As an Internet project manager in telecommunications, I am familiar with the symbiotic business relationship of industry and government. I understand the dynamics of profit, getting new products to market as quickly as possible, negotiating "value-added" partnerships, and above all the potential for ethics to be sublimated to the bottom line.

As a mother, I didn't want to believe that the same business practices applied in medicine, because that would have meant accepting the possibility that my child was perceived first and foremost as a target market. A new mother is particularly vulnerable, and most of us harbor a trust bordering on reverence for the medical community, believing its members to be omniscient and above reproach.

When I held my baby in my arms for the first time and understood the magnitude of my responsibility, my faith in medicine translated into an implicit contract with my doctor: My job is to love him; your job is to keep him well.

And my baby was well, at least until 1998, when, at 2 years old, he was diagnosed with autism. When I read statistics from the Department of Education that said autism in school-age children had increased 556 percent in five years, skyrocketing past any other disability, I was shocked and horrified. But I trusted what my doctors told me: that the increase was due to better diagnostic skills, not to any real increase in autism.

It took two years for that trust to erode, chipped away by increasing evidence that business motives had mandated my child's health. I learned that congressional investigations were underway into key members of the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control who vote on U.S. immunization policy despite a web of conflicts of interest: panel members who owned stock in vaccine makers, received research grants from those companies or even owned vaccine patents themselves.

I found out that vaccines given to my child had unsafe amounts of mercury, contained in the preservative thimerosal: a fact that led to the introduction this year of new "thimerosal-free" vaccines. I learned that last year a rotavirus vaccine was rushed to market too soon, without enough research, and had to be suspended by federal health officials because children were experiencing life-threatening bowel obstructions.

But it was during a conference this June that I crossed over to the other side, from conventional mom to vaccine-reform advocate, and began sounding more and more like Mulder in "The X-Files," saying to anyone who would listen, "The truth is out there."

At an autism conference in Irvine, Calif., I heard the first theory that made sense to me intuitively, not just about autism but about other children who were sick, children I could see around me every day, children of my friends, the "typical" children who shared my son's classroom. Respected doctors and researchers presented evidence that the rise in autism over the past decade was related to immune system impairment, part of a spectrum of other childhood illnesses on the rise such as allergies, asthma, ADHD, learning disabilities and seizure disorders.

What was causing the immune system to turn against itself? The research was pointing to bombardment by multiple vaccines that overwhelmed the immature immune systems of infants and toddlers.

My son Connor was a perfect baby, the kind you see in commercials: engaging, happy, angelic. I had a normal delivery after a pitocin-and-epidural labor, and Connor scored a 9 on his Apgar, nursed vigorously, never had colic, smiled early and even laughed in his sleep at six weeks old. We figured we were doing everything right. When he got sick with his first ear infection at three months -- the first of many to come -- we did what most parents do: We relied completely on his doctor for treatment.

