On Nov. 6, 1982, Eddie Murphy debuted on the big screen in the unpublicized first sneak of "48 HRS.," in a theater an hour's drive south of Los Angeles. The audience applauded as soon as they saw him onscreen: He was wearing sunglasses, a prison cap and headphones, and moaning and shrieking his way through his own homeboy version of "Roxanne."

Along with everyone else, I felt a ripple of static jolt the auditorium. When Murphy shed his prison grays for a sleek Armani suit and began pulling a spunky brand of jive on hard-guy cop Nick Nolte, that ripple became a pulsing current. And about halfway through, during Murphy's triumphant scene -- shaking down the belligerent honchos at a redneck bar -- that current became an indoor lightning storm. Nolte, stalking thugs and throwing his weight around with the physical force of Steve McQueen and the comic blowziness of Wallace Beery, got a healthy share of cheers and laughs. But after the movie the talk was all Eddie Murphy. With the advent of "Nutty Professor II: The Klumps," which opened last weekend to more business than any previous Murphy movie, I went through my file on the actor/comedian and found the notes I took about him during the filming of "48 HRS." I realized again how phenomenal he was from the beginning -- and how often his talent has been misused since. "48 HRS." remains the only Murphy film I'd want to see a second time because it wasn't a drive-he-said star vehicle, but a solidly built movie.

After "48 HRS.," "Trading Places" and "Beverly Hills Cop" (itself almost a "48 HRS." spinoff), Murphy became one of the pivots of our superstar-centered film culture. Executives molded movies around him and catered to his whims. He dominated productions and either worked with weak directors or weakened strong ones. For a while he got by on his comic charisma alone, even in flimsy spectacles like "Coming to America" (1988). By the time he executive-produced, directed, wrote and starred in "Harlem Nights" (1989) -- he gave himself, in all, a half-dozen credits on that one -- he seemed all used up. Murphy's '90s movies were a roll call of disappointments and catastrophes, including "Another 48 HRS.," "Boomerang," "The Distinguished Gentleman," "Beverly Hills Cop III" and "Vampire in Brooklyn."

Then came his comeback with "The Nutty Professor" (1996). Murphy was funny as Professor Sherman Klump, who experiments on himself with a formula that isolates and alters fat genes. But the film was still a half-baked remake of Jerry Lewis' 1963 chef d'oeuvre. Its success was a tribute to Murphy's performance and to the public's desire to see him as a softer, gentler character than the sharpshooters and slicksters of his first decade and a half. Klump is a sensitive soul: His billowing fat makes him look slovenly, but inside he has arrested elegance. He isn't like the other hefty members of his family -- all enacted amusingly by Murphy -- who feel at home in their bulk.

But "The Nutty Professor" was structured as a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde farce -- and it foundered on the Hyde side. Klump swigged his fat-gene formula and turned into a slender, hopped-up Eddie Murphy: an arrogant opportunist named Buddy Love, who was little more than a walking hard-on, literally overdosing on testosterone. Love was obviously meant to be a parody of Murphy's usual screen image -- in the first "Nutty Professor," Murphy nearly broke the fourth wall when he screamed that he thought Buddy Love was the man people wanted him to be. But all Murphy did to mock himself was yell and laugh louder and louder, and lather on self-love with a turkey baster. "Nutty Professor II: The Klumps" features a frantic attempt to salvage Buddy Love as a viable antagonist: The film genetically splices him with a dog. As a comic inspiration, it's a mutt.

And, overall, the sequel is an out-of-control, elephantine showcase for Murphy's virtuosity: It's a Murphy, Murphy, Murphy, Murphy World. The actor again plays, not just Buddy Love and Sherman Klump, but Sherman's randy-like granny, his proud, combative dad, his perpetually cooing mom, and his bitter (but still supportive) brother. These other Klumps become supporting characters, not mere cameo players -- and that's why the film is such an undeniable crowd-pleaser. Watching the group scenes in three-minute bits on "Oprah" last week, I thought they were hilarious. But in the movie they suffer diminishing returns, because there's no rhythm to the filmmaking, no momentum to the plot and no build to the characterizations. Only as Sherman's doting mom does Murphy provide any emotional payoff.

