Probably no one knows better than the Bush family about the importance of appearing healthy during an election campaign.

In 1992, President Bush's reelection bid began badly when he vomited and collapsed in Japan at a dinner party thrown by the country's prime minister. From then on, the campaign was dogged with mostly unconfirmed rumors of his ill health. It was speculated, for example, that atrial fibrillation medications he took were affecting his mental acuity. What else would explain his pallid and lackluster performance at debates and appearances, particularly compared to the robust physical health and voracious appetite exuded by opponent Bill Clinton? The Bush campaign headquarters vigorously denied every ill health charge but it didn't change the fact that it wasn't only the economy that was ailing -- it was also Bush's physical image. His election results were equally anemic.

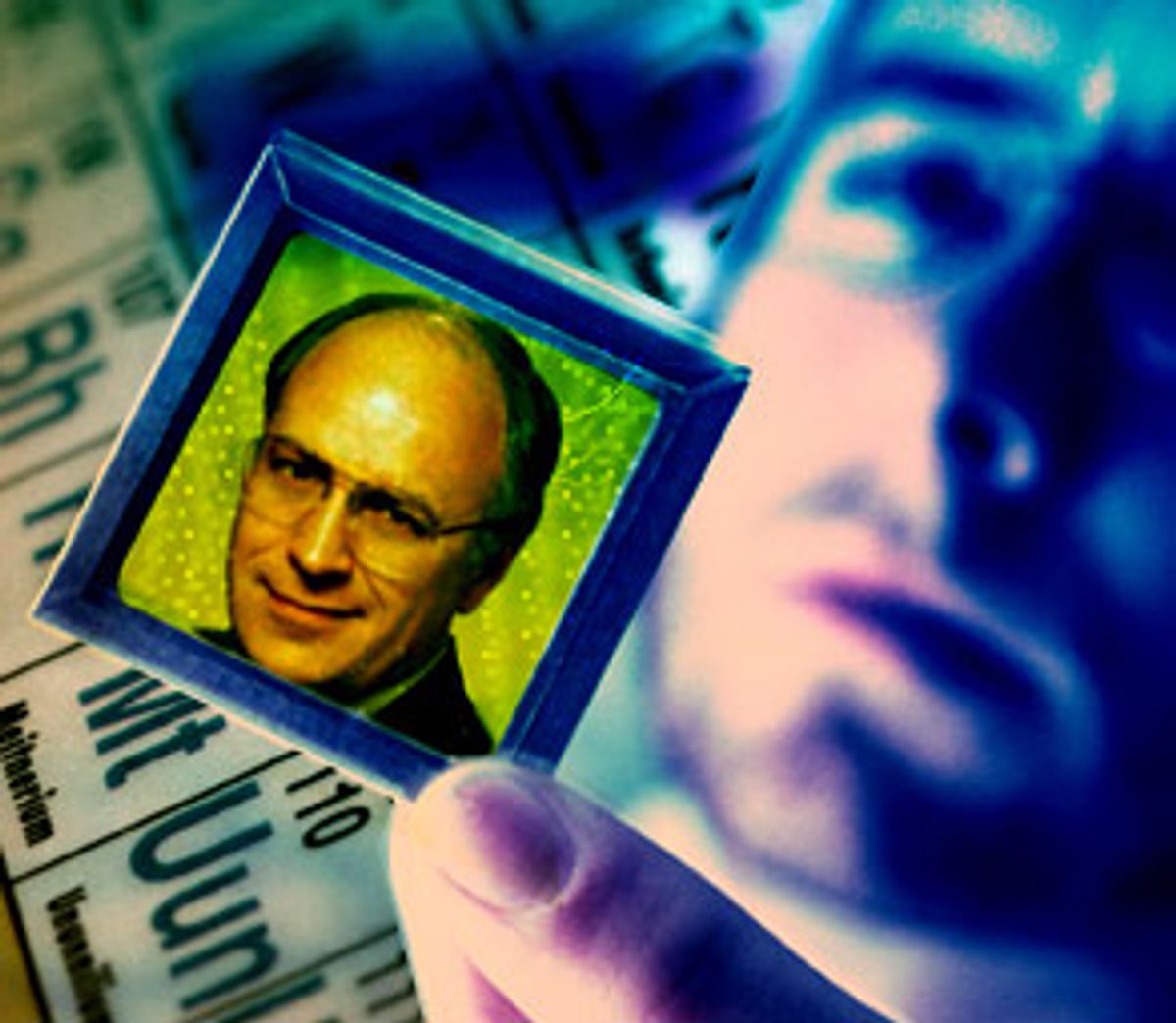

So when Dick Cheney was officially announced as George W. Bush's running mate this week, campaign managers went to great lengths to show that Cheney was physically fit. A highly credentialed cardiologist tapped by the Bush family gave the 59-year-old former defense secretary a clean bill of health -- despite a medical history that includes three previous heart attacks and quadruple bypass surgery more than a decade ago.

The basis for this medical pronouncement seems thin at best. Denton Cooley, chief surgeon at the Texas Heart Institute, based his assessment not on an actual examination of Cheney but on a review of his records and a telephone call to his cardiologist, Jonathan Reiner, whom Cooley reported as saying: "Mr. Cheney is in good health with normal cardiac function."

Reiner then gently countered that no one who has had three heart attacks has completely "normal" cardiac function -- that is, the three heart attacks had left Cheney with permanent damage to the heart.