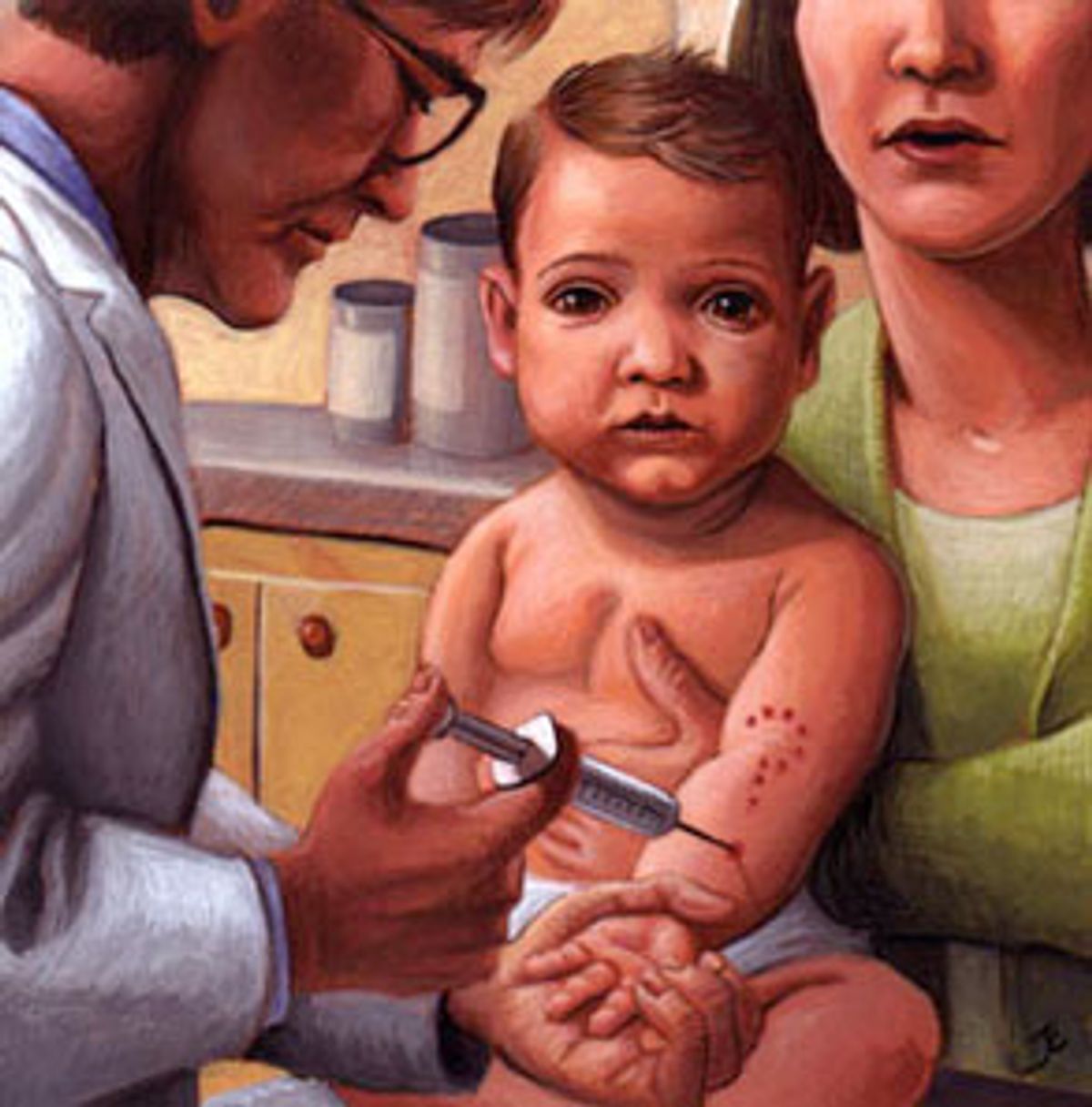

The American Academy of Pediatrics cautions against vaccinating children who are sick. I didn't know this policy at the time, and apparently neither did anyone in the doctor's office, because I was never told about it. What I did know was that he was supposed to get 33 vaccines before he started school, many of them simultaneously. My refrigerator magnet "freebie" of the vaccination schedule, included along with my complimentary diaper bag and free formula from the hospital, showed that he would be receiving as many as eight vaccines at the same time: combined measles, mumps, rubella (MMR), combined diptheria, tetanus, pertussis (DPT), polio and haemophilus influenzae type B. It seemed like a lot at one time, but I was simply grateful that the combination vaccines meant he would have fewer overall injections.

The ear infection and vaccination pattern continued unabated during Connor's infancy and into his toddler months. His reactions to vaccines ranged from nothing to crankiness to occasional fevers. All of these reactions were considered normal, and all of them passed within a day. The ear infections became harder to treat over time, as if Connor's system was building up an immunity to the frequent antibiotics.

One day in June of 1998 I noticed that his left ear was pushed out from his head. I had no idea what it meant but I took him to the doctor. Despite being on antibiotics, his latest ear infection had progressed into mastoiditis and he was rushed to the emergency room to get tubes in his ears that same day. The ear infections ceased. But an illness remained with him that was far worse than we had ever anticipated.