One reason that "The Klumps" performs so spectacularly at the box office is that Murphy has figured out how to go PG-13 without losing his R audience. He forges an unholy hybrid of Richard Pryor's profanity and Bill Cosby's coziness. This formula has long had mass appeal. As George Orwell wrote in his famous essay on low-down comic postcards, "the stuck-out behind, dog and lamppost, baby's nappy type of joke" can stand for "the Sancho Panza view of life" -- "the voice of the belly protesting against the soul" -- as well as "the music-hall world where marriage is a dirty joke or a comic disaster." But in "Nutty Professor II: The Klumps," the weight and repetitiveness of the scatological slapstick and putdowns wear you out.

"The Klumps" is like one of Peter Sellers' late Clouseau movies: Although you can't deny the lead performer's brilliance, the movie is just a shaky prop. Early on in his career, Murphy said, "I'd be the first to admit I'm a very funny guy and last to admit I'm a genius." But when Oprah recently declared him a genius on her show, all he could respond with was, "God bless you."

Murphy may be a comic genius, but he's no genius as a filmmaker (cf. "Harlem Nights"). The myth of Murphy as a movie talent unto himself began with the reports circulating around "48 HRS." that he wrote all his lines and comported himself as if movie stardom were his birthright.

The only in-print adult biography of the comedian ("Eddie Murphy: The Life and Times of a Comedian on the Edge") contains numerous references to Murphy's improvisations and a single quote from Murphy thanking the film's director, Walter Hill, for his editorial "blue pencil." Well, I observed that production on and off for a couple of months, and what I saw was simply healthy moviemaking -- a creative filmmaker and his ensemble elaborating on a script.

When I first visited the set of "48 HRS." six months before its sneak, Nolte was alternately fiddling with a still photographer's camera (he would next enact a photojournalist in "Under Fire") and cracking up the crew with his Lee Marvin imitation. Murphy was more distant, listening to a Dazz Band tape on his Walkman while waiting for his shot, then sauntering across the street for one of downtown L.A.'s killer tacos. (Though the action supposedly took place in San Francisco, there were only three weeks of Bay Area location work.) Murphy later admitted that Nolte "big-brothered" him throughout the early days of shooting.

"Eddie has terrific acting ability and tremendous theatrical instincts," director Hill told me at the time, "but Eddie is also a very untrained actor. You don't close the gap between him and someone like Nick in one moment or one day or one night.

"But there's this thing about movies that's proved true for Eddie: You only have to get it right once. You do three takes, and if you get it right once, you're fine. So movies serve Eddie's talent very well, and Eddie's talent serves movies very well. All this may sound like a criticism of Eddie, but it's not meant to be. People have to realize, it's so hard to be good once.

"I mean, movies are such a grab-ass medium: You get 20 minutes to rehearse and then you shoot and what you get you have to live with forever. Eddie had trouble focusing, but he understood that right away. He's carrying a big load -- a lot of people are watching him very carefully to see how he'll do in his first movie. He's taking the chance to demonstrate dramatic abilities that he couldn't have shown walking through some comedy thing. I think Eddie has cracked beyond that right off the bat."

As the filming went on, Murphy's performance began to arouse a certain affectionate awe among his co-workers. On one steaming July day I watched Hill guide Murphy through a complicated nightclub scene. Murphy had to follow catcher-like hand signals to thread his way across the floor in sight of the camera, and when he reached the bar he had to proclaim, "My name is Reggie Hammond," as if that meant something to two women and the bartender. When Hill called for a retake, Murphy pulled himself up to his full height and stared his director down before asking, in a tone of mock-menace: "Are you challenging my comedic timing?" Hill chuckled and gave a palms-out gesture, as it to say, "Hey, I'm only your director." Later, co-writer Larry Gross compared Murphy to (of all people) Frank Sinatra: "They're both entertainers who can be funny and sexy and then surprise people with their strength."

When I met Murphy, I mentioned that we both came from the same hometown -- Roosevelt, N.Y. He looked at my white face in disbelief. I named the address I lived at in the '50s, the parochial school across the street, the elementary school down the block. He didn't want to acknowledge that the journalist in front of him shared his turf. All he would say is, "The neighborhood changed a lot since then."

Of course, in the mid-'60s the population of Roosevelt had gone from white to black with astonishing rapidity, and I didn't presume to know the ins and outs of that metamorphosis. (I moved away when I was 8.) Murphy did know, and wasn't letting on. He had emerged from black suburbia: a culture that first found expression (albeit of a debased sort) in TV sitcoms rather than movies, at a time when "urban action film" was (as it still is) a euphemism for "black shoot-'em-up."

