for a rock group, and contributed the occasional harmonium, organ or piano part, including the Elizabethan-style solo on "In My Life," which was cleverly sped up to achieve a quick, bright precision. He also wrote the orchestral scores for the Beatles movies "A Hard Day's Night" and "Help!" (and, later, "Yellow Submarine" and, with McCartney, "The Family Way" and "Live and Let Die"). His role as Beatles producer, which had long since eclipsed all his other work, was about to gain a new complexity, thanks to new studio technologies (including four-tracking) and the Beatles' desire to quit touring and devote themselves entirely to studio recording.

When Martin turned up at EMI's Abbey Road Studios for the first time, he said during a recent lecture tour, recording devices were powered not by electric motors, which were too unstable to cut 78 rpm records, but by a slow-falling weight that descended from the studio's roof to its basement. Records were heavy things that shattered if you dropped them. When the Beatles came along in 1962, things hadn't improved much.

By 1965, "Rubber Soul" had gone far beyond the early live-performance albums. Rhythm, vocal and instrumental tracks were carefully layered over several weeks. The process, not to mention the music, altered the direction of rock. Martin was also bringing in more session players, changing the Beatles' sound to reflect their leap in craftsmanship. Inspired by American film composer Bernard Herrman's score for "Fahrenheit 451," he composed a beautifully understated string accompaniment for "Eleanor Rigby." (To hear just how understated, compare the song with Phil Spector's gaudy orchestration of "The Long and Winding Road" on "Let It Be," which horrified Martin and McCartney.)

But it was "Strawberry Fields Forever" that put Martin's ingenuity to its most crucial test. Written by Lennon while he was in Spain making a Richard Lester film called "How I Won the War," two versions of the song had emerged in the studio. One was a heavy amalgam of psychedelia inspired by the San Francisco music scene, the other softer and more traditionally Beatlesque, with trumpets and cellos. Lennon ended up liking the beginning of the first version and the ending of the second. Problem was, they were at different speeds and a semitone apart in key. Martin eventually solved this conundrum by speeding up one and slowing down the other, splicing the halves together into a seamless whole. With "Strawberry Fields," "George showed us once and for all that the recording studio itself was a musical instrument," producer Tony Visconti recently told Billboard. "This track was the dividing line of those who recorded more or less live and those who wanted to take recorded music to the extremes of creativity." The "Sgt. Pepper" sessions had begun.

Inspired by a circus poster he'd found in an antique shop, Lennon wrote "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite," telling Martin he wanted to smell the sawdust in the ring. The producer obliged him, procuring sounds of old Victorian steam organs. He put them all on one tape, had it cut into 15-inch sections, had the pieces thrown into the air and joined back together as one; some were backward and some were forward. The unusual sounds permeate the background. To get the song's wildly atmospheric whooshing effects, Martin next played chromatic runs on a Hammond organ at half-speed, the same trick employed for "In My Life." "I was quite pleased with that," Martin told Melody Maker. "It was a sound picture thing, and I was doing really what I'd been doing with Peter Sellers."

The real circus came in the form of one legendary session for "A Day in the Life." With 24 bars to fill between Lennon's verses ("I read the news today") and McCartney's middle eight ("Woke up, fell out of bed"), the duo suggested "a tremendous shriek, starting out quietly and finishing up with a tremendous noise." Martin booked a 41-piece orchestra and scored chaos for it to play. He began each instrument at its lowest note and, at the end of the 24 bars, had it hit its highest note related to an E chord. Martin told the musicians to do whatever it took to get from point A to point B. A gaggle of celebrities was on hand, including Mick Jagger, Marianne Faithfull, Donovan Leitch and Mike Nesmith. McCartney brought in funny hats and fake noses, "and I distributed them among the orchestra. I wore a Cyrano de Bergerac nose myself," Martin told Melody Maker. "Eric Gruneberg, who's a great fiddle player, selected a gorilla's paw for his bow hand, which was lovely. It was great fun."

"Pepper" was released in 1967. Four years had intervened between the Beatles' first, nine-and-three-quarters-hours album session for "Please Please Me" and "Sgt. Pepper," which clocked in at 700 hours. From that collaborative peak, the Beatles began slowly going their separate ways; though Martin's role didn't change fundamentally, everyone was having less fun. During the White Album ("The Beatles") sessions, Lennon and McCartney isolated themselves from each other; all four Beatles were rarely in the studio for recording together, a process much the reverse of their earliest days.