Much of his first year had been a period of triumphs. I marked his skills in my dog-eared copy of "What To Expect Your First Year," noting with satisfaction that he was hitting all of his milestones early. I could see that he was a sharp kid, alert to the world around him, and I was proud of his precocious awareness. This ability to focus extended to people as well -- he was compassionate and gentle in his temperament, possessing an unusual insight into the moods of the people around him. I honestly believed he showed early gifts of self-awareness and sensitivity to others.

Around his first birthday everything began to change. Connor regressed in his social behavior and speech and seemed to lose ground on all of his milestones. We had trouble getting his attention. We would call his name over and over again and finally had to look him in the face to get a response. At his birthday party, he was more interested in his balloons, ribbons and boxes than his new toys or the people celebrating around him. He would play with his toys repetitively and in unusual ways, like flipping over his bubble lawn mower to spin the wheels or rolling objects down a ramp for 30 minutes straight. Family members commented jovially that he might be a physics or engineering prodigy, already testing objects to see how they performed.

But when his language started to deteriorate, we lost any hope for his Nobel Prize and wanted desperately for him just to act normal. At 22 months he was mute; instead of pointing or naming things, he would lead one of us by the hand and place it on the thing he wanted. He preferred to watch the same video of "Thomas the Tank Engine" all day long rather than play with us. When people came over to our house he was shy, more than shy -- he would run away and hide -- and if we forced him out he would throw his body to the ground and scream.

I could see that the core of his real personality was still there, but I could only bring it out in him when he was totally at ease, which meant without distractions or interruptions in his routine. Even his diet changed for the worse. He would only eat about five foods -- crackers, Cheerios, McDonald's French fries, chips and cookies.

Time to take Connor back to the doctor, I thought. He'll know. He'll confirm my mom's intuition that something is very wrong. But he didn't.

"He used to talk and now he's quit talking."

"Well, he's been sick from the ear infections. Have you considered having his hearing tested?"

"Yes, we thought of that. His hearing is normal. I'm also worried that he's only eating a few foods, and he's not getting any vegetables and fruits anymore."

The doctor laughed. "My kids are extremely picky, too. As long as his weight is OK -- looks like he's in the 80th percentile -- I wouldn't worry about it. Toddlers are very finicky. As long as he's getting a multivitamin he's getting everything he needs."

Meanwhile Connor is flapping his arms and spinning in circles. I watched for a while. "So he's OK?"

My doctor's forte was reassuring worried moms. "Of course. He's fine. Let's see him again in a month and make sure his weight is on target."

As it turned out we didn't see the doctor again for a few months. By that time Connor's day care staff had evaluated his development and determined that he was autistic.

Months earlier, when we hadn't suspected any problems, I had enrolled Connor part-time in a day care program that mixed typical kids and special needs kids. My mother was physically disabled, and I wanted Connor to grow up in an environment that didn't exclude the handicapped. As it turned out the decision was a blessing -- the staff therapists had seen plenty of autistic kids, unlike my doctor, who had never seen even one (and who admitted humbly, later, that he only got three days of education on autism in med school). But the day care staff was able to diagnose him earlier than many kids with the same condition, which was probably the key to Connor's eventual progress.

I remember very clearly my first reaction to the label of autism: "But my kid's not Rain Man." And he wasn't. When I started reading I found out the real statistics on autism, and they were scary. There was a new crop of kids who had what many called "acquired autism." Unlike Dustin Hoffman's character, the kids progressed normally until their second year and during that period lost any accumulated skills and socially retreated from people.

The late-onset kids made the current genetic theory suspect -- if the cause was inborn, the kids would never have gained ground in the first place. Plus, the rate of these kids was staggering: In 10 years the incidence of autism had increased from one child in 10,000 to one child in 500. No one was sure why.

So I continued to go to doctors -- immunologists to help me understand why Connor's mosquito bites took six weeks to heal; neurologists to explain why his IQ was so low it couldn't be measured; allergists to tell me why his cheeks and ears got red when he ate certain foods; gastroenterologists to relieve his constipation. Over and over again I was told that the outlook for autistic kids was grim, there was no treatment available for his symptoms, that perhaps I should consider putting him (and myself) on Prozac to help with his behavior.