What people responded to in Murphy from the start was his live-wire presence. He got a physical charge out of turning people on (and suffered more than most comics when he was only heard, on records). He specialized less in rage than in effrontery. Though he was applauded for "angry black humor," one of Murphy's major wellsprings was black self-satire. He got off on African-American tackiness. His hustler character, "Velvet Jones," peddled a book called "I Wanna Be a Ho." A convict character on "SNL" recited a poem called "Kill My Landlord" and blew his rebel-poet front by spelling Kill "C-I-L-L." The surface joke behind his militant black film critic, "Raheem Abdul Muhammad," was his anger that blaxploitation icons like Fred Williamson weren't taken seriously.

The deeper joke came from Murphy's own inability to keep a straight face when saying lines like, "What about Isaac Hayes in 'Truck Turner'? He made a contribution." In one way, Reggie Hammond was a role Murphy had been preparing for with nearly everything he'd done. To Murphy, there was never anything funnier than a style that misfits a man. The sex-starved, prison-rusty Reggie Hammond, dressed to lady-kill, was unable in the romantic clutch to arrive at a better erotic come-on than, "It's 10:05 -- by 10:10 I want to be into some serious flesh."

Murphy became a huge hit in "48 HRS." partly by playing a metropolitan thief, not a suburban wiseguy. Even if his best stand-up comic characters came straight out of Roosevelt (like gay hairdresser Dion), the persona that made him an instant superstar was pure urban fantasy.

But was that necessarily a bad thing? As Hill told me in '82, "We're asking a lot of Eddie, and it's really to his credit that he chose to put up with it. I mean, he could have done 'Meatballs III' or any of those other things that late-night comedians usually end up with. But he really has to act in this movie. It's got humor, but nothing hokey. It's a lot to ask a first-time movie actor, but we're asking it and we're getting it."

Murphy later confessed to me, "At first I was nervous, or at least a little out of it. I mean, literally, I'd been doing comedy on Saturday night and then had to do a prison scene Monday morning. Those prison scenes did scare me. Then I just realized I had to get back that 'fuck-it-Eddie' attitude." And he did. During the last weeks of shooting, Murphy was flying high on the release of a comedy album, appearances on "The Tonight Show" and the success he was already beginning to savor on "48 HRS."

"When I first started the movie," he said, "some people were being too nice to me -- they were saying, 'Oh, you're beautiful' when they were thinking 'Oh, you suck.' I know, because later we re-shot some of the shit. But I got more confident. Now I'm really confident. And next week I'll probably feel so confident I'll want to go back and shoot the whole movie over again.

"It wasn't hard to get into character; Reggie Hammond reminds me a lot of my older brother, Charlie, a badass dude. He's in the Navy now -- that's how slick he is. Staying in character was harder. Walter and Nick kept me from overdoing things."

I mentioned to Murphy that a few crew members were surprised that a nice suburban kid like him could be so scary. "Rage was the hardest emotion for me to carry through the movie," he admitted. "I'd have to be crazy to feel that kind of anger. I have had a real damn nice life. I have no rage in me. An acting teacher, David Proval [who this year wowed audiences as the ticking-bomb Richie Aprile in "The Sopranos"], had to teach me how to express Reggie's anger. He taught me how to use the little things that irritate me to get me really angry."

Since Murphy's portrayals of black lowlifes brought him criticism even when performed as flat-out comedy on "SNL," you might think he'd have been reluctant to start his movie career playing a felon. But he bristled at any suggestion that Reggie Hammond is a demeaning figure: "I think this is the first time that you'll see a black character like him in a movie. He will be articulate and snazzy and hip and smart. He's funny -- he doesn't just go around saying, 'You jive turkey,' or 'You white motherfucker.' He's not a crook -- he's a thief. There's a difference. He chooses to do what he does. And he's a good con man. There's nothing demeaning about him."

Murphy credited Hill's open-mindedness for allowing his character to grow. "There was none of that producer's attitude -- you know what I mean, some old guy telling me [for this Murphy assumed a New York-nasal accent], 'Whaddaya mean you people don't say these things, a' course you say these things.'" Murphy knew his credibility was on the line. "What did scare me is that movies are what I want to end up doing. I thought that if I fucked up I'd be on TV the rest of my life."