By the time the Beatles got around to "Get Back," a literal attempt to go back to their rock 'n' roll roots (later retitled "Let It Be"), they were a mess, as evidenced by the 1970 film of the sessions, whose lone highlight is the famous rooftop set. The sessions were shelved, to be later reproduced by Spector, who for all his wall-of-sound artistry couldn't do much to salvage the tracks. The band then decided to let Martin do some actual producing, and they were graced with a suitable finale in "Abbey Road."

In the '70s and '80s, Martin produced albums by the Mahavishnu Orchestra, America (seven albums), Jeff Beck (two), Neil Sedaka, Jimmy Webb, Cheap Trick, Kenny Rogers and Paul McCartney ("Tug of War" and "Pipes of Peace"). One of the best of these, Jeff Beck's "Blow by Blow," was an artistic success and a bestseller that hit No. 4 in 1975. Martin opened an AIR Studios in Montserrat in 1979; it was destroyed when a hurricane ravaged the Caribbean island in 1989. In the mid-'90s, Martin returned to the vaults and to his familiar role, unearthing and preparing previously unreleased Beatles tracks for the three-volume Anthology series. The first volume entered the U.S. album chart in December 1995 at No. 1.

He was knighted in 1996, and received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grammys the same year. A year later, Martin produced his 30th No. 1 hit in the U.K., Elton John's "Candle in the Wind 1997," a charity single recorded after Princess Diana's death that became the bestselling single of all time and, in Martin's words, "probably my last single. It's not a bad one to go out on." The same year, in response to the second of two volcano eruptions since 1995 that had further devastated Montserrat, Martin put on a benefit concert for the island with McCartney, Eric Clapton, Elton John and Sting.

After five decades in the music industry, Martin bowed out of record production in 1999 with "In My Life," a collection of Beatles songs recorded by comedians like Robin Williams and Jim Carrey and musicians such as Jeff Beck and Phil Collins. (Beck's version of "A Day in the Life" was nominated for a Grammy award in the best pop instrumental performance category.)

Martin is still with his wife of more than 30 years, Judy Lockhart-Smith, his former Parlophone secretary. One of his four children, Giles, has also entered the business. In an interview on the promotional site for "In My Life," Martin made him sound like a chip off the old block: "You've got to get on with people and you've got to lull them into a kind of sense of security and you've got to get rid of their fears, you've got to relate to people, and he certainly can do that."

Martin may not be producing records, but he isn't exactly retiring; he still oversees AIR Studios, and last year he became chairman of the advisory board of Garageband.com, a new Internet music initiative designed to seek out new talent outside the confines of the corporate record industry. The Beatles were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988; Martin finally made it in 1999, alongside Sir Paul McCartney.

In not only chancing his career on the Beatles -- then "an industry joke" as Martin has put it -- but also giving a voice to their every musical whim, Martin has rightfully been referred to as the fifth Beatle. Martin blends giddy enthusiasm with cool intelligence and eloquence. His contributions to Beatles lore are intriguing and articulate; in documentaries such as "The Compleat Beatles" and throughout the marathon "Beatles Anthology," he is mesmerizing when he leans over his mixer and calls forth individual tracks, be they orchestral swells or lone, spine-tingling vocals. He had the front-row seat.

I was on hand when Martin brought his lecture tour, "The Making of Sgt. Pepper," to New York's Town Hall in 1999. Each time he introduced a song, from "Penny Lane" through to "A Day in the Life," there was a round of applause, and Martin would say, "Yes, that's a great one," or "Really marvelous, isn't it?" -- as if, all these years later, he was as truly amazed as all of us have always been. At one point, after he'd given an introduction to "Strawberry Fields," a frenzied audience member shouted "Amen!" Martin replied, "Amen." Walking out into Times Square on a cold winter night, I marveled at how it had been exactly 35 years and 10 blocks from this spot that Sir George's boys blew down the doors and called in the invasion from Ed Sullivan's stage. "They say if you can remember the '60s, you weren't there. Well, I was there," Martin had assured his audience. Some of the audience had been there too, but even the younger ones knew exactly what he meant when he said, "It all happened so quickly, that flowering of genius so long ago."

Shares