Frustrated by the lack of sympathy and knowledge in the medical community, I networked with parents on the Internet and read as much as I could on my own. I decided to focus on cures instead of causes. Some parents had actually been able to "recover" their children with behavioral therapy, or ABA. This therapy used a one-on-one approach to teach autistic kids how to interact in the world, to talk, to socialize, to learn academic concepts, to regain the skills they had lost or never developed. We started within weeks of Connor's diagnosis. In my heart and in my prayers I asked for one thing: Please, please let him say "mama" to me again.

And, amazingly, he did progress. One of Connor's doctors, who had seen the results of the therapy with her own eyes, agreed to write a prescription for this treatment, and I sent it along with my claims to the medical insurer. The claim was denied because the therapy was considered "educational." We continued to spend around $2,000 every month on behavioral treatment anyway. It was the only thing that was working.

Within a year Connor began talking again, regaining his old words first: mama (Yes!), daddy, cookie, no. Then he had a cognitive leap when language finally seemed to "click," and he was off and running. He sought out adults and other children to talk to and play games with, caught up to age level in comprehension, bypassed his classmates in academics, and even developed a sense of humor (he renamed "Carnotaurs from Disney's "Dinosaur" movie to "Connor-taurs").

In March of this year he finally lost his autism label, after a year and a half (at 25 hours per week) of intensive ABA. His speech was still a year behind, but it was appropriate, and his therapists predicted that by the time he started first grade he would have the same basic skills as his peers. I breathed my first tentative sigh of relief -- he had a chance of living a normal life.

It was only then that I began to focus attention back to the cause of Connor's condition, and listened with interest to the congressional hearings on autism in April, spurred by Rep. Dan Burton (R-Ind.), chairman of the Committee on Government Reform. Burton had almost lost his granddaughter to anaphylactic shock after her DPT vaccination, and lost his grandson to autism within a week of the child's receiving 11 vaccines administered in a single office visit.

I read the media coverage, too, most of it from medical professionals who pitied Burton's situation, but tended to dismiss him with red herrings, "out-sensationalizing" Burton with claims that not vaccinating children would lead to outbreaks of life-threatening diseases. (A recent Newsweek story does this too, ending on the note: "Autism aside, the measles virus can kill.")

But Burton wasn't interested in eradicating the vaccine program, just in getting some answers about the rise in autism. He asked CDC representatives about their investigations of the Brick, N.J., township where the autism rate was dramatically higher even than the rising national average. He wondered aloud about California Department of Developmental Services statistics, now replicated in many states, that reported a 273 percent increase in autistic kids in the school districts.

Autism was an epidemic, Burton insisted to the CDC. What are you doing about it?

The vaccination issue had come up many times in online chats about autism, but I didn't think it applied to me. Unlike many autistic kids, Connor was not whisked away to the emergency room after his MMR (mumps, measles and rubella) vaccination for seizures; he didn't "turn" autistic within hours of his DPT. He had a few mild reactions, nothing more.

But I didn't discount the parents' claims: I knew these parents personally and respected their judgment. Many were doctors or research professionals themselves. The only thing that connected a lot of us was a common history of chronic infections, mainly ear infections, and consistent doses of antibiotics.

I decided to attend a conference on autism and learn more about the biological research.

Before I left I went through Connor's photo album. I did this soon after he was diagnosed, but perhaps I was too close to him and too ignorant of autism to recognize dramatic changes. This time, I saw it: Connor at 11 months, smiling for the camera, looking into his daddy's eyes, touching his mommy's hair. Connor on his first birthday, after his morning visit to the doctor's office and MMR vaccination, no longer looking at anyone, no longer smiling. And perhaps the most revealing picture: Connor walking on his toes, one of the most common behaviors in autism. Within a day he had changed.