So how sick is Cheney? It's confusing, as Wednesday's New York Times story on the subject attests. The lead cheerily announces that Cheney is in "excellent health," then goes on to state that he takes "many drugs for heart disease and other medical conditions." The laundry list that follows is pretty daunting: besides heart disease, the doctor had him treated for a number of other ailments (including many for which he continues to take medication), from gout to skin cancer to a potentially fatal allergic reaction to pomegranates to metabolic disorders.

Of course, it's quite possible that Cheney could be relatively unaffected by his past heart troubles. Certainly quantum leaps in the treatment of heart disease, the nation's No. 1 killer, have dramatically improved the quality of life of those diagnosed, even after surgery. A greater understanding of the disease and what signifies its recurrence also allows doctors to more closely monitor a person's condition.

Controlling the diet, regular exercise, quitting smoking and taking medication -- all things that Cheney practices, according to his doctor -- can change the lives of heart disease sufferers profoundly, doctors say.

"The perception is that people who suffer heart disease are not capable of fully functioning," says Dr. Lynn Smaha, a cardiologist and the past president of the American Heart Association. "But many people go on to live fully productive lives after surgery."

But campaigns are highly stressful affairs. Earlier this year, New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani was forced to drop out of a high-profile Senate race against first lady Hillary Clinton because of his fight with prostate cancer. And Bill Bradley, who unsuccessfully sought the Democratic presidential nomination, canceled several public appearances because of his irregular heartbeat, a much less serious condition than Cheney's heart troubles.

"Campaigns are kind of like the first year of law school or med school," says Kevin Sweeney, who served as press secretary for presidential hopeful Gary Hart's two attempts to win the presidency. "You are primarily motivated by a fear of failure. If you lose by a close margin, you can spend hours thinking 'If I had only made a few more phone calls, it might have made a difference.'"

Admittedly, top candidates don't go through the same rigors as their staff. "I was pulling an average of two all-nighters a week," says Sweeney. "Gary didn't do that. The top person works the least. He has to be fresh."

But back-to-back late night interviews and early morning shows, constant travel and the anxiety of participating in public debates and other functions can take their toll on a presidential candidate, Sweeney said.

Most doctors can't directly answer the question of how a presidential campaign might affect someone who has heart disease. They do point to other high-stress professions that have loosened their attitude toward heart disease sufferers in recent years: It used to be that airline pilots were permanently grounded at the first sign of heart problems, says Smaha. These days, as long as pilots pass various stress tests, some are allowed to fly again even after surgery.

"That's an interesting question," says Dr. Marc Gerdisch, a cardio-surgeon and spokesman of the American College of Cardiology. "It depends on the individual and how they deal with stress. Some stress is good stress. If you love what you are doing, it can be a motivator. If you hate it, that's a totally different kind of stress."

Regardless of how well Cheney deals with his stress, it's highly unlikely the public would hear about any serious health problems even if they did occur. Though it isn't always rational, human beings associate health inextricably with goodness and strength. The image a powerful leader must have is of good health.

Politicians and their handlers know this, and so political machines often go to great lengths both to bolster images of good health and to downplay illness in the public eye. Why else would Chinese President Jiang Zemin take a widely publicized dip in Hawaiian waters during his landmark 1997 tour of the U.S.? It was widely understood that his hour-long breast stroke was a symbolic attempt to silence rumors that the septuagenarian had heart disease and had experienced a heart attack on his U.S.-bound flight. Jiang's predecessors, Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, also performed well-timed public swims as a way of putting their physical health on display and to bolster various policy moves. At the onset of Mao's disastrous cultural revolution in 1966, for example, he swam against the tide in the Yangtze River.

Are such displays of athleticism just a quirk of the East? No way. When seeking the Democratic nomination for the presidency, Paul Tsongas employed the same technique to counter worries about his ailing health. Slick television spots showed him doing laps in a swimming pool.

Predictably, when the health of Mao and Deng began to fail, it took years for any official government pronouncements to acknowledge the facts. By the same token, when the Soviet Union's Boris Yeltsin began to exhibit enough erratic and unhealthy signs to fill a medical dictionary, the Kremlin constantly soft-pedaled the Russian leader's physical state. The aftermath of a heart attack he suffered during his successful 1996 reelection campaign was characterized simply as "colossal weariness" until he finally confessed to having undergone heart surgery.

Foreign leaders aren't the only ones with image-makers eager to gloss over their ill health. Let's not forget that the many signs that President Reagan's Alzheimer's was diagnosed while he was still in office, though he didn't announce it until 1994, long after his two terms were finished.

Is it better for the politician to fess up when feeling under the weather or maintain face for as long as possible? Given the relentless speculation that most candidates are subject to, it's not hard to understand why politicians will do whatever they can to maintain some vestige of medical privacy.

On the other hand, in our democracy, there's at least a presumption that the citizenry should be able to freely elect representatives whose bodies and minds can withstand the excruciating trials of public life. Besides, once there's even a hint of ill health, it becomes a matter of public debate and no amount of doctorly spin can prevent rumors from spreading.

Could George Bush have stemmed the tide of opinion in 1992 regardless of what information he released about his health? It's unlikely. And his son's new running mate, Cheney, may face a similar challenge.

The question is no longer will we see Dick run, but can he run? In answer to this question, don't be surprised if he suddenly is seen cheerfully jogging in a 10K race.

Shares