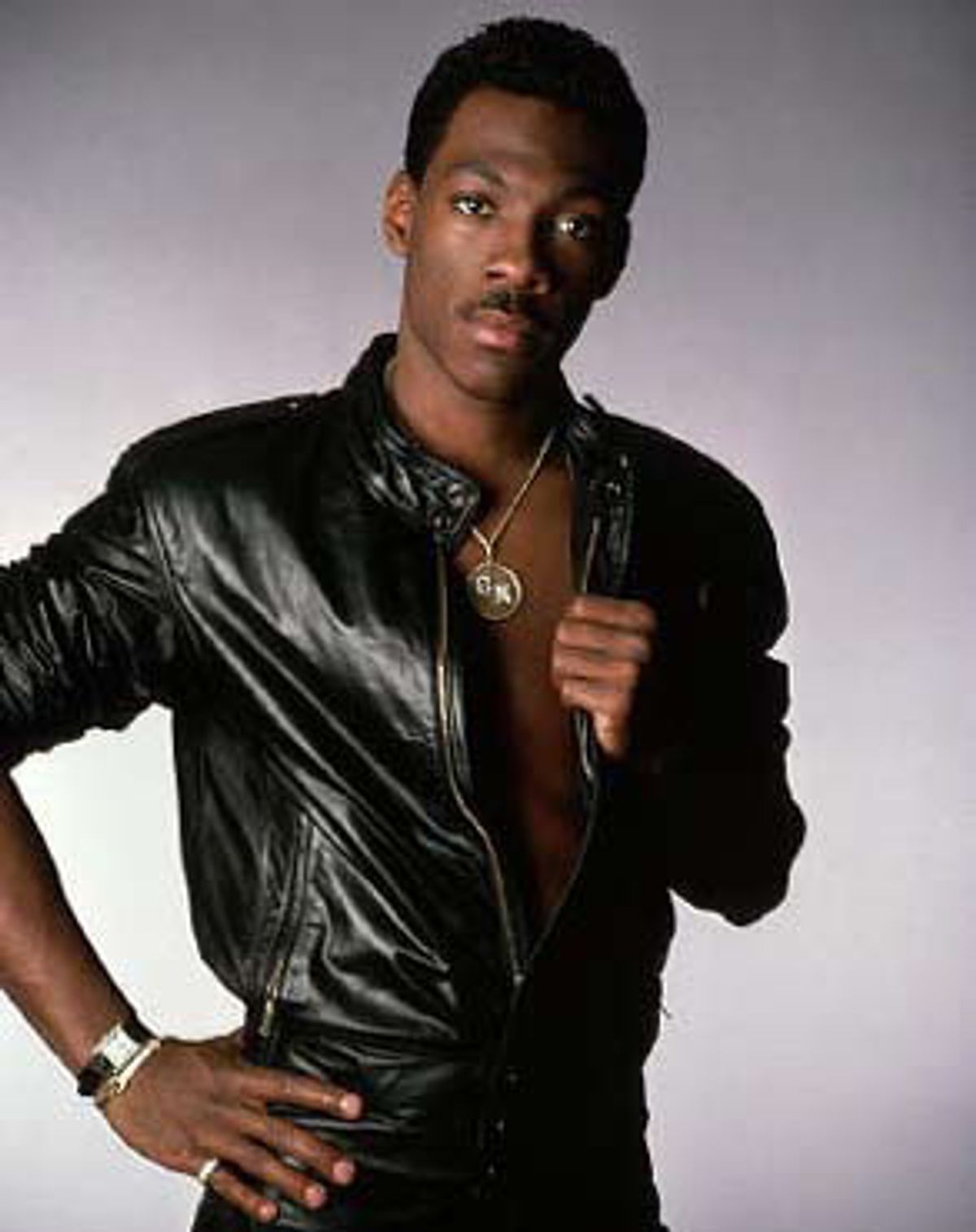

But after just two TV seasons and one movie, Murphy managed to turn his industrial-strength sass into a devastating comedy-delivery package. No one before or since -- including Murphy -- has so deftly communicated a visceral giddiness at being young, gifted, black and beautiful.

In his "Klump" movies, Murphy attempts to bring the same zing to characters drawn from his suburban-family roots. But he's trying to do it with directors like Tom Shadyac (the first "Nutty") and Peter Segal ("Nutty II") whose scrappy timing and go-for-the-guffaw desperation reduce even the juiciest material to a series of skits.

Whatever one thought of last year's "Bowfinger," Murphy, in his dual supporting parts, showed a rare willingness to submerge his talent in Steve Martin's comic vision. In the Klumps he's all over the place in more ways than one. Without the collaboration of directors with blue pencils to prune the potty jokes and purple shenanigans, Murphy may find that the public will weary of his earthy family-man act more swiftly than it did his slick bachelor with a badge.

Shares