The conference speakers presented the theory that autism was part of a spectrum of related immune disorders on the rise in children. The immune dysfunction in the body was triggered by reactions to multiple vaccines, either an ingredient in the vaccines themselves or the accumulated damage of multiple vaccines to the immune system. The body reacted by attacking its own cells, an "auto-immune" response, with reactions in the body ranging from mild allergies and behavioral changes to severe neurological damage such as autism and seizure disorders.

This evidence made a lot of sense to me because I was seeing these kids with my own eyes everyday -- friends of mine whose kids were prone to severe allergies, asthma, attention and learning problems, all with no family history. When I was growing up, there was always one kid in the classroom who was allergic to eggs, who had circles under his eyes and pale skin. I never saw an autistic kid at all. Now I look around and see sick kids everywhere.

Dr. Andy Wakefield's presentation was particularly compelling. A respected gastroenterologist at the Royal Free Hospital in London, he had been minding his own business studying inflammatory bowel disease and Crohn's disease when he encountered something very curious that he hadn't seen before. When he tested the growing number of autistic children who had come in with bowel problems, he noticed that their GI systems were damaged as if they'd been diseased for years.

Wakefield listened to parents about the late onset of symptoms, the similar stories of regression and the parents' belief that vaccine damage may have caused the problem. When he ran more tests on the children he found measles virus in their GI tracts, where it wasn't supposed to be. He published preliminary findings in a respected British medical journal, the Lancet, and immediately came under fire from colleagues in the U.S. and UK.

As I listened to the evidence Wakefield had gathered, I looked around at the other parents. There was no commonality among us -- we were of all races and ethnic backgrounds and geographically spread out. A few of us had a genetic history of autism or allergies but most of us didn't.

If you controlled for all of these factors, what common link was there? Controlling for genetics, allergy histories in families and environmental toxins from varied geography, there was only one candidate left that applied to all of us -- a mandated vaccine program. Industrialized countries like the U.S., the UK and Canada were experiencing this tremendous rise in autism and other neurological disorders. And these were the same countries where modern medicine flourished.

Interestingly, Japan didn't figure among the other countries' high increase, and had withdrawn the MMR in 1993 because of concerns about adverse reactions. I started to become uneasy.

"I'm going to ask everyone a question," said the conference host after Wakefield's talk. "How many of you here believe your children have been damaged by vaccines?"

Seventy-five percent of the attendees stood up and raised their hands. One woman a few rows behind me was crying, and I knew intuitively that her faith in the medical establishment had finally crumbled. Her suffering was genuine; she sobbed quietly. When I looked back, she was embarrassed, covering her face with her hand.

But I was moved by her anguish, her private suffering, and I relived for a moment my own struggles since Connor's diagnosis. The long nights of guilt I felt as a mother, constantly wondering what I had done wrong to give him autism; the long days of research to find a cure -- the doctors told me to put him in an institution, but I wasn't going to leave him; the countless doctor visits and tests Connor bravely endured without understanding why he was hurting or receiving little relief.

And finally -- unsurprisingly -- I was overwhelmed with rage. I felt it building within me and it was like nothing I'd experienced before. I knew very clearly at that moment that I had crossed over to the other side, that I was convinced my son was a cash cow for an industry that tested its products in production rather than the lab, motivated by $2 billion per year in profits, no different in its potential for corruption than any other industry.

There were no higher standards in medicine than in any other business -- the rule of caveat emptor applied to vaccines as surely as it applied to any other consumer product. I could not trust the FDA and the CDC to protect me from pharmaceutical companies that wanted to get their products to market with as little testing as possible and to promote the repeated use of their products in order to maintain their monopoly under the guise of the public good.

I don't have a medical degree, but I have learned how to be a thoughtful medical consumer. Connor's up for his mandated boosters next year. I know now that he can have a simple blood test of his antibody titers, which measures his antibodies and confirms that he has the protection he needs against disease. I had the blood test done and he's protected.

There's no medical exemption from these boosters in my state for "sufficient protection based on antibody titers," so I'll have to use a religious exemption instead. I've accepted that there is no binding contract between me and the agencies and companies that purport to protect my child. But my bond with Connor remains, my responsibility as his mother expanding to include advocacy -- even activism -- along with love.

Shares